J. P. Haddox, who put his picture on the “label under glass” pocket flask at left was a leading liquor dealer in Winchester, Virginia. With a reputation as a successful businessman and civic leader, he was elected chair of the Democratic Party in his home town and the captain — head man —of a local volunteer fire company. About 1898, however, Haddox decided to invest in a brewery and within a decade his economic house came crashing down despite a testimonial to his beer that involved a singing frog.

A native son of Winchester, Haddox was born in 1853 into a family of longtime Virginians. Throughout his life he seems to have been known by multiple names. Written out in full it was John Perry Haddox, but other versions in public records identified him variously as John P. Haddox, J. Perry Haddox and J.P. Haddox. We can assume that he received his education in the elementary and perhaps secondary schools of Winchester. About 1874, at the age of 22 he married a local girl, Annie E. Buckley and began a family.

Haddox appears to have been well established in his liquor business by the 1890s, ran a retail

establishment called the Moon One Price Cash Clothing Store on Main Street, and was moving up the social/political ranks of Winchester. His election as captain of the Friendship Fire Company not only meant recognition of his ability and enthusiasm as a firefighter but carried a great deal of social prestige. He became Grand Master of the local chapter of Old Fellows. Moreover, like many Southern whiskey men his political views were “wet” and Democratic Party oriented. Elected chair of the Winchester Democrats, Haddox was wheeling and dealing in local and state politics. A 1899 news article reported him heavily involved in organizing a convention in Winchester to select Senatorial candidates.

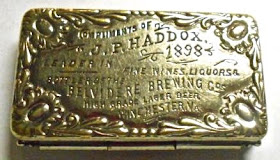

Symbols of his prosperity in the liquor trade were the quality of his give-away items to special customers. Although his advertising corkscrew could be had for pennies, the picture flask shown above and a second label under glass giveaway of a winsome lass both were pricey items. Note too the silver plated match safe, shown below. It bears the inscription, “Compliments of J. P. Haddox, leader in fine wines, liquors and bottler of the Belvidere Brewing Co.’s high grade lager beer.” The silver-plated safe, sometimes called a “vesta,” is dated 1898 and would have been relatively expensive to produce.

Symbols of his prosperity in the liquor trade were the quality of his give-away items to special customers. Although his advertising corkscrew could be had for pennies, the picture flask shown above and a second label under glass giveaway of a winsome lass both were pricey items. Note too the silver plated match safe, shown below. It bears the inscription, “Compliments of J. P. Haddox, leader in fine wines, liquors and bottler of the Belvidere Brewing Co.’s high grade lager beer.” The silver-plated safe, sometimes called a “vesta,” is dated 1898 and would have been relatively expensive to produce. That was the fateful year that Haddox expanded from selling whiskey into making beer. A bottling factory for carbonated beverages had begun in the 1880s in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, a 30 mile drive over the Blue Ridge Mountains from Winchester. At the outset the company was a very small operation, occupying only a single building and employing only a few workers, most of them said to be poorly paid. With the decision of the local owners to expand into brewing beer in the mid-1890s, the facilities were expanded considerably, resulting in considerable debt. When the brewery failed to be profitable, bankruptcy loomed.

That was the fateful year that Haddox expanded from selling whiskey into making beer. A bottling factory for carbonated beverages had begun in the 1880s in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, a 30 mile drive over the Blue Ridge Mountains from Winchester. At the outset the company was a very small operation, occupying only a single building and employing only a few workers, most of them said to be poorly paid. With the decision of the local owners to expand into brewing beer in the mid-1890s, the facilities were expanded considerably, resulting in considerable debt. When the brewery failed to be profitable, bankruptcy loomed. Obviously sensing an opportunity, in 1898 Haddox and two Winchester brothers named Savage purchased the brewery property for a bargain basement $4,000 and began to make a beer they called “Belvidere,” a name they registered with the Federal Patent and Trademark office. As shown here they packaged their brew in both clear and amber bottles, some with porcelain closures. In addition to paper labels their bottles were embossed with the name of the company.

Obviously sensing an opportunity, in 1898 Haddox and two Winchester brothers named Savage purchased the brewery property for a bargain basement $4,000 and began to make a beer they called “Belvidere,” a name they registered with the Federal Patent and Trademark office. As shown here they packaged their brew in both clear and amber bottles, some with porcelain closures. In addition to paper labels their bottles were embossed with the name of the company.

Enter the singing frog. As shown left, one of the brewery’s customers in Harrisonburg, Virginia, named W. H. Willis, the manager of the Kernstown Showroom a local saloon, took out an ad in the Harrisonburg paper to extoll the virtues of Belvidere Beer. Terming the beer “delightful” and claiming no hurt could come from it, he proclaimed: “But if even a frog drinks it, it will make him sing — for joy!” Mr. Willis apparently knew something about frogs to elicit this glowing testimonial.

Haddox and his partners, after buying the Harpers Ferry property, spent lavishly on refurbishing the brewery and re-building a customer base — both expensive. Before long it became clear to them that the Belvidere Brewery was continuing to be a losing proposition and that nothing could be done to remedy the situation. In 1907 the partners decided to sell the brewery buildings and property. How much was realized in the sale were not disclosed but indications are that losses were involved.

The economic drain of the brewery may well to have brought down Haddox’s Winchester clothing business. The 1908 photograph shown here tells the story: “J. P. Haddox store to be sold without reserve…to retire from business.” Haddox’s entire stock, pegged at worth $20,000, was to be disposed of and the store had been put into the hands of a New York salvage firm.

Earlier Haddox had suffered another painful blow. Annie, his wife and the mother of their five children died at the young age of 44 in January 1899. She was buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Winchester with this inscription on her tomb: “In after time we’ll meet her. Her children will rise up and call her blessed. We love her.” The family heartbreak was echoed a year later when Haddox, his occupation given as “liquor dealer,” was listed as a 47 year old widower. He subsequently was remarried to Mariam V. Redmond, a woman who had a daughter by an earlier marriage when they wed.

Only 55 years old when he announced retirement from business, Haddox in subsequent years faded from public records. He was out of the liquor business when Virginia went “dry” in 1916 and lived long enough to witness one daughter, Mary Agnes, die in 1933. Three years later, in July 1936, John Perry Haddox himself died, age 83. Another daughter, Edmonia, would pass away the same year. Haddox lies in a crypt next to wife Annie in Mt. Hebron Cemetery, Winchester. A chain of three links decorates his plaque. His inscription is from a poem by Nancy Priest Wakefield (1838-1915): “I shall know the loved who have gone before; And joyfully sweet will the meeting be; When over the river, the peaceful river; The Angel of Death will carry me.” Strangely, the plaque omits Haddox’ date of death.

Note: Since I first profiled J. P. Haddox several weeks ago, I was contacted by Brenda Creech,

a descendant of that gentleman, to point out where a correction was needed and who subsequently provided other information that I have added. She also gave permission to add the image of Haddox's label under glass flask showing a pretty girl, an item owned by another family member. I am grateful to them for their help.