Edward Kolb was born in Monroe, Wisconsin, in September 1863, the son of Emma and Abtaham Kolb. His father, an immigrant from Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany, moved to San Francisco about 1869. There the boy early was introduced to the German Turnverein athletics where he demonstrated superior ability at gymnastics but soon caught wider attention as a highly talented wrestler.

In those days wrestling styles were classified two ways: Greco-Roman, the Olympic style, dictates that the legs may not be used in any way to obtain a fall, and no holds may be taken below the waist. Catch-as-catch-can is free style wrestling in which nearly all holds and tactics are permitted in both upright and ground wrestling. Rules forbid only actions that may injure an opponent, such as strangling, kicking, gouging, and hitting with a closed fist. Kolb was a master at both styles. He held the Pacific Coast Middle-Weight Amateur Championship from 1885 until 1890.

Perhaps Kolb’s most notable victory occurred in 1888 was when he met the heavyweight champion of the West Coast, a wrestler named Pritchard. After tussling for two hours without either man gaining a fall, the match was postponed for a month. At the rematch, Kolb won in two straight falls. Another well-publicized win was in April 1990 when he defeated Al Lean, leading to Kolb being crowned overall champion of the West Coast.

|

| Honored as Referee |

That victory was not without controversy. An investigation into wrestling practices by California officials heard testimony from a wrestler named Gus Ungerman who claimed he knew enough about cheating in amateur wrestling “to fill a book.” He told investigators that he thought the Kolb-Lean match was a “fake,” implying that Lean threw it. Whether it was this allegation or for other reasons, Kolb’s active career in wrestling ended soon after, but he continued as a respected referee.

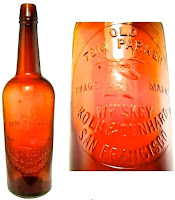

The same year as his marriage to Emma, Kolb teamed with her brother, Herman Denhard, to open a liquor store. Ed had learned the whiskey and wine trade working in the storage cellars of Kohler & Van Bergen [see post on Van Bergen, Nov. 1, 2020]. As shown by the trade card above, Kolb & Denhard featured a wide range of imported and domestic wines, liquors and mineral waters at their 422 Montgomery Street address, shown below. That is Kolb standing at the left side of the photo, staring into the camera.

By all accounts the Kolb & Denard liquor house was a rousing success. So much did his business thrive that when Kohler & Van Bergen left their original premises, Kolb, said to be fulfilling a youthful ambition, moved to that location. Said the San Francisco Call newspaper of of Kolb: “He…built up a big business by his untiring energy and by his big warmhearted manner.”

In 1903, according to press accounts, Kolb: “…suffered a nervous collapse, brought on by too close application to business. Although he abandoned the active life to which he had been accustomed,the rest did not bring him the wished for relief.” With his liquor business now being carried out by associates, Kolb sought respite in the quiet of the family’s country house in Palo Alto, 33 miles south of San Francisco. Nothing, however, seemed to ease his mental torment.

Notes: I was drawn to the story of Edward Kolb by seeing examples of his company’s whiskey bottles from the Ken Schwartz collection in the “Virtual Museum” of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). That led me to other sources, including Kolb’s extensive obituary in the San Francisco Call of Jan. 23, 1904. Several online sources filled in the whiskey man’s stellar wrestling career.

No comments:

Post a Comment