never met Freeman -- but that story comes later. First, we should meet whiskey man Abe.

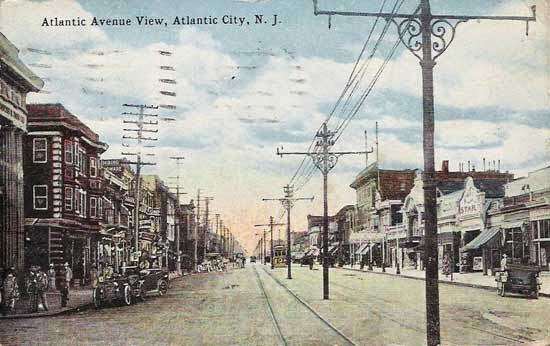

never met Freeman -- but that story comes later. First, we should meet whiskey man Abe. Historical records indicate that Freeman was born in London, England, in 1871, although one census listed him as a native of Germany. His parents were German Jewish émigrés to England, Isaac Freeman (sometimes given as Freedman or Friedman) and Esther (Hester) Altmark. The second of at least three Freeman sons, Abraham emigrated to the United States from England at an early age, likely settling first in Philadelphia. There he met his wife, Rose Meyerhoff and wed her in Philadelphia in 1885. She was the daughter of a German immigrant couple, Raphael (called Robert) Meyerhoff and Julie Isenberg. Abe was 24 and Rose a year younger. By the following year the couple had moved to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where Abe went to work for his father-in-law. Robert Meyerhoff about 1882 had established a liquor business on Atlantic Avenue, the street shown here in an early 1900s postcard.

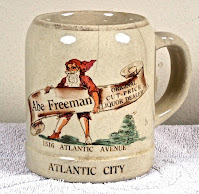

The 1910 U.S. census found the Freemans at home in the Third Ward of Atlantic City with three daughters, Julia, 16; Irma, 14, and Dorothy, 11. Living with the family was the widower Robert Meyerhoff and two servants. Now in his mid-seventies, Meyerhoff by death or design turned the business over to Freeman sometime after 1910. By 1913 Abe was aggressively advertising

“Freeman’s Cut Price Liquor Store.” His price list featured his picture and the assertion that “It Will Pay to Meet Me.” Freeman’s list featured a full line of whiskeys, champagnes,and other wines at “New York Cut Prices.” His case whiskeys included an array of national brands, including Overholt, Green River, Gibson, Clarke, Trimble, Wilson, Gallagher & Burton, and Mt. Vernon. Under Freeman’s management the business prospered. In 1911 he expanded the premises, adding a warehouse and a garage at the rear of his store.

“Freeman’s Cut Price Liquor Store.” His price list featured his picture and the assertion that “It Will Pay to Meet Me.” Freeman’s list featured a full line of whiskeys, champagnes,and other wines at “New York Cut Prices.” His case whiskeys included an array of national brands, including Overholt, Green River, Gibson, Clarke, Trimble, Wilson, Gallagher & Burton, and Mt. Vernon. Under Freeman’s management the business prospered. In 1911 he expanded the premises, adding a warehouse and a garage at the rear of his store.In addition to his retail trade Freeman sold bulk whiskey on a wholesale basis to saloons and restaurants, often providing it in stoneware jugs with cobalt script of his name. He also gave his customers, both wholesale and retail, several varieties

of shot glasses all of them with measuring lines on them and topped with what appears to be a moose or elk head. Since he gave these items

of shot glasses all of them with measuring lines on them and topped with what appears to be a moose or elk head. Since he gave these items  away, he must have been popular with many folks in Atlantic City. But likely not with Mssrs. Brown, Fleming and Sooy.

away, he must have been popular with many folks in Atlantic City. But likely not with Mssrs. Brown, Fleming and Sooy. These three men figured in a bizarre episode in Freeman’s life: While automobiles were not an entirely new conveyance, they were expensive and many people, including Abe, did not own one but he liked “joy riding” with friends around town and the countryside. In 1913 Freeman engaged a vehicle from William Brown who rented out his open touring car for $4 an hour (a whopping $100 in present currency) and provided a chauffeur, in this case Mr. Fleming. Loading the automobile with friends, Freeman jumped into the front seat beside Fleming and they took off. Enroute, a gust of wind blew

the driver’s hat in the air and in an effort to catch it Fleming let go of the wheel momentarily. Seizing the opportunity to drive, Freeman grabbed the steering wheel and swerved the automobile to the side of the road and crashed into a ditch. According to an account given in court: “All the occupants of the car were more or less injured and Fleming sustained a dislocated shoulder.”

the driver’s hat in the air and in an effort to catch it Fleming let go of the wheel momentarily. Seizing the opportunity to drive, Freeman grabbed the steering wheel and swerved the automobile to the side of the road and crashed into a ditch. According to an account given in court: “All the occupants of the car were more or less injured and Fleming sustained a dislocated shoulder.”Freeman’s troubles had just begun. The car was left where it had been ditched and Abe hied off to the nearest inhabited place where he met, likely for the first time, Mr. Sooy. He hired Sooy and some assistants on the spot to remove Brown’s damaged car from the ditch. By the time the party returned to the scene of the accident, it had turned dark. They carried a gas lantern to assist their work, sitting it on the ground to light the scene. As they began to raise the

car an odor of gasoline was detected where it apparently had leaked from the gas tank and soaked into the earth. In an instant the flame from the lantern touched off the fumes and the ground caught fire, spreading quickly to Brown’s expensive automobile. The vehicle swiftly was consumed by flames and rendered a total loss. When Brown sued Freeman for damages, the liquor dealer contended that it was Sooy’s fault and he himself bore no responsibility. The court of first jurisdiction disagreed and told him to pay up. Continuing to object, Freeman appealed the verdict to the New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals. There the result was the same. Sooy was found to be in the employ of Freeman and as the employer Freeman was liable. He paid.

car an odor of gasoline was detected where it apparently had leaked from the gas tank and soaked into the earth. In an instant the flame from the lantern touched off the fumes and the ground caught fire, spreading quickly to Brown’s expensive automobile. The vehicle swiftly was consumed by flames and rendered a total loss. When Brown sued Freeman for damages, the liquor dealer contended that it was Sooy’s fault and he himself bore no responsibility. The court of first jurisdiction disagreed and told him to pay up. Continuing to object, Freeman appealed the verdict to the New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals. There the result was the same. Sooy was found to be in the employ of Freeman and as the employer Freeman was liable. He paid.Still other troubles were ahead. A year later, Federal Food and Drug agents entered Freeman’s 1532 Atlantic Avenue premises and seized 20 cases of “Radio-Active Mountain Valley Water.” Each case contained a dozen green embossed glass bottles. The product, reputedly from Hot Springs,

Arkansas, carried a label claiming to be a remedy for Bright’s (kidney) disease, diabetes, cystitis, and rheumatism. This was a period when nostrum peddlers, taking advantage of public ignorance about radioactivity were pushing such mineral waters as panaceas. In the case of Mountain Valley Water, scientists had determined that patients would have to consume an entire liter at one time to get even a modicum of radioactivity. Moreover, there was no evidence that the water was useful in the treatment of the diseases as claimed. Although Abe Freeman was the distributor, this time the fine of $500 fell on the Mountain Valley Water Company.

Arkansas, carried a label claiming to be a remedy for Bright’s (kidney) disease, diabetes, cystitis, and rheumatism. This was a period when nostrum peddlers, taking advantage of public ignorance about radioactivity were pushing such mineral waters as panaceas. In the case of Mountain Valley Water, scientists had determined that patients would have to consume an entire liter at one time to get even a modicum of radioactivity. Moreover, there was no evidence that the water was useful in the treatment of the diseases as claimed. Although Abe Freeman was the distributor, this time the fine of $500 fell on the Mountain Valley Water Company. In addition to selling Mountain Valley Water, Freeman was the Atlantic City agent for another bottled water called “Clysmic.” This product, which was the self-declared “King of Table Waters,” made no specific therapeutic claims but advertised that it “promotes health, pleases the palate and exhilarates the mind.” Just in case the mind needed additional exhilarating, Clysmic provided customers with a serving tray that depicted a bare breasted, beauty with long tresses sitting in a stream while a deer drinks at her side.

Freeman had a relatively short time to make his mark in the whiskey trade, possibly as brief as seven or eight years after taking over for his father-in-law. Although New Jersey was not a “dry” state, the enactment of National Prohibition meant the end of all liquor sales, even cut rate ones. Abe shut his doors on Atlantic Avenue, never to open them again. Records indicate two dates of death for Freeman. One shows him dying in Atlantic City in 1927; a second in 1948 in Forest Hills, New York.

But the story does not end there. The Freemans’ daughter Irma married a man named Mark Bertram Bacharach, a well-known syndicated newspaper columnist. That couple produced one of the most celebrated American singers, song writers, composers, pianists and record producer of the 20th Century, Burt Freeman Bacharach. Obviously named after Abe, Bacharach, a six time Grammy Award winner and three times Academy Award winner, might or might not have known his grandfather. The song writer was born in 1928, one year after Freeman died according to one record; by another account Bacharach would have been 20 years old and certainly have known Abe Freeman, a man who wanted people to meet him.

I just couldn't have enjoyed this post more. It has it all: obscure whiskey history. Excellent writing and historianship. A stunning act of idiocy. A dramatic turn of events. And a great twist in the end. What a story!

ReplyDeleteDear Joshua: Thanks for your very kind and most appreciated comments. Abe Freeman's was a good story. Some of my best material comes from court cases I find on line when I am researching an individual. Freeman's mishap was a natural. Only as I was wrapping up the research did the Bachrach connection appear. Wish I could have nailed down Abe's death date more precisely but more than an hour of trying did not resolve the conflict and I could not find a gravestone. If I get something authoritative later, the change is easily made. Jack

Delete