Philip Bissinger, a saloonkeeper in Reading, Pennsylvania, lived a tale of horror that closely resembled the plot of the Greek tragedy “Medea” by Euripides. In the play Medea is thrown over by her husband, Jason, for another woman. She then takes her revenge by killing their children. Jason is blamed by both the gods and men and dies ignominiously. Could Bissinger, shown here in later life, evade that fate?

Philip Bissinger, a saloonkeeper in Reading, Pennsylvania, lived a tale of horror that closely resembled the plot of the Greek tragedy “Medea” by Euripides. In the play Medea is thrown over by her husband, Jason, for another woman. She then takes her revenge by killing their children. Jason is blamed by both the gods and men and dies ignominiously. Could Bissinger, shown here in later life, evade that fate?

The real life tragedy unfolded on a sunny August day in 1875 when Bissinger’s wife, a pregnant Louisa, took their three children, Lillie (age 9), Mollie (age 6), and Philip (age 3) on a trolley to Reading’s Penn Street Bridge, crossed the span and walked them two miles down a canal towpath to the area of Gring’s Mill and Lock No. 49 East. Shown here in a newspaper sketch, Louisa was carrying a basket and told the children they were going to have a picnic.

The real life tragedy unfolded on a sunny August day in 1875 when Bissinger’s wife, a pregnant Louisa, took their three children, Lillie (age 9), Mollie (age 6), and Philip (age 3) on a trolley to Reading’s Penn Street Bridge, crossed the span and walked them two miles down a canal towpath to the area of Gring’s Mill and Lock No. 49 East. Shown here in a newspaper sketch, Louisa was carrying a basket and told the children they were going to have a picnic.

Once thy reached the spot, shown below, Louisa loaded the basket with rocks, some of which at her direction the children had picked up along the way. She then tied the basket to her waist, grabbed hold of the unsuspecting children, and plunged with them into the murky waters of the canal. Weighed down by the stones, the mother sank immediately. Although she lost her grip on the children,they could not swim and struggled to stay afloat. The only onlooker, a non-swimmer, ran for a boat but was too late. By the time he reached them Louisa and all three children had drowned, along with the unborn in her womb. Below are photos of the site of the drownings.

The press reported that Louisa’s commission of this final desperate act came about as the culmination of her husband’s longtime “undo respect” toward her and his open affair with another woman whom he eventually brought into their home. A newspaper story, datelined “Reading, Pa., August 21,” claimed that an argument had led to Bissinger ordering Louisa from their living quarters and told to take the two girls, but to leave their son. Louisa, not known previously to have emotional problems, seemingly had been “driven to the wall” and decided to kill herself as well as her offspring.

Inflamed by press accounts, the mood in Reading was ugly. An estimated 5,000 people showed up to view the four bodies at a wake in Bissinger’s saloon and to shout at the proprietor, shown left in an unflattering newspaper drawing. Calling Bissinger “a monster,” the crowd accused him of causing the deaths. He needed five police escorts to Reading’s Charles Evens Cemetery where the four were buried in a single grave. Mourners followed the hearses and continued their verbal assaults against Bissinger.

Inflamed by press accounts, the mood in Reading was ugly. An estimated 5,000 people showed up to view the four bodies at a wake in Bissinger’s saloon and to shout at the proprietor, shown left in an unflattering newspaper drawing. Calling Bissinger “a monster,” the crowd accused him of causing the deaths. He needed five police escorts to Reading’s Charles Evens Cemetery where the four were buried in a single grave. Mourners followed the hearses and continued their verbal assaults against Bissinger.

The crowd’s fury reached a crescendo during funeral services at the grave. Onlookers screamed, “Hang him!”. Two gunshots were said to have been aimed in Bissinger’s direction. Finally a mob estimated at more than 1,000 rushed toward him, apparently determined to “string him up.” Police intervened and got Bissinger into a carriage and escorted him out of the area.

The media and community continued to heap scorn on Bissinger until he felt obliged to respond. In a lengthy statement to the press, the saloonkeeper asserted: “I deny maltreatment, threatening her life, insulting her, offering her money to separate, improper intercourse with others, and I did not neglect to provide or care for my wife and children.” Earlier in his statement, however, Bissinger exposed his controlling personality: “Louisa and I had a difference in character and disposition, plus I asked her to have an inclination to let go of her individuality and natural spirit to ensure happiness. I requested she…mend her womanly failings, which caused us great problems…My unhappy wife failed to understand how to assimilate herself with my disposition….”

Livid at the response from Bissinger, her brother, Fred, responded in the press on behalf of her family. Among his allegations: “Captain Phillip Bissinger married Louisa then distanced her from her family. My family was never allowed to see Louisa or her children. Louisa was a tortured and weak woman who was quite literally tortured to misery and death!….Captain Philip Bissinger and the strumpet he ran around with caused the ruin of Louisa’s family. She couldn’t let someone else raise her children….”

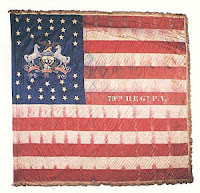

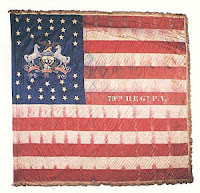

After these exchanges, Bissinger apparently never publicly addressed the events at Lock 49 East again but set about trying to restore his reputation in Reading as a respected citizen. Among the his assets was his service in the Civil War. Born in Germany and brought to America as a boy, he was schooled in Pennsylvania and in the Civil War joined the 79th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment, whose battle flag is shown here. Compiling a distinguished war record, Bissinger rose from the enlisted ranks to become the captain of the regiment’s Company F. He would be called “captain” for the rest of his life.

After these exchanges, Bissinger apparently never publicly addressed the events at Lock 49 East again but set about trying to restore his reputation in Reading as a respected citizen. Among the his assets was his service in the Civil War. Born in Germany and brought to America as a boy, he was schooled in Pennsylvania and in the Civil War joined the 79th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment, whose battle flag is shown here. Compiling a distinguished war record, Bissinger rose from the enlisted ranks to become the captain of the regiment’s Company F. He would be called “captain” for the rest of his life.

Bissinger also could point to his success as a Reading businessman. At his marriage to Louisa her family had gifted him with one of their businesses, a restaurant and saloon, that he renamed “Cafe Bissinger.” Located in a large building at 611 Penn Street it became one of Reading’s most prominent and prestigious eateries and meeting places. As indicated in an ad, Bissinger also was selling liquor, wine and beer both at wholesale and retail from the premises.

Bissinger also could point to his success as a Reading businessman. At his marriage to Louisa her family had gifted him with one of their businesses, a restaurant and saloon, that he renamed “Cafe Bissinger.” Located in a large building at 611 Penn Street it became one of Reading’s most prominent and prestigious eateries and meeting places. As indicated in an ad, Bissinger also was selling liquor, wine and beer both at wholesale and retail from the premises.

Later he would go on to co-found the Reading Brewing Company, a highly successful enterprise providing substantial employment for the city.

Moreover, for two decades (1864-1883) Bissinger was highly influential and successful in the cultural life of Reading. When two German singing societies merged there, he was chosen as the director. Bissinger went on to become musical director of the Germania Orchestra, one chosen to play at the U.S. Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia. Described as a “musician of ability,” in 1879 Bissinger organized the Philharmonic Society of Reading and directed its concerts for four years.

Moreover, for two decades (1864-1883) Bissinger was highly influential and successful in the cultural life of Reading. When two German singing societies merged there, he was chosen as the director. Bissinger went on to become musical director of the Germania Orchestra, one chosen to play at the U.S. Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia. Described as a “musician of ability,” in 1879 Bissinger organized the Philharmonic Society of Reading and directed its concerts for four years.

The saloonkeeper also was cautious about pursuing his affair with “the other woman” who reputedly had precipitated the tragic events of 1875. Described in one news story as a “femme fatale” from Philadelphia, Bissinger’s amorata was in fact a Reading native named Ida Sebald Rosenthal, the daughter of William Rosenthal a journalist and founder of the Reading Post. Ida, an accomplished musician, was eight years younger than Philip. While no doubt continuing their relationship Bissinger waited until 1880, five years after the drownings, to marry Ida, apparently expecting — correctly, it seems — that public anger would dissipate. Despite having housed Louisa and their children in quarters above Cafe Bissinger, for Ida the new bridegroom promptly built a spacious home, shown here, on Readings’ Mineral Spring Road. They would have no children.

The saloonkeeper also was cautious about pursuing his affair with “the other woman” who reputedly had precipitated the tragic events of 1875. Described in one news story as a “femme fatale” from Philadelphia, Bissinger’s amorata was in fact a Reading native named Ida Sebald Rosenthal, the daughter of William Rosenthal a journalist and founder of the Reading Post. Ida, an accomplished musician, was eight years younger than Philip. While no doubt continuing their relationship Bissinger waited until 1880, five years after the drownings, to marry Ida, apparently expecting — correctly, it seems — that public anger would dissipate. Despite having housed Louisa and their children in quarters above Cafe Bissinger, for Ida the new bridegroom promptly built a spacious home, shown here, on Readings’ Mineral Spring Road. They would have no children.

Bissinger’s strategy of staying the course of his career in Reading paid off. Public anger about his treatment of Louisa faded and soon people seemed to forget about his misdeeds. Eventually, without public outcry, Bissinger was able to be appointed by Reading’s City Council as park commissioner. He served from 1891 to 1897.

In 1910 after 30 years of marriage, Ida, who had been in ill-health for some time, died in the couple’s home of what her obituary called “complications.” Philip lived on another 16 years, but eventually sold his saloon and liquor business. Bissinger’s death certificate put the immediate cause as pneumonia brought on by heart disease. The couple lay buried in the same Reading cemetery that contains the joint graves of Louisa and the children.

Although events surrounding the Reading tragedy bear important resemblances to the Medea story, the impact on the husbands involved could not be different. Jason, the unfaithful spouse of Euripides' tragedy, having alienated the Greek chorus and more important, the gods, died lonely and unhappy. He was said to be sleeping on the stern of his rotting ship when it collapsed, killing him instantly. Bissinger, by contrast, earned a lengthy complimentary write-up in a 1909 volume of Berks County biographies. No mention is made of his first marriage or the drownings. The article concludes: “He possesses a genial and good natured disposition, is a pleasant conversationalist, and has scores of friends throughout this section.”

Although events surrounding the Reading tragedy bear important resemblances to the Medea story, the impact on the husbands involved could not be different. Jason, the unfaithful spouse of Euripides' tragedy, having alienated the Greek chorus and more important, the gods, died lonely and unhappy. He was said to be sleeping on the stern of his rotting ship when it collapsed, killing him instantly. Bissinger, by contrast, earned a lengthy complimentary write-up in a 1909 volume of Berks County biographies. No mention is made of his first marriage or the drownings. The article concludes: “He possesses a genial and good natured disposition, is a pleasant conversationalist, and has scores of friends throughout this section.”

The story does not end there. Since the 1875 tragic deaths of Louisa, Mollie, Lillie, Philip and an unborn child, Gring’s Mill’s Lock #49 regularly has been the site of ghostly sightings. For example, two nuns walking the canal towpath encountered two little girls in Amish-looking clothing who were soaking wet. After they passed the nuns turned to look again and the girls had vanished. Lillie and Mollie?

Note: Newspaper and other articles abound on the story told here. Two principal sources were “The Historical and Biographical Annals of Berks County Pennsylvania,” by Morton Montgomery, 1909, and “Reading’s Famous Ghost Family” by Printz, The Reading Eagle, October 18, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment