Arguably, the most important figure in the history of American distilling was Col Edmund H. Taylor Jr. of Kentucky. During his 92 years (1830-1923) Col. Taylor came to epitomize the whiskey industry and became its chief spokesman to American presidents, the U.S. Congress and other high government officials. Because he insisted that his portrait and signature be prominent on all his products, it is possible to track Taylor’s career through his changing public face.

The earliest picture I can find of Col. Taylor is from a trade card early in his career, a time of trial. It is the face of a early middle aged man considered a rising star in Kentucky distilling. Taylor, however, was squeezed financially in the Panic of 1873 and resorted to fraud, reported selling rights to 7,014 barrels of whiskey when only 4,722 barrels were aging in his warehouse. Exposed and owing the equivalent of $11 million in current dollars, Taylor was bailed out by rival George Stagg who took over his distilleries and relegated him to being a hired hand.

The earliest picture I can find of Col. Taylor is from a trade card early in his career, a time of trial. It is the face of a early middle aged man considered a rising star in Kentucky distilling. Taylor, however, was squeezed financially in the Panic of 1873 and resorted to fraud, reported selling rights to 7,014 barrels of whiskey when only 4,722 barrels were aging in his warehouse. Exposed and owing the equivalent of $11 million in current dollars, Taylor was bailed out by rival George Stagg who took over his distilleries and relegated him to being a hired hand.

Eventually paying off his debts, Taylor broke from Stagg and with his sons, built a new distillery he called “The Old Taylor Distillery Co.” in Frankfort, Kentucky. By this period, the Colonel had donned spectacles and assumed the chastened look of someone who has “learned his lesson” and was seeking to regain legitimacy among his peers. This likeness eventually would find its way onto an advertising watch fob and to the sides of cases of his straight Kentucky whiskey.

Taylor’s return to “whiskey baron” status inevitably brought him into conflict with Stagg who had kept Taylor’s name because of its stellar reputation for bourbon. When the Taylors opened their new facility, Stagg sued to stop them using their family name on their whiskey. Over the next months, a legal battle was waged that ended in the Kentucky Supreme Court with a partial victory for the Taylors. They could continue to use “Old Taylor,” but Stagg’s “Taylor” products were still allowed on the market. Thus the emphasis emerged on using the Colonel’s face and signature to proclaim the “genuine” bourbon. Shown here is a 1903 ad in the Wine and Spirit Bulletin declaring that only the real “Old Taylor” would carry the Colonel’s picture and script.

Taylor’s return to “whiskey baron” status inevitably brought him into conflict with Stagg who had kept Taylor’s name because of its stellar reputation for bourbon. When the Taylors opened their new facility, Stagg sued to stop them using their family name on their whiskey. Over the next months, a legal battle was waged that ended in the Kentucky Supreme Court with a partial victory for the Taylors. They could continue to use “Old Taylor,” but Stagg’s “Taylor” products were still allowed on the market. Thus the emphasis emerged on using the Colonel’s face and signature to proclaim the “genuine” bourbon. Shown here is a 1903 ad in the Wine and Spirit Bulletin declaring that only the real “Old Taylor” would carry the Colonel’s picture and script.

This introduced the era of Taylor’s aggressive look. Characterized as “hard to get along with” and often “downright cantankerous and hard-nosed,” the distiller in this photo clearly is making a statement, squinting his eyes at the photographer and turning his mouth downward. He was now at the top tier of Kentucky distillers and not to be trifled with. This photo later would be translated into a digital image only slightly less intimidating.

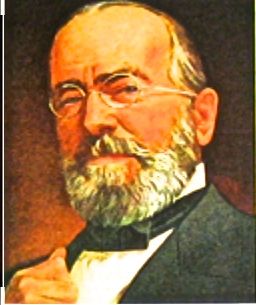

Taylor also was having an impact in Washington, D.C. A friend of the Secretary of Agriculture, Kentuckian John Carlyle, he played a major role in the shaping and passage of the “Bottled in Bond Act of 1897” and later in gaining support for passage of the first Food and Drugs Act. He was lobbying Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and later William Howard Taft to declare blended whiskeys as “artificial,” a battle he ultimately lost. The Colonel Taylor shown here may reflect the demeanor of “respectful persuasion” he likely adopted when visiting the Nation’s Capitol.

Taylor also was having an impact in Washington, D.C. A friend of the Secretary of Agriculture, Kentuckian John Carlyle, he played a major role in the shaping and passage of the “Bottled in Bond Act of 1897” and later in gaining support for passage of the first Food and Drugs Act. He was lobbying Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and later William Howard Taft to declare blended whiskeys as “artificial,” a battle he ultimately lost. The Colonel Taylor shown here may reflect the demeanor of “respectful persuasion” he likely adopted when visiting the Nation’s Capitol.

As he approached an advanced age, a clear effort was made to sweeten Taylor’s image. In the photo here, his mouth is turned down but the squint is gone. In formal dress, the white bowtie softens his physiognomy. Here Taylor seems to be telling us he is “The Elder Statesman” of the liquor industry. His company used a similar photo on a paperweight.

As he approached an advanced age, a clear effort was made to sweeten Taylor’s image. In the photo here, his mouth is turned down but the squint is gone. In formal dress, the white bowtie softens his physiognomy. Here Taylor seems to be telling us he is “The Elder Statesman” of the liquor industry. His company used a similar photo on a paperweight.

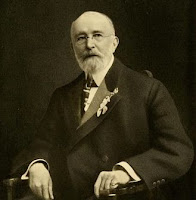

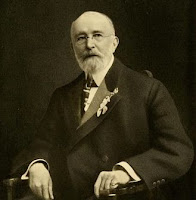

Another late photo also emphasizes a more benign temperament for Taylor. He has been though a lifetime of struggles and surmounted them them all to emerged in his “golden years” respected by his peers and listened to by people in high places. The flower in his button hole, likely lily-of-the-valley, bespeaks banking of a fiery temperament in favor of a gentle glide into old age.

Another late photo also emphasizes a more benign temperament for Taylor. He has been though a lifetime of struggles and surmounted them them all to emerged in his “golden years” respected by his peers and listened to by people in high places. The flower in his button hole, likely lily-of-the-valley, bespeaks banking of a fiery temperament in favor of a gentle glide into old age.

Even in death, however, Colonel Taylor could not escape reproductions. Shown here is a plaque at the present day Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort. it commemorates the O.F.C. (Old Fashioned Copper) Distillery founded by Taylor in 1870. The face on the metal sign clearly is taken from the “aggressive” Taylor of late middle age. It even reproduces Taylor’s necktie. If possible, it is even more baleful a look than the original.

Even in death, however, Colonel Taylor could not escape reproductions. Shown here is a plaque at the present day Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort. it commemorates the O.F.C. (Old Fashioned Copper) Distillery founded by Taylor in 1870. The face on the metal sign clearly is taken from the “aggressive” Taylor of late middle age. It even reproduces Taylor’s necktie. If possible, it is even more baleful a look than the original.

A final look at Edmund H. Taylor, Jr., was provided in a post-Prohibition Christmas advertisement for Old Taylor Bourbon. The theme is that while the distiller was usually hard to get along with, at the holidays a genial Taylor “gathered his loyal employees around him, and as the bottle of Old Taylor passed among them, he.d tell them, one by one how much he had appreciated all they had done. And he’d allow himself a small smile of satisfaction.” Presumably the portrait of Taylor shows that “small smile.” My thought is that the distiller’s satisfaction instead may stem from being able to satisfy his staff with a swallow of liquor and skip Christmas bonuses.

No comments:

Post a Comment