From their base in Lexington, members of the Stoll family at various times owned part or all of five Kentucky distilleries, bought and sold such plants frequently, and played cozy with the Whiskey Trust. Their gambits in the liquor trade did not bring them lasting fame but in their own time earned them grudging respect as canny businessmen.

The Stoll family was established in the United States as early as 1818 when Gallus Stoll, a native of Wurtemburg, Germany, brought his family here. After a brief flirtation with Pennsylvania, Gallus headed west, settling in Lexington. There his son, George, was educated, found a wife in a Kentucky native, Mary Scrugham, began a family, and sold furniture and later insurance.

From that union emerged a band of brothers whose names would be among the most noted in distilling circles of the time. The eldest, born in 1851, was Richard Pindall Stoll, shown right, whose jutting chin and stern demeanor give some hint of his determination to succeed. Educated in public schools and at the University of Kentucky, he first learned the liquor business as a federal revenue agent, collecting taxes on distilled products. In time his brother, James Scrugham Stoll, born in 1855, would join him in the whiskey trade.

From that union emerged a band of brothers whose names would be among the most noted in distilling circles of the time. The eldest, born in 1851, was Richard Pindall Stoll, shown right, whose jutting chin and stern demeanor give some hint of his determination to succeed. Educated in public schools and at the University of Kentucky, he first learned the liquor business as a federal revenue agent, collecting taxes on distilled products. In time his brother, James Scrugham Stoll, born in 1855, would join him in the whiskey trade.

In 1880 the brothers, operating as Stoll & Co., established their first distillery, one they called “Commonwealth.” Known in Federal parlance as Registered Distillery #12 in Kentucky’s 7th District, the whiskey-making was accomplished within the brick shell of a old cotton warehouse. This distillery was capable of producing 45 barrels a day or 5,000 barrels per year, made possible by twelve 9,000 gallon fermentation vats in the cellar. Three small warehouses could accommodate 13,000 barrels of aging stock.

After five years Stoll & Co., in a likely shrewd business move, dissolved and its assets were auctioned publicly. A third brother, George J. Stoll, bought the distillery and Richard Stoll acquired several hundred gallons of the stored and aging whiskey. Out of this transaction the Commonwealth Distillery Co. was born, incorporated in 1883. Richard became president and his board included James and a fourth brother, Charles H. Stoll. Members of a Cincinnati liquor wholesaling family, the Pritzes, also came on board. [See my post on Pritz, October 2011.]

Meanwhile a second firm was formed by Richard Stoll with a partner, Robert B. Hamilton, to merchandise the products from the Commonwealth plant. To a great extent using large ceramic jugs for their wholesale customers, they sold under their own names and “Old Elk.” Their symbol for the latter was a large elk head peering from a horseshoe and bearing the motto, “Always Pure.”

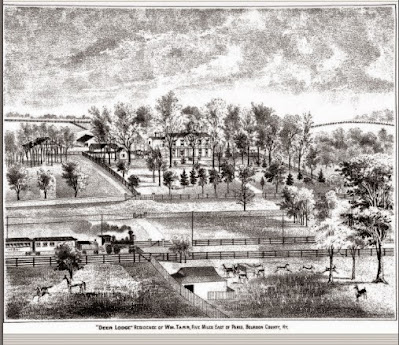

Meanwhile Richard also was becoming involved with William Tarr in the Ashland Distillery (RD #1, 7th District), the facility shown below, located in Fayette County. In a series of business moves this distillery had come into the possession of Tarr, a prominent Kentucky land speculator [See my post on Tarr, February 2015.] In time James Stoll, shown right, also became a major partner. The Ashland distillery issued $50,000 in bonds secured by company assets. The aftereffects of a financial panic and depression in the whiskey industry, as well as some bad personal loans by Tarr, however, soon caused the company to go into bankruptcy.

In May 1897 all Ashland Distillery assets were assigned to James and Richard Stoll, as receivers. The major asset was 10,000 bottles of “Old Tarr" whiskey in bond. Two years later the distillery was sold at auction for $61,000 to a “straw bidder” for the Kentucky Distillery & Warehouse Company, better known as the “Whiskey Trust.” The cartel was now a major force in Kentucky distilling and Charles H. Stoll was its attorney who engineered the deal.

In May 1897 all Ashland Distillery assets were assigned to James and Richard Stoll, as receivers. The major asset was 10,000 bottles of “Old Tarr" whiskey in bond. Two years later the distillery was sold at auction for $61,000 to a “straw bidder” for the Kentucky Distillery & Warehouse Company, better known as the “Whiskey Trust.” The cartel was now a major force in Kentucky distilling and Charles H. Stoll was its attorney who engineered the deal. Meanwhile the brothers continued to be busy on other fronts. In 1891 James Stoll, shown here, teamed with Sanford K. Vannatta, a whiskey broker from Bloomington, Illinois, in a effort to make “Old Elk” a recognized brand across America. As the Stolls' relationship with the Trust ripened they deeded the Commonwealth Distillery to the Trust and it promptly expanded production. James Stoll eventually severed the relationship with Vannatta but continued to wholesale Commonwealth whiskey under the name “Stoll & Company.” James’ son, George J. Stoll III, was made a vice president of this entity.

Meanwhile the brothers continued to be busy on other fronts. In 1891 James Stoll, shown here, teamed with Sanford K. Vannatta, a whiskey broker from Bloomington, Illinois, in a effort to make “Old Elk” a recognized brand across America. As the Stolls' relationship with the Trust ripened they deeded the Commonwealth Distillery to the Trust and it promptly expanded production. James Stoll eventually severed the relationship with Vannatta but continued to wholesale Commonwealth whiskey under the name “Stoll & Company.” James’ son, George J. Stoll III, was made a vice president of this entity.

Returning the several favors the Stolls had bestowed on it, the Trust reciprocated in 1902 by ceding the family the Bond & Lilliard Distillery (RD #274, 8th District), located in Anderson County, on Bailey’ Run near the town of Lawrenceburg Courthouse. In March 1905, once more with Trust assistance, the Stolls acquired the Belle of Nelson (RD #271, 5th District) and the E. L. Miles (RD #146, 5th District) distilleries both located in New Hope. With these acquisitions the Stolls now were running the largest whiskey-making operation in Kentucky.

Returning the several favors the Stolls had bestowed on it, the Trust reciprocated in 1902 by ceding the family the Bond & Lilliard Distillery (RD #274, 8th District), located in Anderson County, on Bailey’ Run near the town of Lawrenceburg Courthouse. In March 1905, once more with Trust assistance, the Stolls acquired the Belle of Nelson (RD #271, 5th District) and the E. L. Miles (RD #146, 5th District) distilleries both located in New Hope. With these acquisitions the Stolls now were running the largest whiskey-making operation in Kentucky.

In addition to Old Elk the Stolls controlled a number of whiskey brands including “Bond & Lilliard,” “Old Buckhorn Rye,” “The Acme,” and “Belle of Nelson.” For the last label the Stolls issued a series of saloon signs that depicted Western card-playing scenes. My favorite is one in which a cowboy is reaching for his gun against a gambler while a Union soldier sits nearby in a drunken stupor.

In March 1903 as the Stolls were at the apogee of their power in Kentucky distilling, Richard died at his residence, only 52 years old. Several months earlier a local newspaper had commented on his vigor and youthful appearance. The cause of death given was a sudden heart attack. He was buried in the Lexington Cemetery. Through his lifetime Richard Stoll had been prominent not only in business but in the civic and political affairs of his community and state. He was elected to represent Fayette County in the Kentucky legislature twice and had run unsuccessfully on the Republican ticket for state treasurer and the U.S. Congress.

In 1907 the Stoll liquor empire underwent a further change as distillery operations were merged with the whiskey marketing arm. This new unified corporation featured James S. Stoll as the president and George J. Stoll III and Richard’s son, John G. Stoll, as vice presidents. Suggesting the Stolls continued relationship with the Whiskey Trust, the cartel’s man, Samuel Stofer, was secretary and treasurer. That arrangement was in place only one year when James Stoll died in May, 1908, during a visit to Oxford, Ohio. He was 53 years old. He too was buried in Lexington Cemetery where the gravestones of the brothers lie not far apart.

With James’ death the liquor empire rapidly came to an end. The days of Stoll wheeling and dealing in Kentucky whiskey were over. Family distilling interests were ceded in their entirety to the Trust, that already had controlled much of the Stolls’ output. At that point the Ashland Distillery, one that had helped launch the family into state prominence, was razed. The family, however, continued to be involved importantly in Lexington. Richard P.’s son, Richard C. Stoll, became an attorney and was a leader in local business, including guiding family ownership of the city’s transit system. He also was a power in Republican party circles.

_2-1.jpg-%2Bc.jpg)