The farmer-distiller was a familiar figure in the 19th Century state of Maryland. These were canny individuals with working farms who determined that the “value added” of turning their corn, wheat and rye into alcohol rather than selling to the local grain merchants made good sense. With good roads and ready markets in Washington and Baltimore, they founded distilleries and whiskey brands that often bore their names. Notable among them was Melky Miller, shown here driving a sleigh.

Melky was born in 1833, christened either “Melchior” or “Melchoir” Mueller -- his baptismal certificate gives the first spelling and his tombstone the second.

The farmer-distiller was a familiar figure in the 19th Century state of Maryland. These were canny individuals with working farms who determined that the “value added” of turning their corn, wheat and rye into alcohol rather than selling to the local grain merchants made good sense. With good roads and ready markets in Washington and Baltimore, they founded distilleries and whiskey brands that often bore their names. Notable among them was Melky Miller, shown here driving a sleigh.

Melky was born in 1833, christened either “Melchior” or “Melchoir” Mueller -- his baptismal certificate gives the first spelling and his tombstone the second.  In 1838 his family moved to what is now Garrett County, Maryland, then part of Allegheny County, and settled in a town with the highly improbable name of Accident. Located near Deep Creek Lake in the northern county, the town can trace its unusual name, according to historians, to the mid-1700s when two independent groups of surveyors each identified it as prime land and an a subsequent owner wished to commemorate the happy “accident.” Its downtown is shown here in the early 1900s.

In 1838 his family moved to what is now Garrett County, Maryland, then part of Allegheny County, and settled in a town with the highly improbable name of Accident. Located near Deep Creek Lake in the northern county, the town can trace its unusual name, according to historians, to the mid-1700s when two independent groups of surveyors each identified it as prime land and an a subsequent owner wished to commemorate the happy “accident.” Its downtown is shown here in the early 1900s. The Muellers were industrious people and good farmers. They prospered in Accident. It is not clear when Melky anglicized his name to Miller; the practice was a common one particularly for German immigrants seeking to assimilate into American society. Little is known about Melky’s early life. As an adult, he married a woman named Barbara, eight years his junior, and together they raised a family, including three sons.

Melky might have gone through life unremarked had he not bought a farm in 1875 along a tributary of South Branch Bear Creek, just southeast of Accident. He was 42. According to a family history, he also bought a small distillery owned by Joel Miller in the Cove area of Garrett County and moved the equipment to his farm.

Melky possessed sufficient wealth from farming to afford the investment in whiskey production. He himself knew little about distilling. A canny entrepreneur, Melky initially hired professionals to operate the business. His three sons -- William, John, and Charles -- learned the art of making whiskey from these hirelings and in time replaced them.

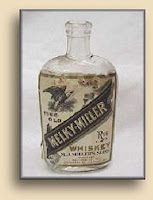

The firm also was noted for the artistic design of both the jugs and the bottles in which it marketed its products. It also featured giveaways like shot glasses and corkscrews. Melky’s name was prominently displayed on all whiskey labels and merchandising items.

In 1902 Melchior sold the distillery to his sons. Reflecting the new owners, the company changed its name to M.J. Millers Sons Distillery. William continued as distiller, while John and Charles established wholesale and retail whiskey businesses in nearby Westernport, Maryland. The firm also warehoused its products in that town.

The firm also was noted for the artistic design of both the jugs and the bottles in which it marketed its products. It also featured giveaways like shot glasses and corkscrews. Melky’s name was prominently displayed on all whiskey labels and merchandising items.

In 1902 Melchior sold the distillery to his sons. Reflecting the new owners, the company changed its name to M.J. Millers Sons Distillery. William continued as distiller, while John and Charles established wholesale and retail whiskey businesses in nearby Westernport, Maryland. The firm also warehoused its products in that town. His boys had an evident genius for business and soon built Melky Miller’s Maryland Rye Whiskey into a highly respected local and regional brand. Although production was relatively small -- only 29 bushels of grain processed daily according to Federal records -- the quality of the company’s whiskey was high. For example, Melky’s product adhered to the Federal “bottled-in-bond” requirements.

Barbara Miller died in 1913 when she was 72, two years before Melky passed away in 1915 at the age of 82. They are buried in the cemetery next to Zion Lutheran Church in Accident. Their sons continued to operate the distillery until 1919 when Prohibition closed their doors, never to reopen.

In 1920 all bonded whiskey in the Accident warehouses was transferred to a Federal facility in Cumberland. The distillery itself was closed and left to decay.

In Accident the foundations for the bonded warehouses of the distillery can still be seen 200 feet south of Miller Road, a quarter mile east of the Brethren Church Road intersection. The abandoned structures reportedly were destroyed by fire in 1971. The Garrett County Historical Society has erected a sign memorializing the site. In effect, the “National Accident” called Prohibition had come to Accident, Maryland.

In 1920 all bonded whiskey in the Accident warehouses was transferred to a Federal facility in Cumberland. The distillery itself was closed and left to decay.

In Accident the foundations for the bonded warehouses of the distillery can still be seen 200 feet south of Miller Road, a quarter mile east of the Brethren Church Road intersection. The abandoned structures reportedly were destroyed by fire in 1971. The Garrett County Historical Society has erected a sign memorializing the site. In effect, the “National Accident” called Prohibition had come to Accident, Maryland.

_.jpg)

.jpg)