When the definitive history of American distilling is written, Rufus Mathewson Rose -- whose company gave rise to the familiar “Four Roses” brand whiskey -- will deserve considerable attention. Not the least of his accomplishments were his early use of aggressive advertising and the range of stoneware jugs in which he marketed his products.

When the definitive history of American distilling is written, Rufus Mathewson Rose -- whose company gave rise to the familiar “Four Roses” brand whiskey -- will deserve considerable attention. Not the least of his accomplishments were his early use of aggressive advertising and the range of stoneware jugs in which he marketed his products.Rufus Rose, shown here in maturity, was born in 1836, a Connecticut Yankee with a Puritan pedigree. While studying medicine in New York, he traveled in 1853 to Hawkinsville, Georgia, to help out temporarily in his uncle’s drugstore. He liked the place and the work. In 1858 he moved to Dixie for good and in 1860 opened his own drugstore in Hawkinsville. That same year he married a local girl, Susan Wilcox of Wilcox County.

Sympathetic to the Southern cause in the Civil War, Rose closed his business early in the conflict and despite his medical background enlisted as a foot soldier. In late 1861 he was reassigned by the Confederacy to be a pharmacist and sent to work in Virginia. There his health failed and he was honorably discharged in 1862.

After the Civil War, Rose relocated to Atlanta where about 1867 he organized a whiskey producing enterprise he called “House of Rose.” His knowledge of the chemistry of distilling and business acumen were rewarded with rapid success. He built a large distillery on Stillhouse Road in nearby Vinings and established a retail store for selling whiskey in the downtown Atlanta.

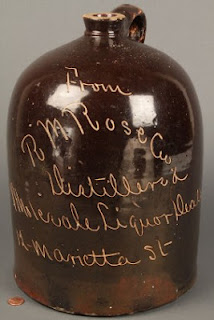

According to one contemporary account, this transplanted Yankee became “very successful, winning a prominent place among Atlanta’s enterprising citizens.” By 1870 as “R.M. Rose Co. Distillers,” Rufus was advertising his products heavily in the Atlanta and other Southern newspapers, touting such blended rye and corn liquor products as “Rose’s Atlanta Spirit Rye,” “Rose’s Mountain Dew, “ “Blue Ridge Whiskey,” “New Sweet Mash,” “Old Reserve Stock” and “Special Old Corn.”

Rose loved being a distiller and had little time for the anti-liquor folks who proclaimed whiskey “the demon’s drink.” He advertised his whiskeys as “...the purest, safest drink you could buy” and claimed that “when used in moderation, its effect on the human system is wholesome and beneficial....”

Rose was a prime customer of many Georgia potters of his time. Howell’s Mills, a pottery center close to Vinings, produced a wide variety of articles for the distillery, large jugs for providing whiskey wholesale to taverns and saloons and smaller containers for direct sales to the public. These stoneware jugs described a broad range of appearance, from beehive shapes and “scratch” jugs to shoulder jugs with overglaze labels. Some had the traditional brown top and beige body, others were covered entirely with brown Albany slip or white Bristol glaze.

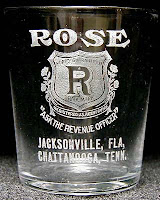

Despite whiskey distilling being a major Southern industry, states below the Mason-Dixon line were prominent among those experimenting with prohibition laws. When Atlanta briefly went “dry” in 1885 Rose moved his offices from his beloved city for two years until it legalized liquor again. During this period Rose also opened an operation in Jacksonville, Florida.

His confidence in being able to continue operations seems expressed in his building a mansion in 1901 for $9,000 on Peachtree Street, then the neighborhood of Atlanta’s elite. Following the fashion of the time, the architecture of the home is Queen Anne-style but it was placed on a narrow lot that gave it a townhouse look. Nonetheless, the Rose mansion was included in the 1903 “Art Works of Atlanta.” The house still stands today and recently was up for sale.

His confidence in being able to continue operations seems expressed in his building a mansion in 1901 for $9,000 on Peachtree Street, then the neighborhood of Atlanta’s elite. Following the fashion of the time, the architecture of the home is Queen Anne-style but it was placed on a narrow lot that gave it a townhouse look. Nonetheless, the Rose mansion was included in the 1903 “Art Works of Atlanta.” The house still stands today and recently was up for sale.After only a few years in his fancy new home, Rose must have been devastated when the State Legislature voted all of Georgia dry in 1907. He shut down the distillery in Vinings and the Atlanta retail outlet. Then R.M. Rose Distillers moved lock, stock and barrels to Chattanooga, Tennessee. A shot glass from that period marks the move.

His funeral, held at his home, was a major event. An Atlanta newspaper reported: “The funeral was one of the largest in point of attendance ever held in Atlanta for a private citizen, the entire first floor of the large resident and the front lawn proving altogether inadequate to accommodate the hosts of friends who gathered to pay the last sad tributes to one who has played an important part in the upbuilding of Atlanta, even though he at all times refused absolutely to permit his name to be used for any public office.” His grave was marked with a sign of his service in the Confederate Army.

A late achievement may also have been Rose’s most lasting. About 1906, according to accounts, he came up with the special blend that he called “Four Roses.” But it was only after Rose Distillery was transplanted to Chattanooga that the name became a synonym for American whiskey throughout the U.S. and eventually the world. By 1914 Four Roses was a national best-selling bourbon.

Almost from the beginning the origin of the Four Roses name has been in dispute. One ad claimed Rufus named the whiskey after his four daughters; but he had only one. Family members believe the four Roses were Rufus himself, son Randolph, brother Origen, and Origen’s son. Another story ties the name to Rose at one time having run four retail establishments. But other records fail to document that number of retail outlets.

Whatever the origins of its most famous brand, the Rose Distillery, relocated in Chattanooga, had little time left. In 1910 Tennessee enacted statewide liquor prohibition. Possibly in frustration, Randolph Rose sold the Four Roses brand name to a whiskey entrepreneur named Paul Jones. Jones moved to Frankfort in still “wet” Kentucky, founded his own distillery, and there built a strong national reputation for the Four Roses name. Eventually the Four Roses brand was purchased by the Seagram Company of Canada which continued to market the bourbon but mainly for export.

Meanwhile, Rufus Rose probably lies happy in the grave knowing that his family name became synonymous with good American whiskey and has been perpetuated around the world.