At the age of 41, Charles H. Godwin in 1914 took a sharp turn in life. Even assuming a new name, he threw himself into creating a mail order liquor house in Monroe, Louisiana. In an extraordinary merchandising flyer, Godwin, shown right, addressed himself to the public as someone “…Who has grown up with this country, who is ambitious to know every man up and down the road, and who backs with every resource at his command the truths of our motto ‘HAL-WIN LIQUORS ALWAYS SATISFY.’”

At the age of 41, Charles H. Godwin in 1914 took a sharp turn in life. Even assuming a new name, he threw himself into creating a mail order liquor house in Monroe, Louisiana. In an extraordinary merchandising flyer, Godwin, shown right, addressed himself to the public as someone “…Who has grown up with this country, who is ambitious to know every man up and down the road, and who backs with every resource at his command the truths of our motto ‘HAL-WIN LIQUORS ALWAYS SATISFY.’”

He was born Charles Henry Godwin on October 16, 1873, in Opelousas, Louisiana, the third child of John W. Godwin, a native of Alabama, and Lucy L. Mathews, born in Mississippi. His family called him “Hal.” The family moved frequently during Godwin’s early years, by 1880 settling in Rayville, Louisiana, a small town some 22 miles directly west of Monroe. There Godwin would grow up, be educated, and find early employment in local businesses, likely ones that sold liquor.

In 1899 at the age of 25, Charles married Leila McCreight, 18 and a native of Louisiana. They would raise a family of five children, two daughters and three sons. With the financial needs of his growing family a likely factor, early in the 1900s he struck out on his own, under the name “C. H. Godwin.” In 1905 he was recorded operating a grocery and saloon in Mer Rouge, a hamlet 30 miles north and a bit east of Monroe.

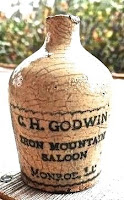

This may have been a relatively short-lived enterprise since in 1907 he was engaged in Monroe, running the Iron Mountain Saloon, located at 519 Ouachita Avenue and later at 315 South Second Street. According to one source, “Iron Mountain” did not refer to a geographical site but to the name of an railroad. As shown here in a 1913 Monroe business directory, Godwin described himself as a “wholesale and retail dealer in wines, liquors and cigars.” At some point he issued a mini-jug of whiskey to favored customers.

This may have been a relatively short-lived enterprise since in 1907 he was engaged in Monroe, running the Iron Mountain Saloon, located at 519 Ouachita Avenue and later at 315 South Second Street. According to one source, “Iron Mountain” did not refer to a geographical site but to the name of an railroad. As shown here in a 1913 Monroe business directory, Godwin described himself as a “wholesale and retail dealer in wines, liquors and cigars.” At some point he issued a mini-jug of whiskey to favored customers.

While operating this enterprise, however, Godwin saw another opportunity. All around him Monroe liquor dealers were cashing in on the effects of the prohibition movement. States in the South and West one by one had gone “dry.” Under local option laws individual towns and counties even in “wet” states were banning alcohol sales. It remained legal, however, to ship liquor interstate into those areas. Moreover, the few Louisiana jurisdictions to vote themselves “dry” still could be reached with impunity. Monroe, with good rail access to points around the compass, became a center of mail order liquor sales. Complained an official of “dry” Shreveport: “Such a farce is the law in this State that Monroe, La., alone, shipped 3,000,000 drinks into Shreveport last Christmas.”

Now calling himself C. Hal Godwin, the saloonkeeper made a pivot from selling drinks over the bar to seeking mail order sales through a company he called “Hal-Win Distilling Co..The Systematic Shipping House.” It was a costly move. He bought in an experienced supervisor named Bernard Seligman to run his office and shipping room. Seligman, Godwin claimed, “gave up a position as the head of the largest Mail Order house in Virginia to associate himself with the house with the big future — HAL WIN DIST. CO.”

Godwin also had made a deal with the Bernheim Bros. Distillery in Louisville for whiskey, noting “…It has cost us tremendous money to make this new connection.” The link with the noted Kentucky whiskey maker likely was something of a coup, giving C. Hal some advantage over his Monroe competition. Shown throughout this post are examples of his ads pushing Bernheim’s brands, such as Old Continental Whiskey and the flagship I. W. Harper Rye.

Godwin also had made a deal with the Bernheim Bros. Distillery in Louisville for whiskey, noting “…It has cost us tremendous money to make this new connection.” The link with the noted Kentucky whiskey maker likely was something of a coup, giving C. Hal some advantage over his Monroe competition. Shown throughout this post are examples of his ads pushing Bernheim’s brands, such as Old Continental Whiskey and the flagship I. W. Harper Rye.

Shaw’s Malt Whiskey was another Bernheim product, sold as for its medicinal value and advertised as “What the Doctor Ordered! A Mild Stimulant & Tonic to Build up & Strengthen — to Enrich the Blood & Steady the Nerves.” A Godwin illustration shows a physician ministering this “tonic and beverage,” one that “tastes like nectar,” to an elderly man and woman.

Godwin also featured his own proprietary house brands, including “Hal-Win Green Label” and “Hal-Win Cream of Monroe.” It is unclear whether he was receiving the whiskey for these blends directly from Bernheim Bros. or mixing them up in his own facility. While Old Continental from the Louisville distillery cost $1.25 a quart, Green Label was $1.00 and Creme of Monroe 80 cents for the same quantity. Godwin never bothered to trademark either label but did issue advertising shot glasses for his brands.

Godwin also featured his own proprietary house brands, including “Hal-Win Green Label” and “Hal-Win Cream of Monroe.” It is unclear whether he was receiving the whiskey for these blends directly from Bernheim Bros. or mixing them up in his own facility. While Old Continental from the Louisville distillery cost $1.25 a quart, Green Label was $1.00 and Creme of Monroe 80 cents for the same quantity. Godwin never bothered to trademark either label but did issue advertising shot glasses for his brands. In a long introductory flyer introducing his new company, Godwin summed up by noting that in addition to getting Bernheim’s whiskey and Seligman’s experience, a customer could count on “the constant personal interest and watchfulness of your old friend C. Hal Godwin….” He concluded with the statement that opened this post, his ambition to meet every man “up and down the road.”

In a long introductory flyer introducing his new company, Godwin summed up by noting that in addition to getting Bernheim’s whiskey and Seligman’s experience, a customer could count on “the constant personal interest and watchfulness of your old friend C. Hal Godwin….” He concluded with the statement that opened this post, his ambition to meet every man “up and down the road.” Although the quality of Godwin’s marketing materials clearly was superior to most of his day, a question remains of their results. Although none of his materials are dated, he appears to have initiated his efforts about 1912, late in the game for selling whiskey by mail. Congress shortly would make it illegal to sell liquor across state lines into “dry” states and localities. Although most of Louisiana was predictably “wet,” even there as a result of local option more and more localities had banned alcohol. Godwin also faced considerable established competition, including from other Monroe liquor dealers. [See my post on Rufus Webb, March 2014.] Finally in 1913 he suffered a warehouse fire in which whiskey stocks worth the equivalent today of $250,000 were destroyed.

Although the quality of Godwin’s marketing materials clearly was superior to most of his day, a question remains of their results. Although none of his materials are dated, he appears to have initiated his efforts about 1912, late in the game for selling whiskey by mail. Congress shortly would make it illegal to sell liquor across state lines into “dry” states and localities. Although most of Louisiana was predictably “wet,” even there as a result of local option more and more localities had banned alcohol. Godwin also faced considerable established competition, including from other Monroe liquor dealers. [See my post on Rufus Webb, March 2014.] Finally in 1913 he suffered a warehouse fire in which whiskey stocks worth the equivalent today of $250,000 were destroyed. Whatever the immediate outcome, the Hal-Win Distilling Company was doomed to be short-lived as National Prohibition was approved in 1919 and the alcohol ban became the law all across the country. Godwin was forced to shut down his mail order liquor house and his Iron Mountain Saloon. Sometimes listed as Charles H. and sometimes as C. Hal, Godwin’s occupation subsequently was recorded as insurance salesman (1929) and as a director of an oil and gas company (1933). His home was at 501 Pine Street, shown here.

Whatever the immediate outcome, the Hal-Win Distilling Company was doomed to be short-lived as National Prohibition was approved in 1919 and the alcohol ban became the law all across the country. Godwin was forced to shut down his mail order liquor house and his Iron Mountain Saloon. Sometimes listed as Charles H. and sometimes as C. Hal, Godwin’s occupation subsequently was recorded as insurance salesman (1929) and as a director of an oil and gas company (1933). His home was at 501 Pine Street, shown here. Godwin died in Monroe in 1954 at the age of 80 and was buried there in Riverview Cemetery. His gravestone is shown here. His wife, Leila, had preceded him there, dying in 1946. Also interred near the couple was their son, Charles Hal Goodwin. Enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1922, Charles Hal, 18, died in basic training during an influenza epidemic.

Godwin died in Monroe in 1954 at the age of 80 and was buried there in Riverview Cemetery. His gravestone is shown here. His wife, Leila, had preceded him there, dying in 1946. Also interred near the couple was their son, Charles Hal Goodwin. Enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1922, Charles Hal, 18, died in basic training during an influenza epidemic.

No comments:

Post a Comment