It was not uncommon for the proprietors of successful liquor houses to accumulate considerable wealth that they eventually invested in real estate development, banking institutions or new technologies like the automobile. A handful, however, made a reputation for having lavished their excess cash on fine art. Among them was Franklin O. Day, shown right, whose collection was accounted among the most notable of St. Louis, Missouri.

It was not uncommon for the proprietors of successful liquor houses to accumulate considerable wealth that they eventually invested in real estate development, banking institutions or new technologies like the automobile. A handful, however, made a reputation for having lavished their excess cash on fine art. Among them was Franklin O. Day, shown right, whose collection was accounted among the most notable of St. Louis, Missouri.

How Day became a connoisseur of fine art is not entirely clear. He was born in Burlington, Vermont, in October 1816 of native Vermonters Polly Mary and Alfred Day, a merchant whose ancestors came to America in 1634. The Days believed their family originated in Wales, not Ireland where the name is common, it originally having been written “Dee” but pronounced “Day.”

Day received a public school education but left off formal learning in mid-teens to work in his father’s dry good store. Apparently looking for larger opportunities at the age of 17 he went off to New York City where he found similar employment. The sudden death of his father in 1835 when Franklin was 19 called him back home to settle his father’s estate and run the business. When an business venture in a nearby town failed, Day reputedly with only $200 in his pocket headed West, settling in St. Louis.

Arriving in the Missouri town about 1842 or 1843, he soon found employment with T. S. Rutherford, a wholesale dry goods merchant. Within several years Day had so impressed his employer that he made him a junior partner. Within four years, Day had “so distinguished himself for efficiency” that he was made a full partner and the company name changed to Rutherford & Day.

Now an established St. Louis businessman, in 1849 Day found time to wed. His bride was Lavinia M. Aull, who had been born in Lexington, Missouri. In quick succession they had two sons, Frank P. and Harry. In succeeding years they would have two more children, Annie and Laurence.

Still restless at 38 years old, the excitement of the California Gold Rush (1848-1855) captured family man Day’s imagination. St. Louis was the starting point of many of the expeditions west and fortunes were being made herding livestock west across the plains to mining sites and boomtowns. Dissolving his partnership with Rutherford and kissing his family goodbye, in 1853 Day left on a cattle drive to California, a wearisome journey of almost six months, only to arrive “too late to reap the expected profit,” according to a biographer.

The profits were sufficient, however, for him to return with some money to St. Louis. There in 1855 he joined in a wholesale liquor business with Charles Derby, who earlier had established the enterprise at an address on the North Levee along the Mississippi, the area shown above as it looked at the time.

The profits were sufficient, however, for him to return with some money to St. Louis. There in 1855 he joined in a wholesale liquor business with Charles Derby, who earlier had established the enterprise at an address on the North Levee along the Mississippi, the area shown above as it looked at the time.  The company was called Derby & Day and featured several proprietary brands, including “Derby and Day Whiskey, “Superior Rectified,” and “Sunny South.” The latter was the firm’s flagship brand, sold in ceramic jugs and clear glass bottles. The company in 1873 trademarked both Sunny South and Derby and Day.

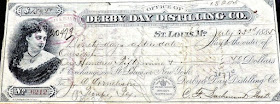

The company was called Derby & Day and featured several proprietary brands, including “Derby and Day Whiskey, “Superior Rectified,” and “Sunny South.” The latter was the firm’s flagship brand, sold in ceramic jugs and clear glass bottles. The company in 1873 trademarked both Sunny South and Derby and Day. Epitomized by the elaborate bank check shown below, the Derby & Day firm was highly lucrative. Said a biographer: “This enterprise…prospered, and from quite a moderate beginning grew to be one of the largest interests in the city, its name being a synonym for careful, judicious management and honorable dealing.” It also was making Day rich. The 1870 census found the Day family at home, the four children apparently in school, and five servants in the house. They included a seamstress, a cook, two house maids, and a carriage driver.

Epitomized by the elaborate bank check shown below, the Derby & Day firm was highly lucrative. Said a biographer: “This enterprise…prospered, and from quite a moderate beginning grew to be one of the largest interests in the city, its name being a synonym for careful, judicious management and honorable dealing.” It also was making Day rich. The 1870 census found the Day family at home, the four children apparently in school, and five servants in the house. They included a seamstress, a cook, two house maids, and a carriage driver. Increasingly Day was associating himself with St. Louis business leaders in such projects as the St. Louis bridge, shown right, and investing in the Merchants’ National Bank, Franklin Savings Bank, and Boatmen’s Insurance Company. At the same time he also was alert to a trend among leading wealthy St. Louisans to spend their excess riches by investing in works of art.

Increasingly Day was associating himself with St. Louis business leaders in such projects as the St. Louis bridge, shown right, and investing in the Merchants’ National Bank, Franklin Savings Bank, and Boatmen’s Insurance Company. At the same time he also was alert to a trend among leading wealthy St. Louisans to spend their excess riches by investing in works of art.

A 1911 History of St. Louis, described this phenomenon: “…The collection that came to be formed, as a result of the newly-awakened interest, gave by reflex influence a strong stimulus to that interest. The earliest of these collection worthy of mention began to be formed in the years immediately succeeding the close of the [Civil] war. A number of these have come to include not merely an extended array of pictures for which large sums of money have been paid, but pictures which, with very few exceptions, are genuine works of art of a high order of merit.”

That depends. Although the Impressionist movement was in its initial stages, few if any St. Louis collectors were interested in anything earlier than the 1930-1870 French Barbizon School. As for Franklin Day, his taste was clearly toward the traditionalist French and English salon and genre paintings. His reputation as a collector rested primarily on his purchase of a single painting for $10,000 — roughly equivalent today to $250,000. Painted by a Scottish artist, Erskine Nicol (1825-1905), shown here, the work was called “Paying the Rent,” one of the artist’s depictions of Scotch and Irish peasant life.

That depends. Although the Impressionist movement was in its initial stages, few if any St. Louis collectors were interested in anything earlier than the 1930-1870 French Barbizon School. As for Franklin Day, his taste was clearly toward the traditionalist French and English salon and genre paintings. His reputation as a collector rested primarily on his purchase of a single painting for $10,000 — roughly equivalent today to $250,000. Painted by a Scottish artist, Erskine Nicol (1825-1905), shown here, the work was called “Paying the Rent,” one of the artist’s depictions of Scotch and Irish peasant life.

Called “clever” by critics, the painting has been described as being…”Laid in the library of the agent of a estate, the tenant farmers are settling their rent with faces in which dissatisfaction is the chief expression.” The oil was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1866 and again at the Paris Exposition in 1867. Despite its reputation as one of Nicol’s most famous works, I have been unable to find an image of the painting and have here added a similar Nicol genre piece to illustrate Day’s taste in art.

Likely because of the price paid, Day’s purchase made headlines in St. Louis newspapers and led to his collection being identified among those which… “contain good and important examples of the work of nearly two hundred of the most celebrated of modern painters.” The whiskey man eventually seems to have tired of Nicol’s work and later sold it to Cornelius Vanderbilt, the railroad and shipping baron, who displayed it prominently in his New York City museum. I can find no mention of the sale price.

Day was at the helm of the St. Louis liquor house for 29 years. As his sons Frank P. and Laurence matured, he brought them into the employ of Derby & Day, respectively as bookkeeper and clerk. With advancing age, his health declined but he continue to take an active role in running the firm and said to have come to the office a week before his death in February, 1884. He was 66 years old. Day was buried Bellefontaine Cemetery of St. Louis, Block 55, Lot 1414. Shown here, a large marble monument crowned by three statues of toga-covered figures marks his grave, an arresting work of art on its own. Franklin would be joined there two years later by his widow, Lavinia.

Day was at the helm of the St. Louis liquor house for 29 years. As his sons Frank P. and Laurence matured, he brought them into the employ of Derby & Day, respectively as bookkeeper and clerk. With advancing age, his health declined but he continue to take an active role in running the firm and said to have come to the office a week before his death in February, 1884. He was 66 years old. Day was buried Bellefontaine Cemetery of St. Louis, Block 55, Lot 1414. Shown here, a large marble monument crowned by three statues of toga-covered figures marks his grave, an arresting work of art on its own. Franklin would be joined there two years later by his widow, Lavinia.

The last entry for Derby & Day Co. in local directories appears to be 1890, two years after Franklin’s death. Later directories show Frank P. and Laurence working at other occupations. The fate of Day’s art collection so far has escaped my research. I find no indication of a museum collection. Most likely it was sold at auction by his heirs and the individual works scattered widely.

Note: The details of Franklin Day’s life were contained in the History of Saint Louis City and County: From the Earliest Periods, Volume 2, by John Thomas Scharf published in 1883. A lengthy article in that book made special mention of the whiskey man’s interest in fine art.

No comments:

Post a Comment