Foreword: Readers of this blog are aware that from time to time I feature other writers who treat similar subjects. Recently I was researching Baltimore’s Stewart Distillery when I came across an Internet article on that subject by Mike Cavanaugh, a resident of Long Island, New York, and ask his permission to reprint it. He graciously agreed. Mike’s blog, baybottles.com, features some 300 posts. I am pleased to bring his excellent research and information to a new audience and recommend his website.

Foreword: Readers of this blog are aware that from time to time I feature other writers who treat similar subjects. Recently I was researching Baltimore’s Stewart Distillery when I came across an Internet article on that subject by Mike Cavanaugh, a resident of Long Island, New York, and ask his permission to reprint it. He graciously agreed. Mike’s blog, baybottles.com, features some 300 posts. I am pleased to bring his excellent research and information to a new audience and recommend his website.

The Stewart Distilling Company was in business from 1909 until the mid-1920’s but the company’s roots date back much earlier to an Irish immigrant named Robert Stewart. According to 1900 census records, Stewart was born in 1836 in County Antrim, Ireland and immigrated to the United States in 1854. His July 10, 1901 obituary in the Baltimore Sun stated: When a lad of 18 years he came to this country and settled in Baltimore. In 1886 he started a distillery in Highlandtown.

Between 1887 and 1894 Robert Stewart was listed with the occupation “distiller” in the Baltimore city directories. His distillery was located at the southeast corner of Bank and 5th and the office was at 32 S Holliday. In 1894 his business incorporated under the name “Robert Stewart Distilling Company” The incorporation notice was printed in the January 15, 1894 edition of the Baltimore Sun:

Certificate of the incorporation of the Robert Stewart Distilling Company was put on record in the clerk’s office at Towson. The company is formed to continue the distilling business already established by Robert Stewart at Canton. The capital stock is $125,000, in shares of $100 each, and the directors are Robert Stewart, Benjamin Bell, Isaac W. Mohier, Jr., Diedrich Wischhusen and Thos. W. Donaldson.

During this period, the distillery produced a whiskey called “Robert Stewart Rye.” Their agent, at least in New York, was the well established firm of H.B. Kirk who included their brand in several of their advertisements between 1893 and 1895. This December 6, 1893 advertisement in the New York Times stated that it was “bottled at the distillery,” and referred to it as the “Best Eastern Rye.”

Robert Stewart continued to run the business until December, 1897 when he sold the business and retired. The December 31, 1897 edition of the Baltimore Sun ran a story announcing the sale.

A Highlandtown Distillery Sold

The Robert Stewart Distilling Company have transferred to Daniel H. Carstairs and J. Haseltine Carstairs, of Philadelphia, the plant and equipment of their distilling business and three lots of ground on Bank Street and Eastern Avenue. The price paid is not stated. A mortgage for $40,000 for part of the purchase money has been given.

Another story, this one in the January 14, 1898 edition of the Baltimore Sun provided some additional information: The distillery has a capacity of 1,200 or 1,500 gallons of whisky daily, which will be increased to about 3,000 gallons daily by an addition to the plant now in course of construction.

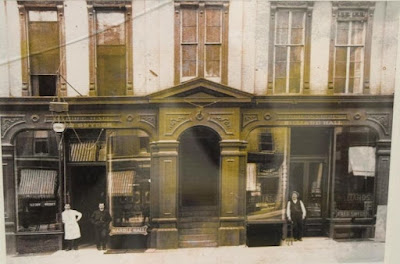

The Carstairs Brothers served as proprietors of the distillery between 1898 and 1908 which was still listed at Bank and 5th in the Baltimore directories. Many of their early 1900’s advertisements included an aerial view of the distillery, which I assume by this time included the additions mentioned in the 1898 story above.

At the same time the Carstairs Brothers were managing the distillery they were also managing the firm of Carstairs, McCall & Co., a business that their family had been connected with as far back as the late 1700’s. Headquartered in Philadelphia, the company was heavily involved in the wine and liquor trade as importers, exporters and wholesale dealers.

A story on Carstairs & McCall in the October 6, 1908 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer described the early history of the business: The present firm style was adopted in 1867, in which year the late James Carstairs and John C. McCall associated themselves as general partners. They were both recognized as imminently enterprising and progressive men of affairs, and under their aggressive management the interests of the house were considerably broadened and extended. The death of Mr. Carstairs, in 1893, was followed by that of Mr. McCall, in 1894, since which time the business has been conducted under the management of Messrs. Daniel H. Carstairs and J. Haseltine Carstairs, sons of the late James Carstairs, who entered the firm in 1885, and representatives of the fourth generation of the Carstairs family in continuous connection with the house.

The Philadelphia headquarters of the firm were located at 222 South Front Street for many years, but were removed in September, 1904, to the commodious and modernly equipped four-story and basement double building now occupied at 254-256 South Third Street. New York offices are maintained in the Park Row Building.

The story went on to say that while the distillery of the firm was located in Highlandtown, the business was done altogether in Philadelphia. This leads me to believe that while they may have been separate business entities, Carstairs Brothers and Carstairs & McCall were in effect operating as one. During this period they called their whisky “Stewart” Pure Rye Whisky.” A January 12, 1905 item printed in the “Wine & Spirit Bulletin” described it like this:

Carstairs Bros. – A Fine Whisky

The absolutely essential elements for a fine blending whisky are a heavy body and strong character and flavor. The same characteristics are equally attractive, after proper aging, in a fine bar whisky. Among the best in this line either for blending or bar use or for bottling in bond is the “Stewart” pure rye whisky, made by Carstairs Brothers, of Philadelphia Pa., at their distillery at Highlandtown, a suburb of Baltimore Md.

The Carstairs Brothers are gentlemen of a remarkably high order of intelligence and ability and character. They, as well as their goods, are thoroughly reliable, which fact will be attested by the trade at large wherever they have had dealings and that covers nearly every section of the country where fine rye whiskies predominate.

The 1908 Philadelphia Inquirer story called Stewart Pure Rye Whiskey their oldest and most well known product and demonstrated that it had grown quite a bit since being acquired by Carstairs: It has a production of over 15,000 barrels per year and is sold all over the United States. A market for it abroad has rapidly increased of late years and many barrels are forwarded to London, Paris and Bremen every year.

Sometime in early 1909 a newly formed company called the Stewart Distilling Company was incorporated in Pennsylvania to consolidate the operation of Carstairs Brothers’ Stewart Distillery and the business of Carstairs, McCall & Co. A story in the April 25, 1909 edition of the Baltimore Sun covered the new corporation’s acquisition of the distillery:

The Stewart Distilling Company, of Pennsylvania, has purchased from Messers. Daniel H. Carstairs and J Haseltine Carstairs, of Philadelphia, trading as Carstairs Brothers, the distillery at Highlandtown, located on Eastern Avenue and Bank Street. The conveyance was recorded yesterday at Towson. The deed transfers 13 lots, 10 in fee and 3 leasehold: also the entire plant, machinery, tools, etc., office fixtures, furniture, whisky brands and trademarks known as “Stewart” brands, formerly owned by the Robert Stewart Distilling Company.

Four days later the Philadelphia Inquirer covered the acquisition of the facilities owned by Carstairs, McCall & Co.: The two buildings at 254-56 South Third Street have been conveyed by J Haseltine Carstairs to the Stewart Distilling Company for a consideration recited as nominal. On a combined lot 50.10 x 180 feet the buildings are four-story brick structures assessed at $30,000.

The new corporation remained under control of the Carstairs brothers with Daniel serving as president and J. Haseltine serving as vice president and treasurer. The company remained listed at the former Carstairs, McCall & Co., South Third Street address through 1918, changing their Philadelphia address to 301 Bellevue Court Blvd. in 1919. In New York their address was listed as 21 Park Row in 1909 and 1910 and 2 Rector Street from 1911 to 1919.

The brand I see advertised the most during this period was called “Carstairs Rye.” A series of advertisements printed in several of the NYC newspapers over the course of 1911 mention that its “the oldest American Whiskey,” dating back to 1788, which is certainly a reference to the first generation of Carstairs. A labeled bottle found on the internet confirms that they continued to produce the Stewart brand as well, now called “Stewart Pure Old Rye”

By 1921 the Stewart Distilling Company was no longer listed in Philadelphia but the distillery in Baltimore survived for several more years. On April 22, 1919, a “liquidation sale” was held at the distillery to dispose of the entire plant, including real estate and equipment as well as the trade name of “Stewart Pure Rye.” Notices announcing the sale were printed in several April editions of the Baltimore Sun.

The day after the sale a story in the Baltimore Sun announced that J. Haseltine Carstairs had purchased the plant in an effort to protect his own interests.

Philadelphian Buys Plant to Protect Interests

J. H. Carstairs, of Philadelphia, was the purchaser of the plant of the Stewart Distilling Company, Eastern Avenue and Fifth Street, at Highlandtown, at public auction yesterday afternoon for a consideration said to have been $125,000. The property has said to have been acquired by Mr. Carstairs to protect his own interest, the transfer involving no immediate solution to the future of the big plant. The property includes four blocks of ground, with nine bonded and free warehouses, , besides the equipment, and is said to have been appraised at $1,150,000 before adverse legislation closed its doors.

Edward Brooks, Jr. attorney for the Stewart Company, said yesterday that after July 1, should the Prohibition law go into effect, a portion of the floor space will continue to be devoted to the storage of liquor now on hand. It is possible, he said, that the remaining buildings will be torn down to make room for improvements for some other line of business.

Sometime in 1921 it appears that the business was reorganized and the Carstairs were no longer involved. In 1922, the Stewart Distilling Company was listed in the Baltimore directories with Arthur Benhoff named as president. A year later in 1923, Robert Pennington and Vincent Flacomio were listed as president and secretary-treasurer respectively.

During this time the distillery may have been producing whisky for medicinal purposes but it was certainly storing liquor in their warehouses. This was evidenced by an incident that occurred in February, 1923 that was covered in newspapers across the country. A condensed version of the story was printed in the February 8, 1923 edition of the New York Daily News:

Discovery that bootleggers have got at least 100 barrels of whisky by tunneling from an unoccupied house to the Stewart Distillery was made today when a bootlegger had bared the plot to authorities. The tunnel is 150 feet long and large enough for a man to crawl through. Barrels in the distillery warehouse were tapped and the liquor pumped through a one and a half inch hose to containers in the unoccupied house.

The Baltimore Sun covered the story in much greater detail and actually provided a sketch associated with the theft:

According to a story in the April 18, 1924 edition of the Reading (Pa.) Times this wasn’t the only whisky vanishing from the Baltimore distillery:

Indictments charging two distillery officials with illegal sale of liquor were returned by a special federal grand jury here today.The men indicted were Jacob Katz, vice president and manager of the local warehouse of the Stewart Distillery, Baltimore, and Morris G. Waxler, local manager of the Sherwood Distillery. The indictment against Katz contains thirteen counts alleging illegal sale of 3,000 cases of whisky and twenty-five barrels in September 1922 and with maintaining a nuisance where the whisky was stored…

Ultimately the end of the distillery came in the mid-1920’s. A story in the August 5, 1925 edition of the Baltimore Sun, stated the distillery property changed hands again: Title to the old Stewart Distillery property on Bank Street between Fifth and Seventh Streets was conveyed by the Stewart Distilling Company to W. Guy Crowther, Jacob Ott and Herbert A. Megrow, through the Title Guarantee and Trust Company. The consideration was $75,000.

A month later, this advertisement in the September 6, 1925 edition of the Baltimore Sun announced that the distillery was being dismantled and that much of its contents and equipment was for sale. Finally a June 15, 1927 Baltimore Sun article stated that the distillery property had been sold sold to the Crown Oil and Wax Company:

The former Stewart Distillery property on Bank Street, including eighteen two-story leasehold brick dwellings at 3804 – 3838 Bank Street and machinery, equipment, lumber, etc., was acquired at public auction yesterday by the Crown Oil and Wax Company. The consideration was $25,000 subject to mortgages totaling $54,566.22. Purchase was from Henry Goldstone, trustee, through Sam W. Pattison & Co., auctioneers. No plans for the property have been made by the purchasing Company, it is said.

The last listing I can find for the Stewart Distilling Company was in the 1926 Baltimore City Directory. As far as I can tell, their corporate charter was ultimately forfeited for failure to pay franchise taxes in 1925 and 1926.

Toward the end of Prohibition several different organizations were planning to revive some of the well-known Carstairs trade names. One, actually calling themselves the “Stewart Distilling Company,” was chartered June 14, 1933, and another calling themselves the “American-Stewart Distilling Company,” was a revival of the previously forfeited Stewart corporate charter. D.H. and J.L. Carstairs brought suit to restrain them and two other companies, the “Carstairs Rye Distilleries, Inc.,” and the “Maryland Stewart Distillery Company” from using the Carstairs trade name.

An article in the March 15, 1934 edition of the (Allentown Pa.) Morning Call announced that the U. S. District Court of Maryland had ruled in favor of Carstairs in the case against Carstairs Rye Distilleries. I have to assume that they ultimately came down with similar rulings against the other companies as well because all three were included on a list of delinquent corporations that had forfeited their charters that was printed in the February 11, 1937 edition of Baltimore Sun.

The Morning Call article summarized the situation like this: Carstairs rye whiskey, a favorite with drinkers since colonial times, is off the market unless the famous Philadelphia family bearing the name decides to re-enter the liquor business.

Based on this advertisement for Carstairs Rye, “Back In Baltimore Again,” that appeared in the September 6, 1934 edition of the Baltimore Sun the family did re-enter the liquor business as Carstairs Bros. Distilling Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There’s no mention of Stewart.

The bottle I found (that opens this post) is machine made with what looks like a double ring lip. It’s embossed with this rather awkward phrase in small letters around the shoulder: “LICENSED ONLY FOR USE ON PATENTED VALVE MECHANISM HERE OF BOTTLES WHEN FILLED BY US. RE-USE PROHIBITED. STEWART DISTILLING CO. ONE FIFTH GAL.”

The bottle is consistent with the non-refillable bottle that the company introduced in 1914 calling it “The Supreme Achievement of Standardized Quality, insuring delivery of contents unchanged to the purchaser.” This most likely dates the bottle no earlier than 1914 and and no later than 1919 and the start of Prohibition.

Note: Mike Cavanaugh’s use of newspaper and other resources has done a marvelous job of tracing the history of this distillery, its ownership and brands. It is just one of some 300 posts he has written for baybottles.com and I recommend his blog to all those interested in whiskey bottles, other artifacts, and history.

The American comedian W. C. Fields, shown here, has been a favorite of mine since grade school. From movies like “My Little Chickadee,” and “The Bank Dick.” to his radio sparring with Charlie McCarthy, Fields’ wit and ability to create a distinctive persona have never failed to engage my attention – and that of millions of others. Much of his humor revolved around whiskey, a personal obsession of Fields that ultimately would lead to his death. In life, however, he made it a prime source of his humor. Some examples:

The American comedian W. C. Fields, shown here, has been a favorite of mine since grade school. From movies like “My Little Chickadee,” and “The Bank Dick.” to his radio sparring with Charlie McCarthy, Fields’ wit and ability to create a distinctive persona have never failed to engage my attention – and that of millions of others. Much of his humor revolved around whiskey, a personal obsession of Fields that ultimately would lead to his death. In life, however, he made it a prime source of his humor. Some examples: