|

| S.T. Suit |

Whiskey baron Samuel Taylor (S. T.) Suit whose distillery and mansion sat in what is now Suitland, Maryland, adjacent to the District of Columbia, was an early example of a “Washington insider,” wining and dining Presidents, members of Congress, and high Executive Branch officials. Although a past post (see August 4, 2011) described Suit’s life and loves in detail, one event in which he played a pivotal role was omitted. Suit was responsible for the venue of negotiations that helped settle a prolonged legal battle between the United States and England in the wake of the Civil War.

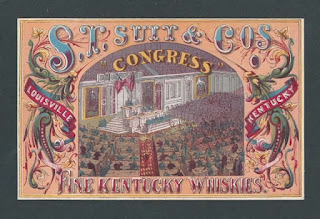

Throughout his career Suit was a man with a keen eye for political clout and ingratiated himself with the power brokers of his time. Colorful trade cards for his whiskey focussed on of Washington, D.C. One shown here speaks of “fine Kentucky whiskey,” but shows the U.S. Capitol, including the back of a toga clad George Washington statue that once stood there. Suit used a second view of the Capital as his letterhead and on ads.

Suit matched them with two colorful trade cards of the U.S. Congress in session, Senate and House of Representatives, looking much as they did in his time. It may be assumed that Suit himself frequently was in the gallery or to be found chatting in the members’ lobbies.

The Maryland distiller did not come empty handed to the Congress and Suit’s whiskey containers were said to be a frequent sight in the U.S. Capitol. His gifting made him a welcome figure in those hallowed halls. He also made sure his whiskey was sold in the finest Washington D.C. hotels where many senators and congressmen spent their leisure hours.

Suit’s push for influence in the Nation’s Capital paid off in several ways. One trade card provided testimonials for the strength and purity of his whiskey from two District of Columbia officials, the president of the DC Board of Health and an Health Department medical officer. The latter asserted: “Physicians will appreciate how important it is to their success in the treatment of diseases, as well as to the patient, that the stimulants they prescribe should be of a standard and unvarying quality, which desideratum Col. Suit’s liquors appear to fill.”

The canny distiller also used his influence to convince federal officials to built a road from Washington to his estate, known today as Suitland Parkway, and he lobbied successfully for a U.S. post office to be authorized for Suitland when it was largely a rural community and had few residents. Suit’s lavish entertainment of top government officials, including Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes, frequently was noted in Washington newspapers. Likely it was this hospitality that caused Suit’s mansion to be chosen for the conduct of the most sensitive negotiations with England since the War of 1812.

The dispute concerned warships built in Britain and sold to the Confederacy during the Civil War. Although the British Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819 had forbidden the construction of foreign warships, the South was still able to evade the letter of the law and purchase a number of cruisers from Britain. Confederate warships destroyed or captured more than 250 American merchant ships and caused their owners to covert 700 more vessels to foreign flags. By the end of the war, the U.S. Merchant Marine had lost half its ships.

The most famous of those marauding vessels was the CSS Alabama, shown above left being sunk in battle by the USS Kearsarge Before its end, however, the Alabama had done significant damage to the American merchant fleet. Less famous was the CSS Florida, right, that attacked Yankee ships in the South Atlantic until it was captured and disabled off the coast of Brazil. Both vessels figured importantly in the legal wrangling.

Powerful forces in Washington howled for retribution in what became known as “The Alabama Claims.” Senator Charles Sumner, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, wanted $2 billion in damages ($50 billion in today’s dollar), or alternatively, the ceding of all Canada to the United States. Secretary of State Seward was more generous. He suggested the U.S. being given only British Columbia. Other important Yankees coveted Nova Scotia as compensation. Those became known as “indirect claims.” Translation: Not money, just lots of territory.

Public and Congressional fervor over annexing parts of Canada caused the British to stall negotiations for many months after the end of hostilities. Finally in 1870 President Ulysses S. Grant sought to end the dispute through diplomatic talks. To save face, the Washington powers insisted that an initial agreement had to be negotiated on U.S. soil. But where? Grant apparently remembered Suit’s ample food and drink, including his excellent whiskey, and decided that the Suitland estate in nearby Maryland was just the place for American and British diplomats to hammer out the details, as depicted below.

Public and Congressional fervor over annexing parts of Canada caused the British to stall negotiations for many months after the end of hostilities. Finally in 1870 President Ulysses S. Grant sought to end the dispute through diplomatic talks. To save face, the Washington powers insisted that an initial agreement had to be negotiated on U.S. soil. But where? Grant apparently remembered Suit’s ample food and drink, including his excellent whiskey, and decided that the Suitland estate in nearby Maryland was just the place for American and British diplomats to hammer out the details, as depicted below.

Suit himself apparently was delighted with the choice of his home and played genial host throughout the deliberations. He also insured that his whiskey was readily available to help “lubricate” the discussions. The resulting agreement became known as the Treaty of Washington. A sticking point, however, continued to be the lust for all or part of Canada by important American political figures. When the deliberations also failed to settle the amount of recompense for damage to American ships, the two sides agreed to referring monetary compensation to an international third party tribunal, thus breaking new ground in international dispute resolution.

|

| Negotiating the Treaty of Washington |

The British, however, strongly refused to recognize the validity of territorial demands. The dispute remained unsettled until 1871,when the “Alabama claims” at last was referred to an arbitration tribunal convened in Geneva, Switzerland. The international arbitrators threw out the so-called “indirect” claims and awarded the United States $15.5 million for verifiable losses to shipping caused by the Confederate warships. The British, knowing a good deal when they saw it, quickly agreed to pay up. Adjusted for inflation, the settlement would be the equivalent of $400 million today.

The highly popular American magazine, Harper’s Weekly, ran a front page cartoon of the Geneva proceedings, indicating disappointment that the award had not been larger. Uncle Sam is shown addressing the tribunal of judges, pictured as a group of overweight and seemingly distracted Europeans. The symbol of America clearly is disappointed with the outcome, warning the judges that the precedent set by their decision might be used to American advantage in the future: "Sour grapes" are barely disguised.

|

| The Geneva Tribunal |

S.T. Suit, the Washington insider, had etched his name in the history books. Sadly his mansion burned to the ground several years later and was never rebuilt. The Treaty of Washington, it should be noted, has been cited by legal scholars during ensuing years as establishing the principle of third party arbitration, fostering international law and a precursor to the Hague Convention, the World Court and even the United Nations.

No comments:

Post a Comment