Foreword: As towns, counties and states increasingly banned the consumption of alcohol within their boundaries, many whiskey men were faced with the reality that their customer base increasingly was being eroded — or in some cases eliminated entirely. Some in the liquor trade simply shut their doors, found other things to do or retired. Others seem to have stayed up nights thinking of how they might evade the restrictions of prohibition and continue to make or peddle booze. The results of these gambits differed sharply. This post is devoted to three of them.

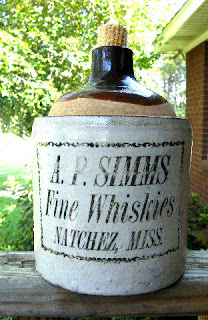

A.P. Simms once was a big man in Natchez, Mississippi. He owned a furniture store. He owned a meat market and a grocery store. He owned a saloon and a flourishing liquor business. That profited him very little when, in 1909 he was, as the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled in unusually strong terms, “perpetually banned from doing business in the state.”

A.P. Simms once was a big man in Natchez, Mississippi. He owned a furniture store. He owned a meat market and a grocery store. He owned a saloon and a flourishing liquor business. That profited him very little when, in 1909 he was, as the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled in unusually strong terms, “perpetually banned from doing business in the state.”

This drastic blow to Simms occurred after the voters of Mississippi with their strong ties to the Baptist Church in 1908 voted a complete ban on the sale of alcohol throughout the state. Natchez, despite its reputation as a rip-roaring river town, was left high and very dry. A. P. Simms was undaunted. Forced to shut down his saloon and liquor retail operation, he simply moved his business across the river to “wet” Louisiana and set up shop. A Simms jug dated 1909, shown below, helps tells the story. Not only did Simms plan to sell whiskey in Louisiana, but also to send it into an increasingly thirsty Mississippi.

Several state courts had ruled that the Interstate Commerce clause of the Constitution made mail order sales into “dry” areas legal until such time as the U.S. Congress decreed otherwise. That did not stop local officials from harrassing parcel companies and railway express by arrests and other legal actions. As a result, some carriers were refusing to carry booze into dry areas.

Simms, always the entrepreneur, sought to obviate that problem by establishing his own carrier in 1908. He called it the “Simms Express & Telegraph Company.” His intent was to take telegraphed orders for whiskey and ship it through his Louisiana operation back into Mississippi, delivering it via his own express company. It did not take officials in the State of Mississippi long to determine that this scheme was an attempt to skirt Prohibition laws. In 1909 they enjoined him from selling or delivering liquors in the state.

Simms, always the entrepreneur, sought to obviate that problem by establishing his own carrier in 1908. He called it the “Simms Express & Telegraph Company.” His intent was to take telegraphed orders for whiskey and ship it through his Louisiana operation back into Mississippi, delivering it via his own express company. It did not take officials in the State of Mississippi long to determine that this scheme was an attempt to skirt Prohibition laws. In 1909 they enjoined him from selling or delivering liquors in the state.

Simms, not one to buckle to the authorities, took the case to the Mississippi Supreme Court asking that the injunction be dissolved. The court not only disagreed, it made the injunction permanent. Moreover, Simms was enjoined “perpetually” from doing business in Mississippi, his company was declared “ousted from the State” and he was required to pay hundreds of dollars in attorney fees, expert witnesses and all court costs. He permanently moved to Louisiana.

Try to put yourself in Herman Egger’s shoes. In an overcrowded field of liquor dealers in Louisville, Kentucky, he was trying to distinguish himself and his “Old Drennon” whiskey by emphasizing mail order sales. As more and more Kentucky counties under “local option” laws voted dry, however, he found his business rapidly dwindling. What could he do?

Try to put yourself in Herman Egger’s shoes. In an overcrowded field of liquor dealers in Louisville, Kentucky, he was trying to distinguish himself and his “Old Drennon” whiskey by emphasizing mail order sales. As more and more Kentucky counties under “local option” laws voted dry, however, he found his business rapidly dwindling. What could he do? Faced with a dismal financial future, Eggers in 1912 from his Jefferson Street liquor house hatched a scheme to sell his whiskey to customers in officially dry Kentucky counties. He composed and sent a form letter to doctors and druggists there asking for help. In his letter the Louisville liquor dealer pointed out that for “medicinal purposes” Kentucky law allowed licensed doctors and druggists to receive whiskey shipments in five gallons or less. Eggers explained: “There are a number of people in your neighborhood who would like to receive goods but cannot order within the state as the laws prevent shipments….If you will permit those who order to have goods shipped to you, without expense to you, it will be an accommodation to both of us.”

Faced with a dismal financial future, Eggers in 1912 from his Jefferson Street liquor house hatched a scheme to sell his whiskey to customers in officially dry Kentucky counties. He composed and sent a form letter to doctors and druggists there asking for help. In his letter the Louisville liquor dealer pointed out that for “medicinal purposes” Kentucky law allowed licensed doctors and druggists to receive whiskey shipments in five gallons or less. Eggers explained: “There are a number of people in your neighborhood who would like to receive goods but cannot order within the state as the laws prevent shipments….If you will permit those who order to have goods shipped to you, without expense to you, it will be an accommodation to both of us.”

Eggers gave the dubious assurance to potential collaborators that his proposal was within Kentucky law and urged them to write him with the names of friends who might be interested in shipments. As a reward for their trouble in handling his liquor, cooperating doctors and druggists would be given one free gallon of whiskey for every ten gallons he shipped. “I do not know if this would be legal,” Eggers acknowledged, but went on to give detailed instructions how the process would work.

Among the physicians who received Eggers’ letter was Dr. Thomas C. Holloway, an eminent gynecologist of Lexington, Kentucky, a town that intermittently had gone dry. Dr. Holloway was caustic in his response to Eggers: “As I have no intention of engaging in the whiskey business, I do not see what right you had to presume I would be interested in your bootlegging proposition.” His letter went on to blister the whiskey man. Then the outraged physician went further by sending the exchange of letters to the Kentucky Medical Journal, the state’s leading publication for doctors and druggists. They published it under the headline “Forum” on September 1, 1912.

Among the physicians who received Eggers’ letter was Dr. Thomas C. Holloway, an eminent gynecologist of Lexington, Kentucky, a town that intermittently had gone dry. Dr. Holloway was caustic in his response to Eggers: “As I have no intention of engaging in the whiskey business, I do not see what right you had to presume I would be interested in your bootlegging proposition.” His letter went on to blister the whiskey man. Then the outraged physician went further by sending the exchange of letters to the Kentucky Medical Journal, the state’s leading publication for doctors and druggists. They published it under the headline “Forum” on September 1, 1912.

With Eggers’ scheme exposed to the world, its utility was gone. Even if tempted initially, doctors and druggists almost certainly walked away from the whiskey dealer’s proposition once it was widely known to the Kentucky medical fraternity and likely revealed to law enforcement officials. Moreover, in addition to having his scheme fail, Eggers had been exposed as someone willing to conspire to evade the law.

Issac Oppenheim was typical of the whiskey men who embraced the “Jug Train,” a scheme legal until after 1913 to bring liquor from “wet” states into “dry” via the railroads, protected from being seized under the Interstate Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Oppenheim, a successful saloonkeeper and liquor dealer was forced out of Atlanta, Georgia, by prohibition into Tennessee, parlayed the Jug Train into personal prosperity.

When Georgia voted its statewide on alcohol production and sales, Oppenheim quickly moved his operation to Chattanooga, Tennessee, 120 miles east of Atlanta. He set up his liquor house at 1013 Chestnut Street and in that railroad town quickly made use of the Jug Train. He ran ads for his “Farm Belle” rye and corn whiskeys in Atlanta newspapers stating: “Fifteen years in Atlanta — send your orders now to Chattanooga.”

A buyer would send Oppenheim money by mail order. Upon receipt of the funds in Chattanooga he would send a “wet” package via the Jug Train to Atlanta. Since it had been purchased out of state, the liquor was legal in Georgia. Competition came from what was known as the “lightning express.” This was an illegal extension of the Jug Train phenomenon. An Atlanta buyer paid cash to an intermediary and thirty minutes later liquor was delivered in a package stamped “Chattanooga” — clearly having made the 120 mile trip in “lightning” time.

A buyer would send Oppenheim money by mail order. Upon receipt of the funds in Chattanooga he would send a “wet” package via the Jug Train to Atlanta. Since it had been purchased out of state, the liquor was legal in Georgia. Competition came from what was known as the “lightning express.” This was an illegal extension of the Jug Train phenomenon. An Atlanta buyer paid cash to an intermediary and thirty minutes later liquor was delivered in a package stamped “Chattanooga” — clearly having made the 120 mile trip in “lightning” time. The transplanted Georgian was not alone in Chattanooga using the Jug Train. A local business directory from 1908 listed some 28 wholesale liquor dealers in “Train Town,” many of them employing railroad express sales to Southern states and localities that had banned alcohol. Shown here is a cartoon that depicts whiskey being pumped south into “dry” Georgia from Chattanooga and north from Jacksonville, Florida, via the rails. Although Atlanta was a principal destination, secondary Jug Trains fanned out from that city across Georgia to smaller towns.

The transplanted Georgian was not alone in Chattanooga using the Jug Train. A local business directory from 1908 listed some 28 wholesale liquor dealers in “Train Town,” many of them employing railroad express sales to Southern states and localities that had banned alcohol. Shown here is a cartoon that depicts whiskey being pumped south into “dry” Georgia from Chattanooga and north from Jacksonville, Florida, via the rails. Although Atlanta was a principal destination, secondary Jug Trains fanned out from that city across Georgia to smaller towns.

The prominence of Jug Trains throughout the United States caused Congress to outlaw the practice in the Webb-Kenyon Act of 1913. Court challenges, however, delayed its enforcement for months. After seven years of riding the Jug Train Oppenheim was forced to shut the doors on his Chattanooga liquor house in 1915 when Tennessee also went “dry.” He returned to Atlanta a considerably wealthier man to run a cigar business. From Chattanooga virtually every day he had shipped liquor back to Georgia via the Jug Train. No only did railroad traffic make him rich, it provided a measure of sweet revenge on the state that had banned the sale of alcohol and put him out business in Atlanta.

Addendum: This is to alert both followers of this blog and others that I have a new website involving whiskey. It is a compilation of more than thirty vignettes about Old West saloons and saloonkeepers. Outlaws, gunslingers, and shootings abound. This new blog can be accessed at wet enterprise: select saloons of the old west@blogspot.com. If this new site proves popular, other compilations under the “wet enterprise” heading may be forthcoming.