On May 29, 1919, seven months and and one day before the imposition of National Prohibition on America, the Boston Globe informed it readers: “Prohibition claims its first victim in Boston today when John Fennell will lock up for all time his long famed wine shop.” The newspaper quoted Fennell opining: “Prohibition is coming and you can’t stop it. It’s coming like a great wave headed for the bow of a ship and its going to break soon. But it’s going to miss me.” Was there something untold behind Fennell’s bravado? The Globe hinted as much.

If Fennell was telling the truth, he was considerably more prescient than most of his fellow whiskey dealers around the country. In most locales going dry, the liquor houses and saloons hung on until the clock chimed midnight on their trade. Some had “fire sales” at the end, steeply discounting their bottles and jugs. Others were left with large supplies of whiskey, always in danger of confiscation by authorities and destroyed. Those stashes might be sent abroad, buried in the cellar or sold under the counter.

Fennell by his forethought seemingly escaped those problematic consequences. But had he? He boasted about register sales of $200,000 in the past several weeks, equivalent to $3.16 million in today’s dollar, saying: “Six weeks ago I said to myself l could never unload my stock by this time. But here I am cleaned out. Not a bottle in the shop.” Yet the Globe reporter clearly had doubts. He noted that some jugs, bottles and “ambrosial liquids” were still visible. “Are the bugs loading up?” he speculated. Was this claim just Irish “blarney”?

Fennell was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1853, according to naturalization records, a date that is confirmed on his gravestone. Arriving in North America in his 20s, the immigrant’s initial destination appears to have been St. John’s, British Columbia. There he went to work for a wholesale liquor and beer dealer named Thomas Furlong, who also appears to have been his brother-in-law. Fennell would work for Furlong for a dozen years learning the liquor trade in Canada. Although I cannot find a photo, a passport described the Irishman standing 5 feet, 6.5 inches tall, with gray eyes, brown hair and tawny skin.

Established in business as early as 1862, Furlong appears to have run a successful enterprise. His flagship brand was “Furlong’s Irish Malt Whiskey.” He advertised it as “celebrated Dublin malt whiskey,” claiming that it rivaled the finest cognac brands: “It has been stored five years in Sherry Casks, and is highly recommended for Medical and other purposes being mellowed with age, PERFECTLY PURE, and free from those heating qualities usually found in other whiskeys.” Apparently this tipple was not meant for frigid Canadian nights.

Established in business as early as 1862, Furlong appears to have run a successful enterprise. His flagship brand was “Furlong’s Irish Malt Whiskey.” He advertised it as “celebrated Dublin malt whiskey,” claiming that it rivaled the finest cognac brands: “It has been stored five years in Sherry Casks, and is highly recommended for Medical and other purposes being mellowed with age, PERFECTLY PURE, and free from those heating qualities usually found in other whiskeys.” Apparently this tipple was not meant for frigid Canadian nights.

Fennell’s familial relationship to Furlong may explain why the Canadian trusted to sent him in March 1879 to open a satellite store in Boston, 1,200 miles from St. John. The Globe recorded his arrival with this notice: “MR. THOMAS FURLONG,” the well known wine merchant of St. John, N. B., has opened a branch of his establishment at 161 Devonshire Street and 22 Arch Street, under the management of Mr. John Fennell, who has been with Mr. Furlong for twelve years, and in whom he reposes every confidence….Mr. Furlong has had experience of twenty-five years in the wine trade, and his selections can be relied upon as of the very best.”

Such a warm welcome from Boston’s currently oldest and largest newspaper loses some of its luster when it is understood that in its early years the Globe largely was controlled by Irish Catholic interests. Moreover, Fennell reciprocated the favor two week later, and often thereafter, with Globe ads for Furlong’s Irish Malt and other alcoholic products.

A quick reading of those ads might leave the impression that the liquor house had two stores. Fennell listed two addresses, 177 Devonshire and 38 Arch Steet, that actually described one building. The liquor store encompassed two rooms, one at ground level where sales took place and a cellar used to store liquor and beer with elevator access. A drawing shows a busy mercantile area with businesses ranging from insurance agents to a telegraph company. Although the street address changed slightly over time Fennell remained at that location for 33 years.

Upon first arriving in Boston Fennell, still a bachelor, found lodging in an Irish-run boarding house on Oak Street. Two years later he reached back to British Columbia to find a bride. She was Mary E. Quinn, at 25 three years younger than John. She had been born in Canada of Irish immigrant parents. John and Mary would have only one child, a son, Frederic J., who died at three years old, a source of heartache in the couple’s lives.

Fennell showed a particular talent for advertising his products in Boston area publications. Here is an example: “PURE WHISKIES – that are stored in sherry wine casks have a mellowness not found in other whiskies, and being honestly aged are free from those heating qualities usually found in so called old goods. Buying all whiskies from the distillery direct, I can sell fine goods from $8 a dozen up to the celebrated O.F.R., costing $30, and ordinary and special, in wood from $8 to $10 per gallon.” Fennell also boasted of his brandies “selected from the leading houses of Cognac” and of personally selecting fine wines during his visits to the wine-producing districts of Europe. He also advertised an imported English ale.

Fennell showed a particular talent for advertising his products in Boston area publications. Here is an example: “PURE WHISKIES – that are stored in sherry wine casks have a mellowness not found in other whiskies, and being honestly aged are free from those heating qualities usually found in so called old goods. Buying all whiskies from the distillery direct, I can sell fine goods from $8 a dozen up to the celebrated O.F.R., costing $30, and ordinary and special, in wood from $8 to $10 per gallon.” Fennell also boasted of his brandies “selected from the leading houses of Cognac” and of personally selecting fine wines during his visits to the wine-producing districts of Europe. He also advertised an imported English ale.

Fennell sold his products in bottles blown in a three piece mold, both in amber and green glass. Shown above are two examples of his quart glass containers, both bearing his name and “Boston.” These bottles also carry “O.G.R.” on the base, a mark that normally denotes the glasshouse that made the bottle. In this case it does not. As shown here in an ad, the initials stand for O. Gordon Rankine, a Boston glassware dealer and jobber who was receiving his bottles from factories in Baltimore and Philadelphia. Rankine apparently insisted on adding his own mark.

Fennell sold his products in bottles blown in a three piece mold, both in amber and green glass. Shown above are two examples of his quart glass containers, both bearing his name and “Boston.” These bottles also carry “O.G.R.” on the base, a mark that normally denotes the glasshouse that made the bottle. In this case it does not. As shown here in an ad, the initials stand for O. Gordon Rankine, a Boston glassware dealer and jobber who was receiving his bottles from factories in Baltimore and Philadelphia. Rankine apparently insisted on adding his own mark.

Although the original paper labels are missing from the great majority of Fennell's bottles, a label for his “Medford Rum” recently has come to light. It is elaborately designed with accents of palm branches and flowers, a trade mark of a black bird rampant on a shield, and most interesting of all, two winged angels. These cherubs are known by the Italian word, “putto” and more usually identified with beer.

After 14 years of Furlong’s ownership, the Canadian turned over the liquor house to Fennell. The change was noted in the October 17, 1886, issue of the Globe. The new owner wrote: “I have, therefore, the pleasure of announcing that I have opened at the old stand, and that in the future the business will be conducted as heretofore, but in my name solely…. I am in the position to give my customers, as in the past, the same pure and reliable goods at reasonable prices.”

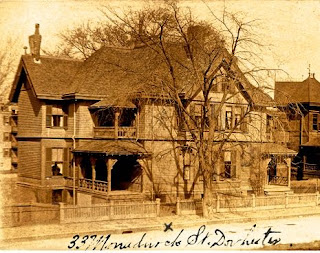

He and Mary also moved into new lodging, renting a house at 33 Monandock Street, an unusual structure divided through the middle into two single-family attached homes and yards, shown here. The 1900 federal census found the couple living there along with Mary’s sister, Kate Quinn. That same year Mary died and was buried in St. Joseph Cemetery, West Roxbury.

The 1910 census found Fennell at a new home address. Living with him and keeping house was his unmarried sister, Mary; a niece Helen, and a female servant. During this period Fennell was traveling frequently to Continental Europe, the British Isles, and Latin America. A prime destination was Cuba with its rum factories. One of the ships on which Fennell traveled, the S.S. Banan, a banana boat, is shown here loading cargo in Cuba.

The 1910 census found Fennell at a new home address. Living with him and keeping house was his unmarried sister, Mary; a niece Helen, and a female servant. During this period Fennell was traveling frequently to Continental Europe, the British Isles, and Latin America. A prime destination was Cuba with its rum factories. One of the ships on which Fennell traveled, the S.S. Banan, a banana boat, is shown here loading cargo in Cuba.

On a ship bound for England to see relatives in 1828 Fennell became seriously ill, seemed to recover after landing, suffered a relapse and died. He was 75 years old. His body was returned to Massachusetts where he was buried next to Mary and Frederic. Despite the Globe reporter’s apparent skepticism about Fennell’s account of his closing, no evidence ever came to light that the Irish whiskey man was fibbing about having sold all his liquor months before the National Prohibition axe fell.

On a ship bound for England to see relatives in 1828 Fennell became seriously ill, seemed to recover after landing, suffered a relapse and died. He was 75 years old. His body was returned to Massachusetts where he was buried next to Mary and Frederic. Despite the Globe reporter’s apparent skepticism about Fennell’s account of his closing, no evidence ever came to light that the Irish whiskey man was fibbing about having sold all his liquor months before the National Prohibition axe fell.

Note: This post was occasioned by the recent find of the “Medford Rum” bottle by collector Peter Samuelson of New Hampshire. It encouraged me to research information on Fennell. Fortunately an internet blog entitled “Mike’s Glass Bottle Collection and History” (https://baybottles.com) provided a wealth of material on Fennell, including the Boston Globe articles and two Fennell ads.

No comments:

Post a Comment