Abraham Bomberger, shown here, and his two sons were Pennsylvania distillers who were part of a long liquor-making tradition while at the same time recognized as pioneers in the American whiskey industry. They also could boast that they ran the longest continuously operating distillery in America.

Abraham Bomberger, shown here, and his two sons were Pennsylvania distillers who were part of a long liquor-making tradition while at the same time recognized as pioneers in the American whiskey industry. They also could boast that they ran the longest continuously operating distillery in America. The Bombergers were Mennonites, a Christian sect that, escaping sectarian prejudice in Europe, were some of the earliest settlers in Pennsylvania, a state known for its religious tolerance. Mennonites in Europe for years had been engaged in distilling, the liquor trade and barkeeping. In northeastern Germany the terms “Mennonite” and “tavern” became almost synonymous, according to historians. Adherents literally had been forced into the trade after being barred from most other occupations by vocational guild restrictions.

Thus was natural that when Mennonite John Shenk and his brother Michael settled on Snitzel Creek near present day Schaefferstown, Lebanon County, he built a distillery in 1753, more than two decades before the Revolutionary War. Handed down within the Shenk family for more than a century, it was sold to Abraham Bomberger in 1860, top right. He was a Shenk descendant through his mother, Elizabeth Shenk Bomberger.

Abraham also was a Mennonite, steeped in the tradition of that religious belief. Six years after after purchasing the distillery in 1866 he married Catherine Horst, shown above. She was the daughter of Samuel Horst and Catherine Schaeffer of Schaefferstown. Abe and Catherine would have two sons, Horst, born 1867, and Samuel, born 1879.

Thus was natural that when Mennonite John Shenk and his brother Michael settled on Snitzel Creek near present day Schaefferstown, Lebanon County, he built a distillery in 1753, more than two decades before the Revolutionary War. Handed down within the Shenk family for more than a century, it was sold to Abraham Bomberger in 1860, top right. He was a Shenk descendant through his mother, Elizabeth Shenk Bomberger.

Abraham also was a Mennonite, steeped in the tradition of that religious belief. Six years after after purchasing the distillery in 1866 he married Catherine Horst, shown above. She was the daughter of Samuel Horst and Catherine Schaeffer of Schaefferstown. Abe and Catherine would have two sons, Horst, born 1867, and Samuel, born 1879.  The Shenks had been farmer-distillers, turning home grown rye and corn into whiskey for local consumption. Abe Bomberger had bigger ideas. He rebuilt and expanded the still house, shown here, as well as the warehouse and the jug house. With these facilities he was able to increase production substantially. As a National Historical Landmark designation states: His complex “represents the transformation of whiskey distilling from an agricultural enterprise into a large scale industry.” An ad in an 1875 directory, shown here, emphasizes the primacy of distilling in Abraham’s endeavors.

Under his leadership Bomberger whiskey began to attract a wider region audience, requiring the hiring of non-family workers. Several are shown here, outside the distillery.

The Shenks had been farmer-distillers, turning home grown rye and corn into whiskey for local consumption. Abe Bomberger had bigger ideas. He rebuilt and expanded the still house, shown here, as well as the warehouse and the jug house. With these facilities he was able to increase production substantially. As a National Historical Landmark designation states: His complex “represents the transformation of whiskey distilling from an agricultural enterprise into a large scale industry.” An ad in an 1875 directory, shown here, emphasizes the primacy of distilling in Abraham’s endeavors.

Under his leadership Bomberger whiskey began to attract a wider region audience, requiring the hiring of non-family workers. Several are shown here, outside the distillery. As his sons reached maturity, he changed the name of his operation to Abraham Bomberger and Sons. With Abe’s death in 1904, Horst, in partnership with Samuel, took over the operation of the distillery and changed its name once again to “H.H. Bomberger,” as shown on a circa 1910 label.

Horst, shown here with his son Paul, appears to have been a demanding individual. About 1915, age 48, he suffered a stroke, was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease, and was confined to a wheelchair. His pressures on Paul apparently were so onerous that the young man ran way, changed his name to Frank Smith and joined a circus.

Horst, shown here with his son Paul, appears to have been a demanding individual. About 1915, age 48, he suffered a stroke, was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease, and was confined to a wheelchair. His pressures on Paul apparently were so onerous that the young man ran way, changed his name to Frank Smith and joined a circus.

Although infirm, Horst with Samuel kept the distillery going until the advent of Prohibition. What happened then was subsequently reported: “On the last day before the distillery closed down in 1919, customers came on that cold day to fill casks, bottles and tin cups and to drink their last rations of legal whiskey until Prohibition was repealed in 1933.” With the advent of Prohibition 167 years of Mennonite distilling tradition came to an end. Beset by illness Horst died in 1920.

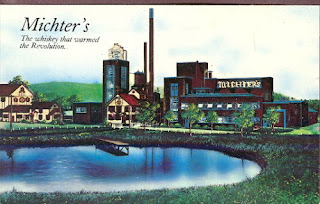

After Repeal, the family sold the distillery to Pennco Distillers, who made whiskey in the facilities the Bombergers built until 1978 when the distillery was sold to the Michter Company who celebrated the Shenk-Bomberger Mennonite tradition in numerous ways, including a postal cover. For a decade Michter successfully promoted the site as a Pennsylvania tourist attraction. The company also issued a whiskey jug and candle holder in the Mennonite tradition, showing a dove of peace and citing the 1753 date to claim being the oldest distillery in America.

After Repeal, the family sold the distillery to Pennco Distillers, who made whiskey in the facilities the Bombergers built until 1978 when the distillery was sold to the Michter Company who celebrated the Shenk-Bomberger Mennonite tradition in numerous ways, including a postal cover. For a decade Michter successfully promoted the site as a Pennsylvania tourist attraction. The company also issued a whiskey jug and candle holder in the Mennonite tradition, showing a dove of peace and citing the 1753 date to claim being the oldest distillery in America. %20.jpg) Michter's went bankrupt in 1989, however, and Abe Bomberger’s distillery, while still standing, since has been unoccupied and for years suffered severe deterioration from lack of maintenance. Bomberger's was listed on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1975, and was declared a National Historical Landmark in 1980. Those designations have resulted in improved efforts at preservation. Although there are whiskey products currently on the market using the Bomberger and Michter brand names, they have no

direct connection to the old distillery.

Michter's went bankrupt in 1989, however, and Abe Bomberger’s distillery, while still standing, since has been unoccupied and for years suffered severe deterioration from lack of maintenance. Bomberger's was listed on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1975, and was declared a National Historical Landmark in 1980. Those designations have resulted in improved efforts at preservation. Although there are whiskey products currently on the market using the Bomberger and Michter brand names, they have no

direct connection to the old distillery.