Foreword: The story of the Samuels distilling family stretches from before the American Revolution until the present day, representing eight generations. Given the length and importance of the Samuels’ story, it is related here in two installments. The first part, below, traces Samuels distilling from its beginnings, to the Revolutionary War, through the Civil War and ends just before the turn of the 20th Century. Part Two follows in six days.

The story of the Samuels family begins with John Samuels Senior, a clergyman for the Church of Scotland, living in the village of Samuelston outside of Edinburgh. After moving to Northern Ireland to preach, a decade later John Senior sailed on an early shipload of Scotch-Irish settlers coming to the American colonies. He settled in Pennsylvania. Little is known of his son, John Samuels Junior but almost certainly he was a farmer/distiller. In his will that Samuels left a still to his son Robert Samuels. Again, little is known of Robert. He is recorded as a farmer/distiller, making rye whiskey in East Pennsboro Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. When he died, his 30 gallon still was passed on to his son, Robert Samuels Junior.

Born in 1755, Robert Junior was a Pennsylvania volunteer in the Revolutionary War, cited as having supplied whiskey for the troops. That he was distilling spirits seems indisputable, but there are at least two accounts of the war story. One version has Robert making whiskey for himself and sharing it with his fellow soldiers. A second version brings George Washington into the narrative.

Washington, as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, famously is quoted in his daily orders of August 7, 1776, decreeing that every soldier should have a daily ration of liquor “as an encouragement to them to behave well and to attend diligently to their duty.” Although the ration amounted to only four ounces of spirits a day, the order was highly popular with the troops. As the story goes, Washington commissioned Robert Junior to leave off other duties and concentrate full time making whiskey. He complied.

Successful at providing the much-desired spirits, Robert was honorably discharged from the Army following the end of the Revolutionary War. Returning to his home in Pennsylvania, he found that two brothers had claimed 60 acres of land for him near Bardstown in the then Kentucky region of Virginia under the Virginia’s Corn and Cabbage Patch Act of 1775. Robert soon moved his family to his new homestead. With him went a 60 gallon still. A member of a local militia, he served several seasons as an officer when not engaged on his farm growing corn and making whiskey. Thus began the Kentucky heritage of the Samuels family.

Successful at providing the much-desired spirits, Robert was honorably discharged from the Army following the end of the Revolutionary War. Returning to his home in Pennsylvania, he found that two brothers had claimed 60 acres of land for him near Bardstown in the then Kentucky region of Virginia under the Virginia’s Corn and Cabbage Patch Act of 1775. Robert soon moved his family to his new homestead. With him went a 60 gallon still. A member of a local militia, he served several seasons as an officer when not engaged on his farm growing corn and making whiskey. Thus began the Kentucky heritage of the Samuels family.

Robert’s son, John Samuels carried on the family tradition of distilling. As his father had discovered, although Kentucky had rich soil for growing grain, rye was not an entirely successful crop and corn was. John understood that his mash of corn worked equally well and that turning it into whiskey was an efficient way to transport the grain harvest and at the same time add value. About 1820, John built his family the stately looking Georgian home below. It became a gathering place for subsequent generations of the Samuels distilling clan.

In the early days of the Samuels distilling dynasty, the most prominent member of the family was John’s nephew, Taylor Williams Samuels, known as “T. W.” His claim to fame, however, went beyond distilling to becoming the lawman credited with the surrender of the Jesse and Frank James, cited by some as a final act of the American Civil War.

In the early days of the Samuels distilling dynasty, the most prominent member of the family was John’s nephew, Taylor Williams Samuels, known as “T. W.” His claim to fame, however, went beyond distilling to becoming the lawman credited with the surrender of the Jesse and Frank James, cited by some as a final act of the American Civil War.

The story goes this way: As the Civil War was drawing to a close, a number of Confederate raiders, freed from the restriction of military control, roamed the Upper Midwest, pillaging and murdering the local populations. Among them were future outlaws Jesse and Frank James, shown left. With their compatriots surrendering all around them, the James boys decided their best, perhaps only, option was to surrender and headed to Nelson County, Kentucky, and Bardstown, a city they knew well.

The story goes this way: As the Civil War was drawing to a close, a number of Confederate raiders, freed from the restriction of military control, roamed the Upper Midwest, pillaging and murdering the local populations. Among them were future outlaws Jesse and Frank James, shown left. With their compatriots surrendering all around them, the James boys decided their best, perhaps only, option was to surrender and headed to Nelson County, Kentucky, and Bardstown, a city they knew well.

They were the sons of a Bardstown woman, known as the Widow Zerelda Sims, who earlier had been married to Robert James and the mother of his children. At the time the James boys arrived in town T. W. Samuels was High Sheriff of Nelson County and well known to them both. Mother Zerelda now was remarried to the sheriff’s brother, Ruben Samuels. Related by marriage, Sheriff Samuels wanted nothing to do with the brothers and urged Ruben to get them to leave.

Instead, their surrender was arranged. Jesse and Frank on July 4, 1865, met with Sheriff Samuels on the front porch of his general store and gave him their guns. Shown here, Frank’s weapon, a 1851 Colt revolver, can be viewed in a Bardstown museum. In retrospect, since this event came months after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, some consider this act as officially ending the Civil War. The James brothers rode out of Kentucky free men to begin their lives as outlaws and enter the annals of Western history.

Instead, their surrender was arranged. Jesse and Frank on July 4, 1865, met with Sheriff Samuels on the front porch of his general store and gave him their guns. Shown here, Frank’s weapon, a 1851 Colt revolver, can be viewed in a Bardstown museum. In retrospect, since this event came months after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, some consider this act as officially ending the Civil War. The James brothers rode out of Kentucky free men to begin their lives as outlaws and enter the annals of Western history.

Meanwhile T. W. was establishing himself as the first in the line of Samuels distillers to own and manage a true commercial operation. Beginning In 1844, and later working with his son, William Isaac Samuels, know as “W.I.”, T. W. Samuels undertook to move beyond his ancestors and build a large scale distillery. The site was a land grant estimated at 4,000 acres, nine and one half miles northwest of Bardstown. Near the village of Deatsville, the plant was constructed was adjacent to a small station on the Bardstown and Springfield Branch of the L&N Railroad. Shown below, by 1886 the Samuels distillery was mashing an estimated 100 bushels a day, yielding 14 barrels of whiskey. It had two bonded warehouses with a storage capacity for 9,500 barrels.

The Samuels, operating as T. W. Samuels & Son Company, over a period of almost a half century continuously ramped up production. By 1890, they were mashing grain for 110 barrels daily. Insurance underwriter records noted that the distillery was of frame construction with a metal or slate roof. The property included two bonded warehouses, both iron-clad with metal or slate roofs. One warehouse was located 220 feet north of the still. A second one was nearby. The property also contained a “free” warehouse, not subject to federal supervision, in an old frame building. The Samuels also maintained a small loading and unloading depot on the rail line.

With corn for mashing readily available, good transportation for getting their whiskey to markets throughout the Ohio Valley and beyond, and a reputation for making good whiskey, business boomed. The father and son sold their whiskey under the brand name “T.W. Samuels Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey.” Over the decades, as shown here, the labels were varied from time to time. Throughout his life, T. W. was considered by his fellow Kentucky distillers as a strong-willed, sometimes contentious, personality. In short, a person not to be trifled with. According to 1860 federal records, before the Civil War T. W. Samuels owned five slaves: males, ages 38, 22 and 9; females, ages 19 ad 8.

Ironically, after the long years of the Deatsville distillery, a decision was made to personify a “gentler and kinder” T.W Samuels in company advertising. An artist’s image portrayed him as “the Ole” T. W., a goateed Southern gentleman with almost no resemblance to the original. This likeness was published in newspapers, featured on billboards, and added to the whiskey label, as shown on the image that opens this vignette. The distillery registered its first trademark in 1905, one that included the faux T. W. Samuels.

Ironically, after the long years of the Deatsville distillery, a decision was made to personify a “gentler and kinder” T.W Samuels in company advertising. An artist’s image portrayed him as “the Ole” T. W., a goateed Southern gentleman with almost no resemblance to the original. This likeness was published in newspapers, featured on billboards, and added to the whiskey label, as shown on the image that opens this vignette. The distillery registered its first trademark in 1905, one that included the faux T. W. Samuels.

During more some four decades, W. I. Samuels worked at the distillery alongside his often domineering father. Thoroughly schooled in the art and science of making good whiskey, the adult W. I. gained a local reputation as a successful cattle breeder and for his civic work in Nelson County, including founding a school. More genial than his father, he became friends with members of the Beam family and popular with other local distillers.

When T. W. Samuels died in January, 1898 at the age of 77, cause not described, he was buried in the New Salem Baptist Church Cemetery in Nelson County. His memorial monument is shown below. The inscription reads: “How desolate our home bereft of thee.”

After waiting years to succeed his father, W. I. Samuels immediately took over management of the Deatsville Distillery. For decades he had worked there alongside his often domineering father. W. I.’s health was faltering, however, and only five months after his father’s death, in July 1898 he succumbed at age 52. W. I. was buried in the Bardstown City Cemetery, elsewhere from his father’s grave.

Now the mantle of Samuels whiskey making fell on W. I.’s son, Leslie Samuels, a change that ushered in a whole new chapter in the family’s whiskey saga. That story is the subject of my next post.

Note: A great deal of information about the generations of the Samuels distilling family can found on the Internet. This post is drawn from myriad sources. It is a matter of sorting out the details and trying to create a coherent narrative.

.

Samuels Family Distilling — Origins to Today, Part 1

Foreword: The story of the Samuels distilling family stretches from before the American Revolution until the present day, representing eight generations. Given the length and importance of the Samuels’ story, it is related here in two installments. The first part, below, traces Samuels distilling from its beginnings, to the Revolutionary War, through the Civil War and ends just before the turn of the 20th Century. The second part follows in four days.

The story of the Samuels family begins with John Samuels Senior, a clergyman for the Church of Scotland, living in the village of Samuelston outside of Edinburgh. After moving to Northern Ireland to preach, a decade later John Senior sailed on an early shipload of Scotch-Irish settlers coming to the American colonies. He settled in Pennsylvania. Little is known of his son, John Samuels Junior but almost certainly he was a farmer/distiller. In his will that Samuels left

a still to his son Robert Samuels. Again, little is known of Robert. He is recorded as a farmer/distiller, making rye whiskey in East Pennsboro Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. When he died, his 30 gallon still was passed on to his son, Robert Samuels Junior.

Born in 1755, Robert Junior was a Pennsylvania volunteer in the Revolutionary War, cited as having supplied whiskey for the troops. That he was distilling spirits seems indisputable, but there are at least two accounts of the war story. One version has Robert making whiskey for himself and sharing it with his fellow soldiers. A second version brings George Washington into the narrative.

Washington, as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, famously is quoted in his daily orders of August 7, 1776, decreeing that every soldier should have a daily ration of liquor “as an encouragement to them to behave well and to attend diligently to their duty.” Although the ration amounted to only four ounces of spirits a day, the order was highly popular with the troops. As the story goes, Washington commissioned Robert Junior to leave off other duties and concentrate full time making whiskey. He complied.

Successful at providing the much-desired spirits, Robert was honorably discharged from the Army following the end of the Revolutionary War. Returning to his home in Pennsylvania, he found that two brothers had claimed 60 acres of land for him near Bardstown in the then Kentucky region of Virginia under the Virginia’s Corn and Cabbage Patch Act of 1775. Robert soon moved his family to his new homestead. With him went a 60 gallon still. A member of a local militia, he served several seasons as an officer when not engaged on his farm growing corn and making whiskey. Thus began the Kentucky heritage of the Samuels family.

Robert’s son, John Samuels carried on the family tradition of distilling. As his father had discovered, although Kentucky had rich soil for growing grain, rye was not an entirely successful crop and corn was. John understood that his mash of corn worked equally well and that turning it into whiskey was an efficient way to transport the grain harvest and at the same time add value. About 1820, John built his family the stately looking Georgian home below. It became a gathering place for subsequent generations of the Samuels distilling clan. As seen right, today the house is a boutique hotel redolent with whiskey history.

In the early days of the Samuels distilling dynasty, the most prominent member of the family was John’s nephew, Taylor Williams Samuels, known as “T. W.” His claim to fame, however, went beyond distilling to becoming the lawman credited with the surrender of the Jesse and Frank James, cited by some as a final act of the American Civil War.

The story goes this way: As the Civil War was drawing to a close, a number of Confederate raiders, freed from the restriction of military control, roamed the Upper Midwest, pillaging and murdering the local populations. Among them were

future outlaws Jesse and Frank James. With their compatriots surrendering all around them, the James boys decided their best, perhaps only, option was to surrender and headed to Nelson County, Kentucky, and Bardstown, a city they knew well.

They were the sons of a Bardstown woman, known as the Widow Zerelda Sims, who earlier had been married to Robert James and the mother of his children. At the time the James boys arrived in town T. W. Samuels was High Sheriff of Nelson County and well known to them both. Mother Zerelda now was remarried to the sheriff’s brother, Ruben Samuels. Related by marriage, Sheriff Samuels wanted nothing to do with the brothers and urged Ruben to get them to leave.

Instead, their surrender was arranged. Jesse and Frank on July 4, 1865, met with Sheriff Samuels on the front porch of his general store and gave him their guns. Shown here, Frank’s weapon, a 1851 Colt revolver, can be viewed in a Bardstown museum. In retrospect, since this event came months after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, some consider this act as officially ending the Civil War. The James brothers rode out of Kentucky free men to begin their lives as outlaws and enter the annals of Western history.

Meanwhile T. W. was establishing himself as the first in the line of Samuels distillers to own and manage a true commercial operation. Beginning In 1844, and later working with his son, William Isaac Samuels, know as “W.I.”, T. W. Samuels undertook to move beyond his ancestors and build a large scale distillery. The site was a land grant estimated at 4,000 acres, nine and one half miles northwest of Bardstown. Near the village of Deatsville, the plant was constructed near a small station on the Bardstown and Springfield Branch of the L&N Railroad. Shown below, by 1886 the Samuels distillery was mashing an estimated 100 bushels a day, yielding 14 barrels of whiskey. It had two bonded warehouses with a storage capacity for 9,500 barrels.

The Samuels, operating as T. W. Samuels & Son Company, over a period of almost a half century continuously ramped up production. By 1890, they were mashing grain for 110 barrels daily. Insurance underwriter records noted that the distillery was of frame construction with a metal or slate roof. The property included two bonded warehouses, both iron-clad with metal or slate roofs. One warehouse was located 220 feet north of the still. A second one was nearby. The property also contained a “free” warehouse, not subject to federal supervision, in an old frame building. The Samuels also maintained a small loading and unloading depot on the rail line.

With corn for mashing readily available, good transportation for getting their whiskey to markets throughout the Ohio Valley and beyond, and a reputation for making good whiskey, business boomed. The father and son sold their whiskey under the brand name “T.W. Samuels Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey.” Over the decades, as shown here, the labels were varied from time to time. The

Throughout his life, T. W. was considered by his fellow Kentucky distillers as a strong-willed, sometimes contentious, personality. In short, a person not to be trifled with. According to 1860 federal records, before the Civil War T. W. Samuels owned five slaves: males, ages 38, 22 and 9; females, ages 19 ad 8.

Ironically, after the long years of the Deatsville distillery, a decision was made to personify a “gentler and kinder” T.W Samuels in company advertising. An artist’s image portrayed him as “the Ole” T. W., a goateed Southern gentleman with almost no resemblance to the original. This likeness was published in newspapers, featured on billboards, and added to the whiskey label, as shown on the image that opens this vignette. The distillery registered its first trademark in 1905, one that included the faux T. W. Samuels.

During more some four decades, W. I. Samuels worked at the distillery alongside his often domineering father. Thoroughly schooled in the art and science of making good whiskey, the adult W. I. gained a local reputation as a successful cattle breeder and for his civic work in Nelson County, including founding a school. More genial than his father, he became friends with members of the Beam family and popular with other local distillers.

When T. W. Samuels died in January, 1898 at the age of 77, cause not described, he was buried in the New Salem Baptist Church Cemetery in Nelson County. His memorial monument is shown below. The inscription reads: “How desolate our home bereft of thee.”

After waiting years to succeed his father, W. I. Samuels immediately took over management of the Deatsville Distillery. For decades he had worked there alongside his often domineering father. W. I.’s health was faltering, however, and only five months after his father’s death, in July 1898 he succumbed at age 52. W. I. was buried in the Bardstown City Cemetery, elsewhere from his father’s grave.

Now the mantle of Samuels whiskey making fell on W. I.’s son, Leslie Samuels, a change that ushered in a whole new chapter in the family’s whiskey saga. That story is the subject of my next post.

Note: A great deal of information about the generations of the Samuels distilling family can found on the Internet. This post is drawn from myriad sources. It is a matter of sorting out the details and trying to create a coherent narrative.

Labels: The Samuels family distilling, Robert Samuels jr., John Samuels, T. W. Samuels. W. I. Samuels, T.W. Samuels Kentucky Bourbon, Jesse James, Frank James

Samuels Family Distilling — Origins to Today, Part 1

Foreword: The story of the Samuels distilling family stretches from before the American Revolution until the present day, representing eight generations. Given the length and importance of the Samuels’ story, it is related here in two installments. The first part, below, traces Samuels distilling from its beginnings, to the Revolutionary War, through the Civil War and ends just before the turn of the 20th Century. The second part follows in four days.

The story of the Samuels family begins with John Samuels Senior, a clergyman for the Church of Scotland, living in the village of Samuelston outside of Edinburgh. After moving to Northern Ireland to preach, a decade later John Senior sailed on an early shipload of Scotch-Irish settlers coming to the American colonies. He settled in Pennsylvania. Little is known of his son, John Samuels Junior but almost certainly he was a farmer/distiller. In his will that Samuels left

a still to his son Robert Samuels. Again, little is known of Robert. He is recorded as a farmer/distiller, making rye whiskey in East Pennsboro Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. When he died, his 30 gallon still was passed on to his son, Robert Samuels Junior.

Born in 1755, Robert Junior was a Pennsylvania volunteer in the Revolutionary War, cited as having supplied whiskey for the troops. That he was distilling spirits seems indisputable, but there are at least two accounts of the war story. One version has Robert making whiskey for himself and sharing it with his fellow soldiers. A second version brings George Washington into the narrative.

Washington, as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, famously is quoted in his daily orders of August 7, 1776, decreeing that every soldier should have a daily ration of liquor “as an encouragement to them to behave well and to attend diligently to their duty.” Although the ration amounted to only four ounces of spirits a day, the order was highly popular with the troops. As the story goes, Washington commissioned Robert Junior to leave off other duties and concentrate full time making whiskey. He complied.

Successful at providing the much-desired spirits, Robert was honorably discharged from the Army following the end of the Revolutionary War. Returning to his home in Pennsylvania, he found that two brothers had claimed 60 acres of land for him near Bardstown in the then Kentucky region of Virginia under the Virginia’s Corn and Cabbage Patch Act of 1775. Robert soon moved his family to his new homestead. With him went a 60 gallon still. A member of a local militia, he served several seasons as an officer when not engaged on his farm growing corn and making whiskey. Thus began the Kentucky heritage of the Samuels family.

Robert’s son, John Samuels carried on the family tradition of distilling. As his father had discovered, although Kentucky had rich soil for growing grain, rye was not an entirely successful crop and corn was. John understood that his mash of corn worked equally well and that turning it into whiskey was an efficient way to transport the grain harvest and at the same time add value. About 1820, John built his family the stately looking Georgian home below. It became a gathering place for subsequent generations of the Samuels distilling clan. As seen right, today the house is a boutique hotel redolent with whiskey history.

In the early days of the Samuels distilling dynasty, the most prominent member of the family was John’s nephew, Taylor Williams Samuels, known as “T. W.” His claim to fame, however, went beyond distilling to becoming the lawman credited with the surrender of the Jesse and Frank James, cited by some as a final act of the American Civil War.

The story goes this way: As the Civil War was drawing to a close, a number of Confederate raiders, freed from the restriction of military control, roamed the Upper Midwest, pillaging and murdering the local populations. Among them were

future outlaws Jesse and Frank James. With their compatriots surrendering all around them, the James boys decided their best, perhaps only, option was to surrender and headed to Nelson County, Kentucky, and Bardstown, a city they knew well.

They were the sons of a Bardstown woman, known as the Widow Zerelda Sims, who earlier had been married to Robert James and the mother of his children. At the time the James boys arrived in town T. W. Samuels was High Sheriff of Nelson County and well known to them both. Mother Zerelda now was remarried to the sheriff’s brother, Ruben Samuels. Related by marriage, Sheriff Samuels wanted nothing to do with the brothers and urged Ruben to get them to leave.

Instead, their surrender was arranged. Jesse and Frank on July 4, 1865, met with Sheriff Samuels on the front porch of his general store and gave him their guns. Shown here, Frank’s weapon, a 1851 Colt revolver, can be viewed in a Bardstown museum. In retrospect, since this event came months after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, some consider this act as officially ending the Civil War. The James brothers rode out of Kentucky free men to begin their lives as outlaws and enter the annals of Western history.

Meanwhile T. W. was establishing himself as the first in the line of Samuels distillers to own and manage a true commercial operation. Beginning In 1844, and later working with his son, William Isaac Samuels, know as “W.I.”, T. W. Samuels undertook to move beyond his ancestors and build a large scale distillery. The site was a land grant estimated at 4,000 acres, nine and one half miles northwest of Bardstown. Near the village of Deatsville, the plant was constructed near a small station on the Bardstown and Springfield Branch of the L&N Railroad. Shown below, by 1886 the Samuels distillery was mashing an estimated 100 bushels a day, yielding 14 barrels of whiskey. It had two bonded warehouses with a storage capacity for 9,500 barrels.

The Samuels, operating as T. W. Samuels & Son Company, over a period of almost a half century continuously ramped up production. By 1890, they were mashing grain for 110 barrels daily. Insurance underwriter records noted that the distillery was of frame construction with a metal or slate roof. The property included two bonded warehouses, both iron-clad with metal or slate roofs. One warehouse was located 220 feet north of the still. A second one was nearby. The property also contained a “free” warehouse, not subject to federal supervision, in an old frame building. The Samuels also maintained a small loading and unloading depot on the rail line.

With corn for mashing readily available, good transportation for getting their whiskey to markets throughout the Ohio Valley and beyond, and a reputation for making good whiskey, business boomed. The father and son sold their whiskey under the brand name “T.W. Samuels Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey.” Over the decades, as shown here, the labels were varied from time to time. The

Throughout his life, T. W. was considered by his fellow Kentucky distillers as a strong-willed, sometimes contentious, personality. In short, a person not to be trifled with. According to 1860 federal records, before the Civil War T. W. Samuels owned five slaves: males, ages 38, 22 and 9; females, ages 19 ad 8.

Ironically, after the long years of the Deatsville distillery, a decision was made to personify a “gentler and kinder” T.W Samuels in company advertising. An artist’s image portrayed him as “the Ole” T. W., a goateed Southern gentleman with almost no resemblance to the original. This likeness was published in newspapers, featured on billboards, and added to the whiskey label, as shown on the image that opens this vignette. The distillery registered its first trademark in 1905, one that included the faux T. W. Samuels.

During more some four decades, W. I. Samuels worked at the distillery alongside his often domineering father. Thoroughly schooled in the art and science of making good whiskey, the adult W. I. gained a local reputation as a successful cattle breeder and for his civic work in Nelson County, including founding a school. More genial than his father, he became friends with members of the Beam family and popular with other local distillers.

When T. W. Samuels died in January, 1898 at the age of 77, cause not described, he was buried in the New Salem Baptist Church Cemetery in Nelson County. His memorial monument is shown below. The inscription reads: “How desolate our home bereft of thee.”

After waiting years to succeed his father, W. I. Samuels immediately took over management of the Deatsville Distillery. For decades he had worked there alongside his often domineering father. W. I.’s health was faltering, however, and only five months after his father’s death, in July 1898 he succumbed at age 52. W. I. was buried in the Bardstown City Cemetery, elsewhere from his father’s grave.

Now the mantle of Samuels whiskey making fell on W. I.’s son, Leslie Samuels, a change that ushered in a whole new chapter in the family’s whiskey saga. That story is the subject of my next post.

Note: A great deal of information about the generations of the Samuels distilling family can found on the Internet. This post is drawn from myriad sources. It is a matter of sorting out the details and trying to create a coherent narrative.

Labels: The Samuels family distilling, Robert Samuels jr., John Samuels, T. W. Samuels. W. I. Samuels, T.W. Samuels Kentucky Bourbon, Jesse James, Frank James

.

Samuels Family Distilling — Origins to Today, Part 1

Foreword: The story of the Samuels distilling family stretches from before the American Revolution until the present day, representing eight generations. Given the length and importance of the Samuels’ story, it is related here in two installments. The first part, below, traces Samuels distilling from its beginnings, to the Revolutionary War, through the Civil War and ends just before the turn of the 20th Century. The second part follows in four days.

The story of the Samuels family begins with John Samuels Senior, a clergyman for the Church of Scotland, living in the village of Samuelston outside of Edinburgh. After moving to Northern Ireland to preach, a decade later John Senior sailed on an early shipload of Scotch-Irish settlers coming to the American colonies. He settled in Pennsylvania. Little is known of his son, John Samuels Junior but almost certainly he was a farmer/distiller. In his will that Samuels left

a still to his son Robert Samuels. Again, little is known of Robert. He is recorded as a farmer/distiller, making rye whiskey in East Pennsboro Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. When he died, his 30 gallon still was passed on to his son, Robert Samuels Junior.

Born in 1755, Robert Junior was a Pennsylvania volunteer in the Revolutionary War, cited as having supplied whiskey for the troops. That he was distilling spirits seems indisputable, but there are at least two accounts of the war story. One version has Robert making whiskey for himself and sharing it with his fellow soldiers. A second version brings George Washington into the narrative.

Washington, as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, famously is quoted in his daily orders of August 7, 1776, decreeing that every soldier should have a daily ration of liquor “as an encouragement to them to behave well and to attend diligently to their duty.” Although the ration amounted to only four ounces of spirits a day, the order was highly popular with the troops. As the story goes, Washington commissioned Robert Junior to leave off other duties and concentrate full time making whiskey. He complied.

Successful at providing the much-desired spirits, Robert was honorably discharged from the Army following the end of the Revolutionary War. Returning to his home in Pennsylvania, he found that two brothers had claimed 60 acres of land for him near Bardstown in the then Kentucky region of Virginia under the Virginia’s Corn and Cabbage Patch Act of 1775. Robert soon moved his family to his new homestead. With him went a 60 gallon still. A member of a local militia, he served several seasons as an officer when not engaged on his farm growing corn and making whiskey. Thus began the Kentucky heritage of the Samuels family.

Robert’s son, John Samuels carried on the family tradition of distilling. As his father had discovered, although Kentucky had rich soil for growing grain, rye was not an entirely successful crop and corn was. John understood that his mash of corn worked equally well and that turning it into whiskey was an efficient way to transport the grain harvest and at the same time add value. About 1820, John built his family the stately looking Georgian home below. It became a gathering place for subsequent generations of the Samuels distilling clan. As seen right, today the house is a boutique hotel redolent with whiskey history.

In the early days of the Samuels distilling dynasty, the most prominent member of the family was John’s nephew, Taylor Williams Samuels, known as “T. W.” His claim to fame, however, went beyond distilling to becoming the lawman credited with the surrender of the Jesse and Frank James, cited by some as a final act of the American Civil War.

The story goes this way: As the Civil War was drawing to a close, a number of Confederate raiders, freed from the restriction of military control, roamed the Upper Midwest, pillaging and murdering the local populations. Among them were

future outlaws Jesse and Frank James. With their compatriots surrendering all around them, the James boys decided their best, perhaps only, option was to surrender and headed to Nelson County, Kentucky, and Bardstown, a city they knew well.

They were the sons of a Bardstown woman, known as the Widow Zerelda Sims, who earlier had been married to Robert James and the mother of his children. At the time the James boys arrived in town T. W. Samuels was High Sheriff of Nelson County and well known to them both. Mother Zerelda now was remarried to the sheriff’s brother, Ruben Samuels. Related by marriage, Sheriff Samuels wanted nothing to do with the brothers and urged Ruben to get them to leave.

Instead, their surrender was arranged. Jesse and Frank on July 4, 1865, met with Sheriff Samuels on the front porch of his general store and gave him their guns. Shown here, Frank’s weapon, a 1851 Colt revolver, can be viewed in a Bardstown museum. In retrospect, since this event came months after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, some consider this act as officially ending the Civil War. The James brothers rode out of Kentucky free men to begin their lives as outlaws and enter the annals of Western history.

Meanwhile T. W. was establishing himself as the first in the line of Samuels distillers to own and manage a true commercial operation. Beginning In 1844, and later working with his son, William Isaac Samuels, know as “W.I.”, T. W. Samuels undertook to move beyond his ancestors and build a large scale distillery. The site was a land grant estimated at 4,000 acres, nine and one half miles northwest of Bardstown. Near the village of Deatsville, the plant was constructed near a small station on the Bardstown and Springfield Branch of the L&N Railroad. Shown below, by 1886 the Samuels distillery was mashing an estimated 100 bushels a day, yielding 14 barrels of whiskey. It had two bonded warehouses with a storage capacity for 9,500 barrels.

The Samuels, operating as T. W. Samuels & Son Company, over a period of almost a half century continuously ramped up production. By 1890, they were mashing grain for 110 barrels daily. Insurance underwriter records noted that the distillery was of frame construction with a metal or slate roof. The property included two bonded warehouses, both iron-clad with metal or slate roofs. One warehouse was located 220 feet north of the still. A second one was nearby. The property also contained a “free” warehouse, not subject to federal supervision, in an old frame building. The Samuels also maintained a small loading and unloading depot on the rail line.

With corn for mashing readily available, good transportation for getting their whiskey to markets throughout the Ohio Valley and beyond, and a reputation for making good whiskey, business boomed. The father and son sold their whiskey under the brand name “T.W. Samuels Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey.” Over the decades, as shown here, the labels were varied from time to time. The

Throughout his life, T. W. was considered by his fellow Kentucky distillers as a strong-willed, sometimes contentious, personality. In short, a person not to be trifled with. According to 1860 federal records, before the Civil War T. W. Samuels owned five slaves: males, ages 38, 22 and 9; females, ages 19 ad 8.

Ironically, after the long years of the Deatsville distillery, a decision was made to personify a “gentler and kinder” T.W Samuels in company advertising. An artist’s image portrayed him as “the Ole” T. W., a goateed Southern gentleman with almost no resemblance to the original. This likeness was published in newspapers, featured on billboards, and added to the whiskey label, as shown on the image that opens this vignette. The distillery registered its first trademark in 1905, one that included the faux T. W. Samuels.

During more some four decades, W. I. Samuels worked at the distillery alongside his often domineering father. Thoroughly schooled in the art and science of making good whiskey, the adult W. I. gained a local reputation as a successful cattle breeder and for his civic work in Nelson County, including founding a school. More genial than his father, he became friends with members of the Beam family and popular with other local distillers.

When T. W. Samuels died in January, 1898 at the age of 77, cause not described, he was buried in the New Salem Baptist Church Cemetery in Nelson County. His memorial monument is shown below. The inscription reads: “How desolate our home bereft of thee.”

After waiting years to succeed his father, W. I. Samuels immediately took over management of the Deatsville Distillery. For decades he had worked there alongside his often domineering father. W. I.’s health was faltering, however, and only five months after his father’s death, in July 1898 he succumbed at age 52. W. I. was buried in the Bardstown City Cemetery, elsewhere from his father’s grave.

Now the mantle of Samuels whiskey making fell on W. I.’s son, Leslie Samuels, a change that ushered in a whole new chapter in the family’s whiskey saga. That story is the subject of my next post.

Note: A great deal of information about the generations of the Samuels distilling family can found on the Internet. This post is drawn from myriad sources. It is a matter of sorting out the details and trying to create a coherent narrative.

Labels: The Samuels family distilling, Robert Samuels jr., John Samuels, T. W. Samuels. W. I. Samuels, T.W. Samuels Kentucky Bourbon, Jesse James, Frank James

.

.

A German immigrant who ultimately settled in Salida, Colorado, John B. Demphy was a man of multiple talents, as cabinetmaker, bartender, saloonkeeper, whiskey blender, policeman, poultry farmer, truck driver, and justice of the peace. None of Demphy’s skills, however, could save the life of his highly promising only son.

A German immigrant who ultimately settled in Salida, Colorado, John B. Demphy was a man of multiple talents, as cabinetmaker, bartender, saloonkeeper, whiskey blender, policeman, poultry farmer, truck driver, and justice of the peace. None of Demphy’s skills, however, could save the life of his highly promising only son. After achieving adulthood, he anglicized his name to John Demphy and changed his occupation to tending bar. In that role the young immigrant caught the notice of a Buffalo newspaper in 1896 as the chief bartender at Buffalo’s Genesee Hotel, shown here. Demphy, 28, was in charge of a squad of barkeeps hired on to serve a New York convention of Tammany Hall politicians “and keep their thirst slaked…Johnnie worked so hard that he said last night he was sure the thousand or more Tammany men came up ‘Just to let the Irish see…Dutchmen work themselves to death.”

After achieving adulthood, he anglicized his name to John Demphy and changed his occupation to tending bar. In that role the young immigrant caught the notice of a Buffalo newspaper in 1896 as the chief bartender at Buffalo’s Genesee Hotel, shown here. Demphy, 28, was in charge of a squad of barkeeps hired on to serve a New York convention of Tammany Hall politicians “and keep their thirst slaked…Johnnie worked so hard that he said last night he was sure the thousand or more Tammany men came up ‘Just to let the Irish see…Dutchmen work themselves to death.” Despite the solid look of Salida, it was not a “get rich quick” opportunity for the newly arrived Demphy. It was not a Western boom town because of gold, oil or other underground wealth. But neither was Salida overflowing with saloons serving thirsty miners. Instead Demphey found regular employment working for James Collins at his popular downtown saloon at 104 F Street. The Irish owner and German barkeep apparently proved highly compatible. About 1910 Collins decided to retire and leave town. He sold the F Street saloon and his residence to Demphy. Shown below, the house, built about 1888, still stands, known as the Collins/Demphy House and on the Salida roster of historic buildings.

Despite the solid look of Salida, it was not a “get rich quick” opportunity for the newly arrived Demphy. It was not a Western boom town because of gold, oil or other underground wealth. But neither was Salida overflowing with saloons serving thirsty miners. Instead Demphey found regular employment working for James Collins at his popular downtown saloon at 104 F Street. The Irish owner and German barkeep apparently proved highly compatible. About 1910 Collins decided to retire and leave town. He sold the F Street saloon and his residence to Demphy. Shown below, the house, built about 1888, still stands, known as the Collins/Demphy House and on the Salida roster of historic buildings. Now Demphy had a saloon in his sole possession to manage and a large comfortable home in which to house Ruth and their two children. Seemingly having found the future he had been looking for, the saloonkeeper expanded his efforts. As shown below, he became the regional agent of Anheuser-Busch Company, a brewery then making a concerted marketing effort in the West. He also was offering customers at the bar drink tokens, a common tradition in Western saloons.

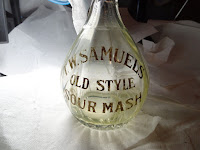

Now Demphy had a saloon in his sole possession to manage and a large comfortable home in which to house Ruth and their two children. Seemingly having found the future he had been looking for, the saloonkeeper expanded his efforts. As shown below, he became the regional agent of Anheuser-Busch Company, a brewery then making a concerted marketing effort in the West. He also was offering customers at the bar drink tokens, a common tradition in Western saloons. The transplanted New Yorker also expanded his efforts beyond simply dispensing booze over the bar into becoming a liquor wholesaler, supplying whiskey to the other saloons in Salida and vicinity. He was bringing supplies into town from distillers all over the region via the railroad —the station shown here, Demphy was “rectifying” (blending) whiskeys to achieve desired smoothness, color and taste, and selling them at wholesale in ceramic jugs, shown below and the image that opens this post.

The transplanted New Yorker also expanded his efforts beyond simply dispensing booze over the bar into becoming a liquor wholesaler, supplying whiskey to the other saloons in Salida and vicinity. He was bringing supplies into town from distillers all over the region via the railroad —the station shown here, Demphy was “rectifying” (blending) whiskeys to achieve desired smoothness, color and taste, and selling them at wholesale in ceramic jugs, shown below and the image that opens this post. Demphy’s biggest blow, however, was to come three years later. His son Marshall, shown here, had gained considerable attention in Salida as an outstanding youth. The Daily Mail wrote: “Marshall was gifted with a wonderful intellect and a special talent for drawing…attested by the many pen sketches which adorn his home and the Salida high school. In mechanical drawing he had achieved a degree of perfection rarely attained by anyone….Throughout his school life [he] secured numerous trophies at various track meets and athletic events.”

Demphy’s biggest blow, however, was to come three years later. His son Marshall, shown here, had gained considerable attention in Salida as an outstanding youth. The Daily Mail wrote: “Marshall was gifted with a wonderful intellect and a special talent for drawing…attested by the many pen sketches which adorn his home and the Salida high school. In mechanical drawing he had achieved a degree of perfection rarely attained by anyone….Throughout his school life [he] secured numerous trophies at various track meets and athletic events.” At the age of 18 Marshall was struck by spiral meningitis, treatable by antibiotics today but not available in that era. The malady was known to strike young people and often be fatal. The boy lingered for ten days in the grip of the disease while his anxious parents looked on at his bedside, and died on October 23, 1916. After a Catholic funeral service in the Demphy home, he was buried in Salidia’s Fairview Cemetery, Sec. G, Blk 23, Lot 12. His gravestone is shown here.

At the age of 18 Marshall was struck by spiral meningitis, treatable by antibiotics today but not available in that era. The malady was known to strike young people and often be fatal. The boy lingered for ten days in the grip of the disease while his anxious parents looked on at his bedside, and died on October 23, 1916. After a Catholic funeral service in the Demphy home, he was buried in Salidia’s Fairview Cemetery, Sec. G, Blk 23, Lot 12. His gravestone is shown here.