According census information, Klein, shown here, was born in New York City in 1877, the son of an immigrant mother and father, both of German nationality who had lived in Hungary. How and why Harry migrated to Ohio is unclear but about 1900 he is recorded as operating a saloon and wholesale liquor establishment in Toledo. He issued a half-pint jug given to favored customers of his establishment.

More than a half century before Starbucks was conceived, an enterprising

Columbus, Ohio, whiskey merchant devised a franchise scheme to market his products throughout the Buckeye State by establishing retail outlets in saloons in multiple cities. The merchant was Harry Bayer. The network he created was linked by a single name -- “The Golden Hill.”

Columbus, Ohio, whiskey merchant devised a franchise scheme to market his products throughout the Buckeye State by establishing retail outlets in saloons in multiple cities. The merchant was Harry Bayer. The network he created was linked by a single name -- “The Golden Hill.”

About 1905 Klein, apparently enthusiastic about the concept, joined up with Bayer and changed the name of his establishment to “The Golden Hill Liquor. “ Described in Toledo business directories as a distributor of “wines & brandies & fine whiskies,” the company initially occupied a building in downtown Toledo at the corner of Monroe and Adams Streets, then moved next door to 519-520 Adams Street. To let his customers know of the move, he issued a postcard. On one side, it showed the old business site and the new one, replete with a Golden Hill sign. On the other of the postcard was a small picture of the smiling Harry.

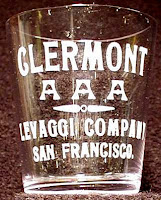

For the next several years Klein seems to have been an energetic participant in the franchise. He may have been provided with some funding by Bayer that allowed him to make the move next door and also to open another outlet on Toledo’s Adams Street. Over the years Klein commissioned and gave away a series of The Golden Hill half-pint and mini-jugs. Given the numbers of these items to be found today, Klein must have distributed hundreds, a possible sign of affluence and success. To saloons and other drinking establishment featuring Golden Hill whiskeys, he also provided metal tip trays.

Whatever dynamic was catapulting Klein and The Golden Hill into prominence in the Buckeye State whiskey trade was short-lived and waning by 1908. That year the Akron Gold Hill outlet apparently shut down. By 1910 Harry Klein apparently had had enough and his Golden Hill establishment disappeared from Toledo business directories. Whether he stayed in the liquor trade, remains unclear. In 1918 Ohio voted in Prohibition and most liquor businesses shut down.

In 1917 Harry emerged as the representative of a Cleveland based company called Central Brass Manufacturing that sold plumbing fixtures and accessories. He is shown below as he attended a convention of the Master Plumbers Assn. Later that same year he was recorded as the leader and manager of a new company called Toledo Store Fixture Company, incorporated with a capitalization of $10,000. That business also seems short-lived. By 1919 the “Credit Men’s Bulletin,” a publication advertising for deadbeat borrowers, had published Harry’s name, looking for his whereabouts.

In 1920 the U.S. Census found Klein still living in Toledo. He was 43, listed as a widower, and residing in Cora McCarthy’s rooming house with a group of other unmarried men and women. His occupation appeared to be peddling brushes from door to door. The slide off the Golden Hill for Harry Klein had been a precipitous one.