One of the first children to be born of Jewish parents in Oregon, Solomon “Sol” Blumauer rose to prominence in Portland as a whiskey dealer, businessman, pillar of Judaism, community leader and automotive pioneer, only to suffer a tragic and somewhat mysterious death at the age of 66. He is shown here at the wheel of the second automobile ever to be driven in Portland.

One of the first children to be born of Jewish parents in Oregon, Solomon “Sol” Blumauer rose to prominence in Portland as a whiskey dealer, businessman, pillar of Judaism, community leader and automotive pioneer, only to suffer a tragic and somewhat mysterious death at the age of 66. He is shown here at the wheel of the second automobile ever to be driven in Portland.Blumauer was the son of a Bavarian immigrant to the U.S. who initially lived on the East Coast but caught the “gold rush” bug of the 1850s and hurried westward to Oregon with a brother and friends. Before long Sol's father gave up the search for gold and went into business. He returned East long enough to marry Sol’s mother and return to Portland in 1856, where their first son, Louis, has been accounted the first Jewish child born in the state. Sol came along six years later in 1862, born at the family home at Fourth & Morrison Streets.

After attending local grammar and high schools, he went to work at age 18 with a firm called Herter, May & Company that sold stoves and other merchandise. A biography of Blumauer says of this period in his life: “His ability and devotion to their interests won him a partnership in the business and for ten years he traveled for the firm, making all of the towns in Idaho, Oregon and Washington. He was one of the best known salesmen in the northwest and also one of the most successful, establishing a large clientele for the house in

his territory.”

his territory.”Sol also found time for romance and marriage. In 1890 he wed Harriet (Hattie) Fleishner, born in Oregon, whose parents were immigrants from Bohemia, Austria. The Fleishners had settled in Portland and like the Blumauers were engaged in commerce. Sol and Hattie would have but one child, Hazel, born in 1891. That same year, Blumauer disposed of his interest in Herter, May and became one of the stockholders in the Blumauer-Frank Drug Company. That firm, shown here, had been founded by his father and his two older brothers already were employed there.

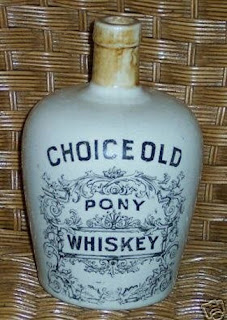

Meanwhile in 1890, two Portland natives had begun a whiskey dealership at 73-75 Washington Street. They were Daniel Kunkel and Eugene Hoch. Eventually Hoch bought out his partner and ran the business by himself for several years. In 1899 Blumauer bought into the whiskey trade, becoming a partner in a company subsequently called Blumauer & Hoch, destined to become the largest wholesale liquor house in Oregon. Its signs, like the one shown here in downtown Portland, could be found throughout the region.

With Blumauer leading the way, the firm featured a range of brand names, including "Curry's Malt", "Dodson's", "Exploration", "Kentucky Club", "O. P. S.", "Old Kentucky Home", "Old Kentucky Home Club", "Old Pony", and "Three Star." It packaged its

whiskey in embossed bottles as well as attractive ceramic jugs. The firm was also well known for its giveaway shot glasses, especially for its flagship brand, Old Kentucky Home.

whiskey in embossed bottles as well as attractive ceramic jugs. The firm was also well known for its giveaway shot glasses, especially for its flagship brand, Old Kentucky Home.While he was establishing himself as a leading businessman, Blumauer was becoming recognized as a community leader, one of the founders of the Native Sons of Oregon and elected its president in 1900. One author has seen the inclusion of Sol and Hattie as native son and daughter as an indication of Jewish acceptance. The Native Sons organization and its publications were notorious for their intolerance

of Native Americans, blacks, and other minority groups.

of Native Americans, blacks, and other minority groups. The Blumauers not only were accepted but leaders. A local newspaper article of 1900 reported Sol’s speech as “Grand President of the Grand Cabin” of Native Sons calling for a concentrated effort to build a monument to Oregon’s pioneers. Sol formed the first Automobile Club in Portland and was a strong advocate for road improvement. He also was an active member of the Tualatin Country Club, the Rotary Club and the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks.

Blumauer’s acceptance into Portland society did not alter his commitment to his Jewish heritage. He was a member of a local synagogue that he and his family helped to found. It was called Congregation Beth Israel. He also served as secretary of the First Hebrew Benevolent Association.

Despite being accepted as a Native Son, Sol Blumauer was about to experience disappointment from his fellow Oregonians. As early as 1844 the Oregon territories voted to prohibit alcoholic beverages. That ban was rescinded just a year later but was reinstated in 1915, four years before National Prohibition. Blumauer & Hoch’s reaction was swift. They moved their liquor operations to San Francisco, sending their wares back into Oregon and elsewhere by mail. After 1917 that avenue was closed off by Federal legislation called the Webb-Kenyon Act. The Blumauer-Hoch San Francisco operation ceased.

In the meantime, the partners had made preparations to switch their operations in Oregon to soft drinks. They were successful in convincing the Anheuser-Busch Company into giving them a franchise. When alcoholic beverages were prohibited in the armed forces in 1916 Anheuser-Busch developed a nonalcoholic malt beverage called Bevo. The timing also was right for Oregon and Blumauer & Hoch found Bevo a good seller during the 1920s. Sol continued to be active in the firm. Even as he got older he continued to be at the head of the company, directing its activities with what contemporaries termed “decisiveness, initiative and keen sagacity.”

in convincing the Anheuser-Busch Company into giving them a franchise. When alcoholic beverages were prohibited in the armed forces in 1916 Anheuser-Busch developed a nonalcoholic malt beverage called Bevo. The timing also was right for Oregon and Blumauer & Hoch found Bevo a good seller during the 1920s. Sol continued to be active in the firm. Even as he got older he continued to be at the head of the company, directing its activities with what contemporaries termed “decisiveness, initiative and keen sagacity.”

Then occurred a tragic and mysterious fall of February 23, 1928. This was how it was described in one Portland obituary: “At about eleven o'clock he had gone up to the second floor of the firm's warehouse and office building at Nos. 428-430 Flanders street, and his disappearance was not noted until the arrival of a man shortly before one o'clock to keep an appointment with him. Search was then begun and carried forward on all three floors before suggestion was made that he might have fainted and slipped into the shaft. Falling forward, Mr. Blumauer is believed to have slipped through the narrow opening and plunged to the bottom of the shaft.”

might have fainted and slipped into the shaft. Falling forward, Mr. Blumauer is believed to have slipped through the narrow opening and plunged to the bottom of the shaft.”

Thus ended the extraordinary career of Sol Blumauer at the age of 66. How and why he might have fallen into the elevator shaft was never thoroughly explored. It was accepted as an accident and nothing more. He was buried in the family plot in Portland’s Beth Israel Cemetery, shown here, as his wife and daughter stood grieving at his graveside. His passing also was mourned by many in the Portland community who had known him as a benefactor and leader. Regrettably, Sol never lived to see the end of National Prohibition which might have launched him once again into the whiskey trade at which he had been so successful.

Blumauer’s acceptance into Portland society did not alter his commitment to his Jewish heritage. He was a member of a local synagogue that he and his family helped to found. It was called Congregation Beth Israel. He also served as secretary of the First Hebrew Benevolent Association.

In the meantime, the partners had made preparations to switch their operations in Oregon to soft drinks. They were successful

in convincing the Anheuser-Busch Company into giving them a franchise. When alcoholic beverages were prohibited in the armed forces in 1916 Anheuser-Busch developed a nonalcoholic malt beverage called Bevo. The timing also was right for Oregon and Blumauer & Hoch found Bevo a good seller during the 1920s. Sol continued to be active in the firm. Even as he got older he continued to be at the head of the company, directing its activities with what contemporaries termed “decisiveness, initiative and keen sagacity.”

in convincing the Anheuser-Busch Company into giving them a franchise. When alcoholic beverages were prohibited in the armed forces in 1916 Anheuser-Busch developed a nonalcoholic malt beverage called Bevo. The timing also was right for Oregon and Blumauer & Hoch found Bevo a good seller during the 1920s. Sol continued to be active in the firm. Even as he got older he continued to be at the head of the company, directing its activities with what contemporaries termed “decisiveness, initiative and keen sagacity.” Then occurred a tragic and mysterious fall of February 23, 1928. This was how it was described in one Portland obituary: “At about eleven o'clock he had gone up to the second floor of the firm's warehouse and office building at Nos. 428-430 Flanders street, and his disappearance was not noted until the arrival of a man shortly before one o'clock to keep an appointment with him. Search was then begun and carried forward on all three floors before suggestion was made that he

might have fainted and slipped into the shaft. Falling forward, Mr. Blumauer is believed to have slipped through the narrow opening and plunged to the bottom of the shaft.”

might have fainted and slipped into the shaft. Falling forward, Mr. Blumauer is believed to have slipped through the narrow opening and plunged to the bottom of the shaft.”Thus ended the extraordinary career of Sol Blumauer at the age of 66. How and why he might have fallen into the elevator shaft was never thoroughly explored. It was accepted as an accident and nothing more. He was buried in the family plot in Portland’s Beth Israel Cemetery, shown here, as his wife and daughter stood grieving at his graveside. His passing also was mourned by many in the Portland community who had known him as a benefactor and leader. Regrettably, Sol never lived to see the end of National Prohibition which might have launched him once again into the whiskey trade at which he had been so successful.

No comments:

Post a Comment