Patrick J. Dempsey, shown here, was known in Lowell, Massachusetts, as one of its most benevolent citizens, contributing to a host of charities out of his considerable wealth from whiskey sales. As one Lowell commentor put it: “His obituary reads like the cause for canonization of a saint.” Nonetheless his liquor store became the centerpiece of an 1870 melee, during which police were assaulted and shots were fired. The event became known as the Lowell “Rum Riots.”

Patrick J. Dempsey, shown here, was known in Lowell, Massachusetts, as one of its most benevolent citizens, contributing to a host of charities out of his considerable wealth from whiskey sales. As one Lowell commentor put it: “His obituary reads like the cause for canonization of a saint.” Nonetheless his liquor store became the centerpiece of an 1870 melee, during which police were assaulted and shots were fired. The event became known as the Lowell “Rum Riots.”

Born on St. Patrick’s Day in 1822 in Rathban, County Wicklow, Ireland, a village tucked in the Wicklow Mountains, shown above, Dempsey was the son of Christopher and Katherine Dempsey. Of his early life and education, little is known. By the late 1840’s he had arrived in the United States, eventually finding his way to Lowell where many Irish immigrants had settled.

By 1848 at age 27 Patrick found a bride in Bridget C. Hill, a 20-year-old local girl. Over the next decade the couple would have three daughters. Family responsibilities may have provided him the incentive to strike out on his own. He rented a basement room where he brewed root beer. According to “LowellIrish,” a Lowell historical site, Dempsey was so successful he branched out into beer and other alcoholic products. That led to his running saloons and opening a series of bars and liquor stores, reputedly “dealing spirits across the state.”

But Dempsey faced a challenge in a rising prohibitionary tide. Next door, Maine as early as the 1850 had passed laws against the consumption of alcohol. The campaign accelerated after the Civil War as returning veterans swelled the drinking public. During the 1870s Massachusetts joined other New England states in cracking down on liquor sales. When authorities came to Lowell, they immediately headed to Dempsey’s establishment, the city’s largest, shown above. An outraged and rowdy opposition crowd gathered.

LowellIrish [see below] told the “rum riot” story: “The crowds began stoning the officers. One of the roughians used a hoe to strike an officer. The officer’s gun fired during the melee hitting one of the crowd. The man who struck the officer, Pender, was arrested and held for bail, but his case was quickly moved since his family was known to have small pox. The next day the crowd returned, but was informed of undercover constables in the crowd who were ready to stop any trouble before it erupted.”

When that crowd dispersed, the Lowell melee effectively ended. The following day, as the authorities returned ready to do battle, they were greeted by pro-“dry”

When that crowd dispersed, the Lowell melee effectively ended. The following day, as the authorities returned ready to do battle, they were greeted by pro-“dry”

women and girls cheering them on. Dempsey’s stock was among the hundreds of barrels of alcohol seized and shipped to Boston for disposal. As frequently happened, the crackdown was followed by strong public backlash. Dempsey soon was back in business, advertising his “ales, wines and liquors of all sorts.”

That included sales of one of the most controversial alcoholic beverages of the times: Absinthe, thought to be highly addictive. Widely known as “the green fairy,” Dempsey’s absinthe sold under a green butterfly label, one of the few brands marketed in America outside of New Orleans. The product gained considerable public attention. Shown below is a spoof of a Van Gogh painting showing Vincent, sitting at a bar, sketching. A bottle of Dempsey’s “Butterfly Absinthe” sits at his elbow.

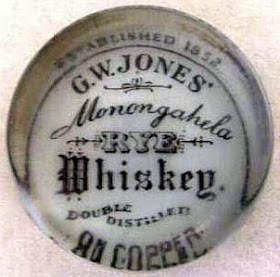

Whiskey brands featured by the Irishman’s liquor house included: “Caprice,” “Mayfair,” “Miami,” “Milady,” “Overmarch,” "Patts Malt,” "Puritan Gin,” “Tournament,” and “Westover." The company waited until 1906 after trademark laws were strengthened to register most of those brands with federal authorities. “Patt’s Malt Whiskey,” which I assume was named after the founder, interestingly was not among them.

Whiskey brands featured by the Irishman’s liquor house included: “Caprice,” “Mayfair,” “Miami,” “Milady,” “Overmarch,” "Patts Malt,” "Puritan Gin,” “Tournament,” and “Westover." The company waited until 1906 after trademark laws were strengthened to register most of those brands with federal authorities. “Patt’s Malt Whiskey,” which I assume was named after the founder, interestingly was not among them.

Leavening Dempsey’s business successes were the heartaches in his personal life. After ten years of marriage his wife Bridget died, leaving him with three small daughters to raise. Four years later, he remarried. His bride was Margaret Deehan, a Lowell woman of 24. Over the next thirteen years the couple would have seven children of their own. The first was George Christopher, an only son, and six more girls. In 1865, daughter Catherine, only 15, would die. In total Dempsey would witness the deaths of three daughters before his own passing.

None of those losses, however, dimmed Dempsey’s innate benevolence. Recognizing his status as one of richest men in Lowell, he was a regular contributor to a number of causes. A favored one was St. John’s Hospital, shown here, where he was accounted a founder and continuous benefactor. His gifts to St. John’s were said to have included “preserves, sugar and a child’s bathtub.” Dempsey was also known for sending floral displays to the funerals of friends, neighbors and employees.

None of those losses, however, dimmed Dempsey’s innate benevolence. Recognizing his status as one of richest men in Lowell, he was a regular contributor to a number of causes. A favored one was St. John’s Hospital, shown here, where he was accounted a founder and continuous benefactor. His gifts to St. John’s were said to have included “preserves, sugar and a child’s bathtub.” Dempsey was also known for sending floral displays to the funerals of friends, neighbors and employees.

Despite his wealth Dempsey chose to reside in a Lowell district known as “The Acre.” in effect an Irish “ghetto.” In time he was able to buy considerable real estate there, living in a house large enough to contain his growing family. It became the centerpiece of a tract known as “Dempsey’s Place,” with surrounding

apartment buildings that he owned and typically rented to Irish immigrants. Although rich enough to have lived in upscale parts of Lowell, his preference was to reside among his fellow countrymen. Dempsey also bought property in Salem, Massachusetts, on the Atlantic shore north of Boston where the family had a summer home.

After the brief prohibitionary setback of 1870, Dempsey continued to guide the fortunes of his beverage empire for the next three decades. He carefully groomed George as his successor, seeing that the young man graduated from high school with sufficient credentials to be admitted to MIT. There George, shown here, was given special training in chemistry as a member of the class of 1888. Upon his graduation, the father admitted him as a partner in his enterprises. Dempsey’s wisdom soon became apparent as George demonstrated an exceptional affinity for the liquor trade.

After the brief prohibitionary setback of 1870, Dempsey continued to guide the fortunes of his beverage empire for the next three decades. He carefully groomed George as his successor, seeing that the young man graduated from high school with sufficient credentials to be admitted to MIT. There George, shown here, was given special training in chemistry as a member of the class of 1888. Upon his graduation, the father admitted him as a partner in his enterprises. Dempsey’s wisdom soon became apparent as George demonstrated an exceptional affinity for the liquor trade.

The father-son partnership terminated in 1901 when Patrick’s health faltered and George took on full management responsibilities. In December of the following year Patrick Dempsey died. After a well-attended funeral Mass, he was buried in St. Patrick Cemetery in Lowell. The drawing here graced the “whiskey man’s” obituary.

The father-son partnership terminated in 1901 when Patrick’s health faltered and George took on full management responsibilities. In December of the following year Patrick Dempsey died. After a well-attended funeral Mass, he was buried in St. Patrick Cemetery in Lowell. The drawing here graced the “whiskey man’s” obituary.

Upon taking over the operation George Dempsey made immediate changes. He took steps to create a new partnership with Lowell resident Patrick Keyes. He also began the process of trademarking company-issued brands of whiskey. He moved the corporate headquarters to Boston, the building shown below, and incorporated it as “P. Dempsey & Company.” By 1913, George had built his own distillery in Boston and was no longer dependent on outside suppliers.

George also was gaining a national reputation as an anti-Prohibition activist While Patrick was described as a quiet man of few words, his son gained attention as an active spokesman for National Association of Distillers and Wholesale Dealers. “When the liquor controversy arose in 1906, Mr. Dempsey appeared before the Secretary of Agriculture to represent the intelligent thought from the liquor dealers’ side, and won high praise from Secretary [James] Wilson.” — said his obituary. George also published a book, “The Prohibition Question” in which he excoriated the “drys” for “…making officers of the law double-faced and mercenary, legislators timid and insincere, candidates for office hypocritical and truckling….”

If he had lived, Patrick would have been proud of his son’s fight on behalf of the whiskey trade. In the end George’s eloquence made no difference. On January 1, 1920 National Prohibition was imposed. The liquor empire that Patrick Dempsey had spent his life building came to an abrupt end after almost 70 years in business.

Note: This post would not have been possible without the information provided by the article from LowellIrish of March 29, 2012. The organization included this statement: “The mission of LowellIrish is to collect and preserve the history and cultural materials, which document the presence of the Irish community in Lowell. As the first immigrant group in a city that continues to celebrate its immigrant past, LowellIrish will serve as an advocate to support a better understanding of the historical, political, religious, and social function the Irish played in the formation of the city.”

Addendum: With the current post this website has registered a milestone 1.4 million "hits" over its 12 years of existence, with interest in pre-Prohibition American whiskey history coming from all over the world. I am very grateful for this response and hope to continue posting articles for the foreseeable future.

%20Bldg.jpg-%20C.jpg)

%20copy.jpg-%20C.jpg)

%20copy.jpg-%20C.jpg)

%20%20copy.jpg-%20C.jpg)

.jpg-%20C.jpg)