John O’Neil was a liquor dealer in Whitehall, New York, doing a thriving mail trade into neighboring Vermont. In December 1882,in what is often referred to as “The Jug Case,” O’Neil was convicted in Vermont on 307 counts of selling whiskey by mai and shipping it from New York to Vermont, contrary to Vermont’s prohibition law. He was given a severe fine and sentenced to hard labor for 19,914 days (54 Years) if the fine was not paid by a specific date.

John O’Neil was a liquor dealer in Whitehall, New York, doing a thriving mail trade into neighboring Vermont. In December 1882,in what is often referred to as “The Jug Case,” O’Neil was convicted in Vermont on 307 counts of selling whiskey by mai and shipping it from New York to Vermont, contrary to Vermont’s prohibition law. He was given a severe fine and sentenced to hard labor for 19,914 days (54 Years) if the fine was not paid by a specific date. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and dragged on for almost ten years. In the end O’Neil paid a smaller fine and may have spent some time behind bars. Writing about O’Neil’s legal woes in Vermont courts, the distinguished American legal scholar Alan Westin wrote: “In any event, whether he broke Vermont granite for decades or became a pioneer father of California, O’Neil’s place in American constitutional history is secure.”

Born in Vermont, O’Neil was the son of Irish immigrants, Edward and Mary O’Neil. According to 1870 census data, his father was a laborer as was John at age 18. Three years later the youth wed Anna M. Conline, both 21. They would have two children, John James and Louis. His new role as a family man likely triggered O’Neil’s changing occupations, moving a few miles south across the Vermont border to own and operate a liquor store in Whitehall, New York.

O’Neil had a sense of the artistic for his liquor containers. Buying his whiskey by the barrel, he decanted it into ceramic jugs of varying sizes for sale. As many Eastern dealers, he preferred to market containers that bore labels in cobalt hand applied script, bearing his name and often the city. (One, top left, recently sold for $475.) O’Neil also offered a line of beers, advertising as a bottler of Schlitz and employing clear blob-top bottles as containers.

Meanwhile Vermont legislators, taking their lead from Dow and the WCTU, voted to make the entire state “dry,” banning the production and sale of all alcohol, except for Communion wine and medicinal purposes. Subsequently put to a public vote the ban prevailed 22,315 to 21,794, a margin of only 521 votes statewide. Meanwhile in Whitehall, O’Neil was neither making or selling whiskey in Vermont, but his sales there were booming, protected, he apparently believed, by the process. It worked this way: O’Neil would receive orders from Vermont through the railroad. The orders came on cards with a Vermont address and the order attached to a jug. In Whitehall, O’Neil would fill the jug, pack it, and send it back to the addressee by rail with a bill for “cash on delivery” The money was collected by railroad personnel and returned to the O’Neil in New York.

In Vermont, however, customs officials and state police were on alert. It had been noted that liquor supplies coming from New York had increased substantially despite all efforts to control them. In 1882 a complaint was lodged against O’Neil fueling an investigation. He was charged with 475 offenses in trafficking liquor and wine into Rutland, Vermont. A trial was held at the Rutland Courthouse, a supreme irony: Rutland was the place of O’Neil’s birth, he considered it his home town, and many years later he would be buried there.

|

| Rutland Courthouse |

Although O’Neil essentially had only been charged with a single count of a jug being sent into Rutland, a local judge and jury through some dubious reasoning and fanciful mathematics sentenced him on 307 counts of violating Vermont’s prohibition law. O’Neil was fined $6,140 dollars (more than $200,000 in today’s dollar) and sentenced to 19,914 days of hard labor (54 years) if the fine was not paid by a given date. The threatened punishment was in excess of sentences for much more serious crimes including armed robbery, forgery and manslaughter.

|

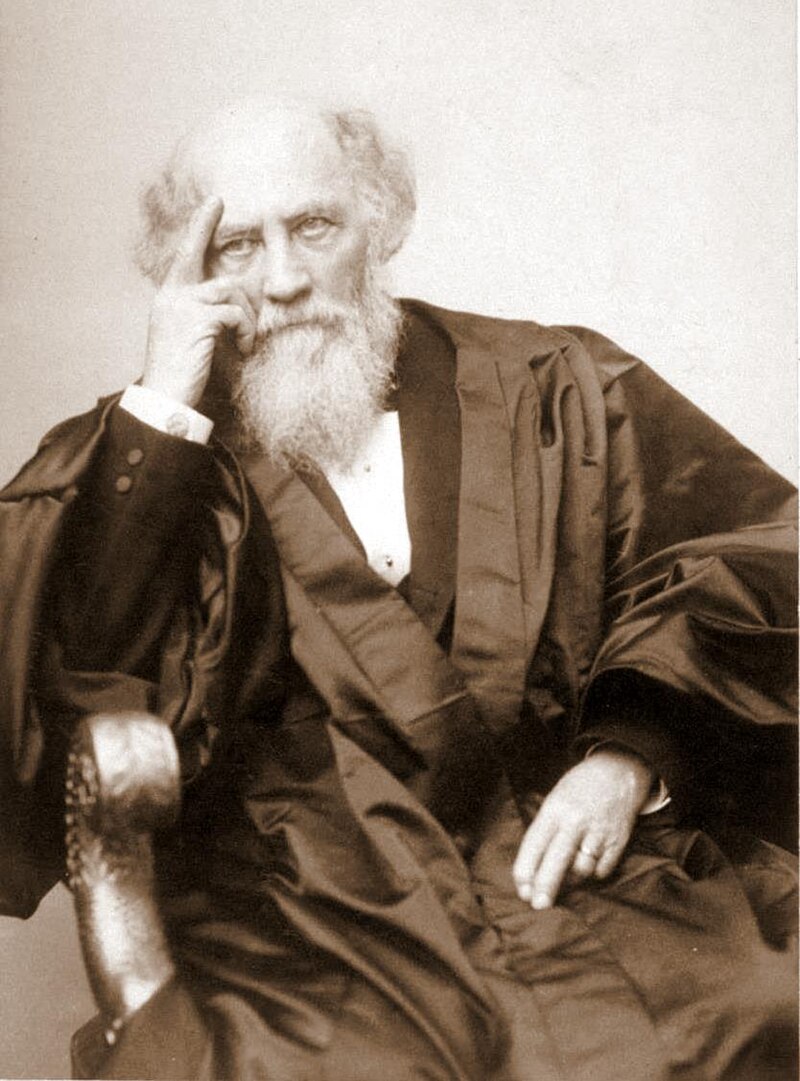

| Chief Justice Blatchford |

Over the next six years O’Neil appealed his case through the Vermont court system all the way to the United State Supreme Court. Although the matter reached the High Court in 1889, the justices did not rule until almost another three years had elapsed. Then, in an opinion written by Chief Justice Samuel Blatchford, the Court majority decided that it lacked jurisdiction to rule against Vermont and in effect let the draconian verdict stand.

|

| Justice Field |

The majority decision, however, did not go unchallenged by a court minority. In a dissenting opinion, Justice Steven Johnson Field, joined by two other justices, took strong objection to the majority opinion. Shown here, Field wrote: “The punishment imposed was one exceeding in severity, considering the offenses of which the defendant was convicted, anything which I have been able to find in the records of our courts for the present century…. Had he been found guilty of burglary or highway robbery, he would have received less punishment than for the offenses of which he was convicted. It was six times as great as any court in Vermont could have imposed for manslaughter, forgery, or perjury. It was Field which, in its severity, considering the offenses of which he was convicted, may justly be termed both 'unusual and cruel.’

Field continued: “The state has the power to inflict personal chastisement, by directing whipping for petty offenses,—repulsive as such mode of punishment is,—and should it, for each offense, inflict 20 stripes, it might not be considered, as applied to a single offense, a severe punishment, but yet, if there had been 307 offenses committed, the number of which the defendant was convicted in this case, and 6,140 stripes were to be inflicted for these accumulated offenses, the judgment of mankind would be that the punishment was not only an unusual, but a cruel one, and a cry of horror would rise from every civilized and Christian community of the country against it.”

In reality, O’Neil’s chances of appeal having been exhausted, he faced an order in 1894 committing him to the House of Correction in Rutland for one month (some accounts say two) and ordered to pay more than $6,000 in fines and court costs. Because the prison records subsequently were destroyed by fire, there is no way of knowing how much time O’Neil actually served. It can be assumed he paid the heavy fine. During ensuing years Vermont’s liquor laws themselves loosened. After another referendum, the state in 1903 restored “local option.”

As proclaimed by Alan Westin above, John O’Neil indeed had written his name in American judicial history — to his personal peril. He subsequently returned to a more normal life in Whitehall, residing at 21 Canal Street. The 1900 census found him there, 48 years old, with wife Annie. His occupation was given as owner of a “combination store,” perhaps indicating some expansion of his inventory beyond liquor and beer.

By the time of the 1915 New York State census, O’Neil had retired. The much persecuted liquor dealer lived to be 77 years old, long enough to see National Prohibition imposed, prove to be a disaster, and repealed. Having sufffered a fatal stroke in 1935, O’Neil was buried in the family plot in Calvary Cemetery. Ironically the site was in Rutland, Vermont — focal point of all the whiskey man’s troubles. Wife Annie had preceded him there by 22 years, dying in 1913.

Note: Much has been written about the case of O’Neil vs. State of Vermont, leaving an almost decade long record of trials and judicial opinions ranging from a Rutland justice of the peace to United States Supreme Court Justices, followed by multiple opinions from Constitutional scholars. It continues to be an excellent example of judicial overreach. The post, however, lacks a photo O’Neil. I am hoping that some alert descendant will remedy that omission.

No comments:

Post a Comment