William L. Perkins was an Easterner, born in Oxford, New York, in 1929 and raised in New York City. At the age of 20 he decided that “The Big Apple” was not a place to make his fortune. Instead he headed for California and the Gold Rush in 1849, taking the perilous trip “sailing before the mast,” as one biographer put it, around South America and north to to San Francisco. Although there is no evidence of his striking gold, Perkins stayed in California for 21 years, likely working in the mercantile trades.

William L. Perkins was an Easterner, born in Oxford, New York, in 1929 and raised in New York City. At the age of 20 he decided that “The Big Apple” was not a place to make his fortune. Instead he headed for California and the Gold Rush in 1849, taking the perilous trip “sailing before the mast,” as one biographer put it, around South America and north to to San Francisco. Although there is no evidence of his striking gold, Perkins stayed in California for 21 years, likely working in the mercantile trades. It was in California that Perkins met Sarah Peabody. They married in 1859 and their union produced three children, Mabel V., William L. and Lena A. Meanwhile, Sarah’s brother, George Peabody, with a partner named Maurice Lyons, had established a small liquor store in St, Paul, Minnesota. Peabody, Lyons & Co.

It was in California that Perkins met Sarah Peabody. They married in 1859 and their union produced three children, Mabel V., William L. and Lena A. Meanwhile, Sarah’s brother, George Peabody, with a partner named Maurice Lyons, had established a small liquor store in St, Paul, Minnesota. Peabody, Lyons & Co. was lightly capitalized at the outset and located in a small (20 by 40 feet) two-story stone building on St. Paul’s Third Street. As the business met with success the quarters were expanded by adding another forty feet.

In 1872, likely because of the declining health of Sarah, the Perkins family pulled up stakes in California and moved to St. Paul. This time they were able to make the trip by train. By that time the first transcontinental railroad had been built across the western half of America and onto the East. The lines stretched 1,776 miles. Their route took the Perkins family to Chicago and then north to Minnesota. Although the trip took more than a week, it was much shorter than the 100-plus days required for sailing "round the Horn."

Once in St. Paul Perkins bought out Peabody’s interest in the liquor dealership and became part of the management. He proved to have a flair for the whiskey trade and his contacts in California apparently provided an advantage with that state’s wine and brandy makers. Operating now as Perkins, Lyons & Co., the business continued to flourish. Needing more room and a better address, the partners moved to 319 Robert Street, about the year 1900. It is the St. Paul thoroughfare shown above. This store occupied a much larger building, one 25 by 150 feet and four stories tall.

According to a contemporary publication the new quarters allowed the partners to keep “as compete and full stock as can be found in any city in the West.” The account continued: "Messrs. Perkins, Lyons and Company carry from fifteen hundred to three thousand barrels in bond, of different ages, all for the purpose of keeping their stock in St. Paul always up to the standard. The firm of Perkins, Lyons and company keep all the time three salesmen on the road, and port of the time four, who visit pretty much every town in northern Wisconsin, Minnesota and Dakota territory, monthly; their sales amounting to from $250,000 to $300,000 yearly, requiring a capital of about $100,000, now, to do the business, thus showing quite an increase in this particular line of business during the last twenty years in St. Paul."

About 1886, Maurice Lyons bowed out of the firm, selling his interest to Perkins. The change in management was reflected in a change of name. The enterprise subsequently became known as W. L.

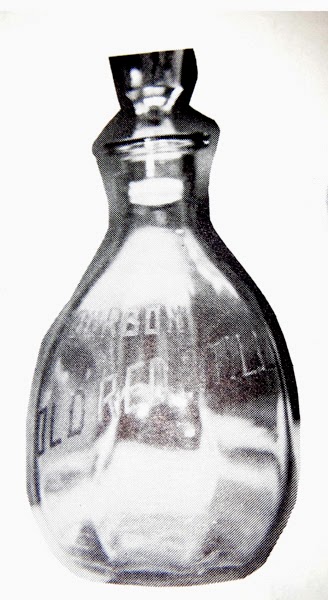

Perkins & Co. The firm’s flagship brand was “Old Red Still,” as shown here with its characteristic red and black label. Perkins provided his customers with a variety of bottle shapes and sizes for Old Red Still, including back of the bar bottles. Another major Perkins brand was “Non-Pareil.” He registered the name in 1907

Perkins & Co. The firm’s flagship brand was “Old Red Still,” as shown here with its characteristic red and black label. Perkins provided his customers with a variety of bottle shapes and sizes for Old Red Still, including back of the bar bottles. Another major Perkins brand was “Non-Pareil.” He registered the name in 1907 and was allowed its use, even though the brand earlier had been registered by a New York company. He also issued a back of the back decanter for Non-Pareil Whiskey, as well as the five cent token shown below.

and was allowed its use, even though the brand earlier had been registered by a New York company. He also issued a back of the back decanter for Non-Pareil Whiskey, as well as the five cent token shown below.My personal favorite among Perkins’ glassware is a small decanter with a bulbous base and flaring mouth. It was made expressly for use on passenger trains. As shown here, it bore a paper collar that said “Made Expressly for the Dining Car Service of.....By W. L.

Perkins & Co, St. Paul, Minn.” A blank was left in the middle of the label for the railroad to add its name or logo. My assumption is that it held a quantity of whiskey or wine.

Perkins & Co, St. Paul, Minn.” A blank was left in the middle of the label for the railroad to add its name or logo. My assumption is that it held a quantity of whiskey or wine.As William L. Perkins, Jr., reached maturity, his father brought him into the firm. Junior had been born in San Francisco but had achieved his education in the Midwest, boarding at the Shattuck Military School in Faribault, Minnesota, and later attending Griswold College in Davenport, Iowa, both institutions affiliated with the Episcopal Church. Junior finished his education about 1887 and went to work for his father learning the whiskey trade. Upon the boy reaching the age of 23 and showing promise as a businessman, Perkins in 1991 made him a full partner. With his future assured, the son shortly after got married in St. Paul to

Leocaldio Ryan. (Her first name in Spanish means “numerology.”)

Leocaldio Ryan. (Her first name in Spanish means “numerology.”)Father and son continued to expand their business during the 1900s. A 1907 publication reported that they now were marketing their liquor over a wide territory in the Northwest and employed seven traveling salesmen who were constantly on the road. Their mercantile staff had similarly expanded to

twenty-two employees working at the Robert Street facility and at a branch office in Minneapolis. The Perkins firm boasted it had been designated as the Northwestern agents for Old Crow and one of five national representatives of the John Gibson line of whiskeys.

twenty-two employees working at the Robert Street facility and at a branch office in Minneapolis. The Perkins firm boasted it had been designated as the Northwestern agents for Old Crow and one of five national representatives of the John Gibson line of whiskeys.Father and son Perkins also were gaining attention for their civic and social activities. Both were members of Masonic orders, identified as Republicans (though said to be voting independent in local elections) and active Episcopalians. In addition Junior was a member of the St. Paul Lodge No. 59 of the Elks, the Commercial Club and the Jobbers Union. These whiskey men had, as one author put it, “gained place prominent among the representative merchants and wholesale dealers of Minnesota.”

Along the way the family knew sorrow. Sarah Peabody Perkins, wife and mother, died about 1892. The effort to find a more healthful climate for her in the clear air of Minnesota had failed and her condition gradually had deteriorated. Although mourning her loss, her survivors continued to operate their wholesale liquor business. In St. Paul directories William was listed president and treasurer, Junior as corporate secretary. In 1919 with business curtailed as a result of the advent of National

Prohibition, the W. L. Perkins Company moved to 339 E. Seventh Street, its final address. It closed shortly after, never to reopen.

Prohibition, the W. L. Perkins Company moved to 339 E. Seventh Street, its final address. It closed shortly after, never to reopen.Note: Two principal sources provided the information for this vignette on William Perkins and his family: 1) THE BOOK OF MINNESOTANS; a Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men of the State of Minnesota. 1907. By: Albert N. Marquis, and 2) A History of Ramsey County and the City of St. Paul, 1826-1917, by George E. Warner. That the Perkinses figured in both is additional testimony to the reputation father and son had achieved, finding gold, not in California, but in Minnesota. Three bottle illustrations are from the Ron Feldhaus book, Bottles, Breweriana and Advertising Jugs of Minnesota, 1850-1920.

.