|

| Abe Reuf |

He was Abe Reuf, the political boss of San Francisco. Born Abraham Rueff from French-Jewish parents, he was a bright student and, when barely fourteen, began studying at the University of California, Berkeley, majoring in classical studies. While attending the university, Reuf developed an interest in fighting the rampant corruption that was endemic to local politics and helped form a “Municipal Reform League.” But a love for money and power later took him to the “dark side” of the spectrum. Electing his own man, “Handsome” Eugene Schmitz, a violinist and union chief, as mayor in 1901 Ruef was prepared to accrue as much graft as possible. He made the Hilberts a proposition that amid their financial woes the brothers accepted.

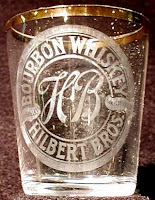

The brothers hired Reuf as their attorney at the then princely sum of $500 a month ($16,500 equivalent today). Subsequently Reuf’s name on their business card was larger than their own. They also made Mayor Schmitz a silent partner in their operation, paying him a commission of $50 ($1,600 equiv.) for every barrel of whiskey sold. In return the Mayor and his agents pushed the saloons of San Francisco to buy whiskey solely from the brothers through their newly named Hilbert Mercantile Company.

|

| Mayor Schmitz |

Both Colliers and McClure’s magazines, known as “muck-raking” (read “investigative”) journals published expose’ articles on the Ruef-Schmitz cabal. McClure’s explained the liquor scheme: After the Hilberts made contracts with Eastern distillers for cheap whiskey at 52-85 cents a gallon, the Mayor and his henchmen forced local saloonkeepers and brothel owners to pay $3.50 a gallon for the substandard booze to avoid trouble. A portion of the profit was kicked back by the brothers to city officials. The Hilberts did not always require cash for their whiskey but also took promissory notes for sales. They then sold the notes at discount through San Francisco banks.

Because of evident ties to City Hall the Hilberts’ liquor became widely known as “municipal whiskey.” Christopher and Fred may not have cared; the money rolled in. As McClure’s noted: “The saloonkeepers, of course, dared not refuse to take the Hilbert whiskey, because their licenses had to be renewed every three months and if they should insist on their right to buy where they chose, they might be forced out of business.”

That situation changed drastically on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, with the great San Francisco earthquake and devastating fire. Some believe the Hilbert Mercantile Company was among those businesses destroyed in the conflagration; others are not so sure. Mayor Schmitz tried to put the best face on the catastrophe by piloting a street car through the wreckage, a stunt that briefly made him popular. There was, however, no way of restoring the “municipal whiskey" scam. When the promissary notes came due, Hilbert Mercantile Company declared bankruptcy leaving holders “high and dry.”

Fred eventually came back to California but dropped out of sight. Before the earthquake and fire he had been recorded living in San Francisco with his wife Amelia and their two daughters. In the 1910 census the family was still there. Fred, however, was absent from the home. He resurfaced in Vallejo in 1915.

Meanwhile, Schmitz and Reuf were convicted of extortion and bribery in a San Francisco courtroom. Reuf was sent to San Quentin Prison. The office of mayor was declared vacant while Schmitz was sent to jail to await sentence. Shortly thereafter, he was given five years at San Quentin, the maximum sentence the law allowed. He immediately appealed; while awaiting the outcome, he was kept in a cell in the San Francisco County Jail. After having his sentence reversed by higher courts, Schmitz twice ran for office again and was soundly defeated both times.

After returning to the U.S. from the Philippines Christopher Hilbert relocated to New York City working as a commission merchant. That occupation allowed him to travel widely to Europe and Asia, often with his wife, Marie Robbins, and their two daughters. Christopher died at the age of 61 in February 1928 at a hotel in Capri, Italy. Cremated in Rome, his widow had his ashes buried in his natal Hamburg. Meanwhile Fred was employed in a variety of occupations that resulted in his family frequently moving around California. After his wife died, Fred eventually returned to living in San Francisco and died there in 1945, age 82. He was buried in Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma.

In contrast to Reuf and Schmitz, despite their active participation in one of San Francisco’s most blatant extortion schemes, inexplicably neither Hilbert brother was ever charged with a crime.

Note: An embossed bottle led me to the great amount of information available on the Internet about the Hilberts and their activities in a corruption-ridden San Francisco. A prime source was material at the “Virtual Museum” of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). The Colliers and McClure’s articles on the Reuf-Schmitz ring were key to understanding how the “municipal whiskey” extortion operated and the integral role played by the Hilbert brothers.

No comments:

Post a Comment