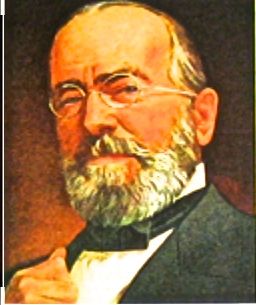

Murphy’s march to economic prominence began modestly when he was born in 1842 on a farm in Platte County, Missouri, the son of William S. and Amelia Tyler Murphy, both originally from Pennsylvania. His family was able to send him to a private school until he was 17. Then drawn by the news of gold strikes Murphy headed West, settling initially in Denver where he clerked in a store.

That was the last time Murphy ever worked for someone else. As one biographerput it: “It seems John Murphy was one of those rare individuals who could touch anything and turn it to gold.” By 1863 he had moved to Nevada City. Colorado, where he opened his own store, one selling liquor among other supplies. Sensing the end of the gold mining boom there, Murphy loaded a wagon with merchandise, including whiskey, and headed 800 miles northwest to Virginia City, Montana, Gold had been discovered there in May 1863. Within weeks Virginia City had become a boomtown of thousands of prospectors and fortune seekers in the midst of a gold rush.

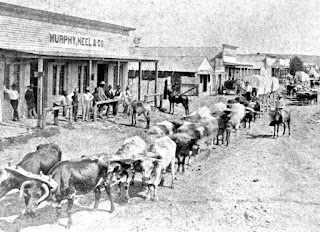

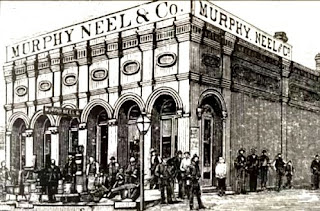

With local partner Sam Neel, Murphy opened a general store in Helena. A photo of the establishment indicates it was a “false front” structure on the main street where the owners could watch the ox-drawn Conestoga wagons rattle through town. To fetch supplies Murphy floated down the Missouri River on a flatboat to Nebraska City, Nebraska, a commercial center for goods brought by steamboat via the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. There he ordered merchandise to be transported overland to Helena the following spring. Continuing downriver to St. Louis, he ordered more goods to be shipped by steamboat to Fort Benton, a port on the Upper Missouri River, then to be carried overland 130 miles to Helena.

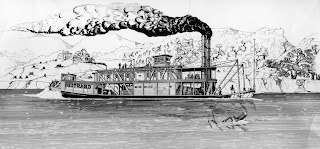

|

| The Bertrand |

Stowed aboard the ill-fated Bertrand, Murphy’s supplies ended at the bottom of the Missouri River. In 1968, more than 100 years later, private salvagers discovered the wreck in an area of the river managed by the U.S. Department of the Interior. Since the boat was found on government property the recovered artifacts were relinquished to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for permanent preservation. More than 10,000 cubic feet of cargo and over 500,000 artifacts were recovered from the hold during excavation and now are on display at the museum of the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge near Missouri Valley, Iowa.

Consignment records indicate that a considerable quantity of the whiskey and other liquor on board, including alcoholic bitters, were destined for Murphy & Neel in Helena. The whiskey bottles long since have had their labels washed away. They largely are un-embossed and identifying the brands is impossible. In contrast the bitters bottles have distinctive shapes and are embossed. Illustrated here, they held “Drake’s Plantation Bitters,” “Dr. J. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters,” “Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters,” and “J. H. Schroeder Stomach Bitters.” The first three brands through national advertising likely had a customer base even in far off Montana. The fourth bitters was less well known, the product of a Louisville wholesale liquor house.

During this period, Murphy was engaged in a courtship with Elizabeth Morton, the daughter of William and Adaliza Thornton of Clay County, Missouri. Although John was eleven years older than Elizabeth neither were young at the time of their marriage — the groom 57; the bride, 46. They married at her home and left for Montana the following spring. They would have four children. Of Elizabeth, a newspaper obituary said: “It is allotted to few to have more friends than Mrs. Murphy. Those who knew her best, loved her best. She was one of the most unselfish of women. Her life was one succession of good deeds.”

Now among Montana’s richest businessmen, Murphy expanded his activities into banking, helping to organize the Helena National Bank in 1891 and a year later creating the Montana Savings Bank. His mining interests included investments in the Poorman, Jay Gould, Rumley and Silver Bell mines. From his winter home in Fort Meyers he is reported to have invested in Florida citrus farming.

In his later years, through death Murphy lost some of those closest to him. In 1897 after a short illness that initially did not seem serious, his wife Elizabeth succumbed to a malady described in the press as “brain fever.” After a few months, Murphy married again. She was Clara Cobb, originally from Providence, Rhode island. Several years later a young son died, followed by his partner, Sam Neel, still only 34 years old. After what a biographer called “a long and exhausting career,” John T. Murphy himself died in May 1914 and was buried beside Elizabeth in Helena’s Forestvale Cemetery.

Over his lifetime, Murphy, the Western tycoon, had carved out an empire of productive enterprises that made him one of the richest men in the West. More than a century later the raising of the Bertrand confirmed the principal beginnings of his wealth — selling whiskey and other forms of alcohol.

Notes: This post was drawn from a variety of sources. Chief among them were “The Steamboat Bertrand and Missouri River Commerce” and “A Study of 19th Century Glass and Ceramic Containers,” both by Roland R. Switzer; “Progressive Men of Montana, Illustrated,” A. G. Bowen & Co., 1902; and George T. Armitage, “Prelude to the Last Roundup: the Dying Days of the Great 79,” Montana, Vol II, No. 4. Historical Society of Montana.