Dubuque and East Dubuque are municipalities with similar names yet in two different states and divided by the Mississippi River. Yet John Peter Ellwanger and his liquor business were destined by fate to play an important role in both cities.

Ellwanger was born in 1849, in Hesse Darmstadt, Germany. He was the fourth in the line of eight children produced by his mother, Agatha Jaeger, and father, Peter Edward Ellwanger. Despite Peter being a pianist and music teacher of some repute in his native land, the Ellwangers determined to emigrate. The family boarded the ship, Venice, in Le Havre, France, in 1852 and sailed to New Orleans. John Ellwanger was only three years old.

Upon arrival on American soil, the family quickly traveled to, and settled in, Dubuque, Iowa. Members of Agatha’s family, the Jaegers, had preceded them to the city, one which had attracted many German immigrants. They gave the Ellwangers a warm welcome. Peter found work as piano teacher and piano tuner to support his growing family.

Early on John Peter showed great promise, graduating from the Bayless Business College in Dubuque at the age of 13 and immediately going to work. His first venture in the business world was as a “bundle boy” in the dry goods establishment of Wood, Luke & company until they sold out to Sheffield, Wood, & Company, who changed the business to a strictly wholesale establishment. Ellwanger then entered the employ of merchant James Levi and remained with him about a year, leaving to become a clerk in a clothing business.

In 1871 at the age of 22, having served a nine year apprenticeship in several mercantile establishments, Ellwanger went to work for his older cousin, Francis Jaeger, already a successful Dubuque businessman. Jaeger had had begun as a co-partner in a wholesale grocery business, eventually bought out his partner, and shifted the company focus to a wholesale liquor dealership. Joining Jaeger as a bookkeeper, Ellwanger proved to be a “quick learner” of the whiskey trade.

Steady employment with Jaeger apparently emboldened Ellwanger to court and marry Sophia Buckman, the daughter of the former sheriff of Dubuque, William D. Buckman, who was a well known figure in the community. The couple would birth three children, William E., Ralph and Josephine. By June 1875, Ellwanger had saved enough money so that with a partner, Michael Brady, he purchased a controlling interest in Jaeger’s liquor company. It then was renamed Brady, Ellwanger and Company

As Dubuque grew, the business grew with it. In 1887 the first bridge was built across the Mississippi river linking the Iowa town with East Dubuque, Illinois. Replacing the need for ferries, it was popularly called the “High Bridge” because it was constructed high enough to allow steamboats with tall smoke stacks to pass underneath. The bridge opened up new commerce for Dubuque and Brady, Ellwanger, attracting customers from Illinois and close-by Wisconsin -- an area sometimes called the “Tri-States.”

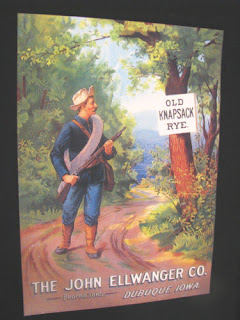

With the death of Michael Brady in 1899, Ellwanger incorporated the business, became its president until his death, and renamed the company after himself. The John Ellwanger Co. then launched on a campaign to become Dubuque’s largest and finest liquor dealer. He featured a series of brands, including "Old Knapsack Rye", "Pap Poose","Saddle Bags," "Real Merit", and "J.E.T." He advertised these through expensive lithographed signs for saloons, as the one shown here for Old Knapsack. He also ordered expensive containers for his whiskey, like the Thuemler Pottery-made canteen for Old Knapsack Rye shown here and an unusual glass bottle for Saddle Bags Rye. The amber bottle appears to approximate a saddle bag. Among his giveaways to saloons and other special customers also were shot glasses, including a twelve-fluted glass with an etched “Pap Poose.”

Ellwanger was also involved in multiple political and business activities. He served as Chairman of the County Democratic Central Committee and was an elector for the Democrats in the 1900 Presidential election where he voted for William Jennings Bryan. He was a director and major stockholder of the Union Electric prior to its purchase by Dubuque Electric Company. He was a director of the Iowa Trust & Savings Bank, the Key City Fire Insurance Co., the Dubuque Alter manufacturing Co. and the Dubuque High Bridge Co., where he also served as secretary.

Soon enough the bridge would play an even more important role in Ellwanger’s life. After years of trying, the forces of Prohibition in Iowa prevailed and in 1916 the state completely banned alcohol. Just across the river, however, Illinois was still wet. Ellwanger wasted no time in moving his operation over the bridge to East Dubuque. A shot glass memorialized that move across the Mississippi.

On the first “Dry” Saturday in 1916, the movement on the High Bridge from Dubuque going east was so intense that vehicles had to be stopped until traffic snarls leading to Illinois could be cleared. The number of East Dubuque liquor licenses soared despite the town government doubling the fee. Little effort apparently was made to apprehend those bringing liquor back into Iowa. Local lore recounts that some of Dubuque’s thirsty bought their liquor in East Dubuque and trundled it across the bridge in baby buggies. Many Iowans, no doubt, bought from The John Ellwanger Co.

Following the death of his wife, Sophia, in 1904, Ellwanger married again in 1906. This time it was to Mrs. S. Fannie Lewis Buckman, possibly his widowed sister-in-law. In 1915, they moved into a large home at 1329 Main Street, Dubuque, that still stands, as shown here. Two years later in April, 1917, Ellwanger died at this residence, surrounded by his family. His obituary in the local Telegraph Herald called him, “one of Dubuque’s leading businessmen and financiers.” Said to have been a devout Catholic, his funeral services were held at St. Mary’s Church and he was buried in a private ceremony in nearby Linwood Cemetery. Friends were requested not to send flowers.

Son William took over running the John Ellwanger Co. His business activities, however, were shortly overtaken by National Prohibition. At the end of 1919, William was forced to shut down the business his father had built. East Dubuque, by this time had something of a reputation as a “sin city.” It did not take well to the ban on alcohol. The night in 1920 that Prohibition became Federal law and padlocks were put on saloons, thousands of people from the Tri-state Area rioted there and attempted to tear down City Hall. When firemen sprayed water to calm the crowd, rowdies cut the hoses and the shower was reduced to a dribble. The main street of East Dubuque is shown here as it looked in 1920.

William Ellwanger, who died in 1944, himself became a prominent Dubuque businessman, serving as both president of the Fitzgerald Cigar Co. and president of the Dubuque Bridge Co. The latter was a fitting position for someone whose customers had used the span for years to abate their thirst. John Peter Ellwanger would have been proud.

Ellwanger was born in 1849, in Hesse Darmstadt, Germany. He was the fourth in the line of eight children produced by his mother, Agatha Jaeger, and father, Peter Edward Ellwanger. Despite Peter being a pianist and music teacher of some repute in his native land, the Ellwangers determined to emigrate. The family boarded the ship, Venice, in Le Havre, France, in 1852 and sailed to New Orleans. John Ellwanger was only three years old.

Upon arrival on American soil, the family quickly traveled to, and settled in, Dubuque, Iowa. Members of Agatha’s family, the Jaegers, had preceded them to the city, one which had attracted many German immigrants. They gave the Ellwangers a warm welcome. Peter found work as piano teacher and piano tuner to support his growing family.

Early on John Peter showed great promise, graduating from the Bayless Business College in Dubuque at the age of 13 and immediately going to work. His first venture in the business world was as a “bundle boy” in the dry goods establishment of Wood, Luke & company until they sold out to Sheffield, Wood, & Company, who changed the business to a strictly wholesale establishment. Ellwanger then entered the employ of merchant James Levi and remained with him about a year, leaving to become a clerk in a clothing business.

In 1871 at the age of 22, having served a nine year apprenticeship in several mercantile establishments, Ellwanger went to work for his older cousin, Francis Jaeger, already a successful Dubuque businessman. Jaeger had had begun as a co-partner in a wholesale grocery business, eventually bought out his partner, and shifted the company focus to a wholesale liquor dealership. Joining Jaeger as a bookkeeper, Ellwanger proved to be a “quick learner” of the whiskey trade.

Steady employment with Jaeger apparently emboldened Ellwanger to court and marry Sophia Buckman, the daughter of the former sheriff of Dubuque, William D. Buckman, who was a well known figure in the community. The couple would birth three children, William E., Ralph and Josephine. By June 1875, Ellwanger had saved enough money so that with a partner, Michael Brady, he purchased a controlling interest in Jaeger’s liquor company. It then was renamed Brady, Ellwanger and Company

As Dubuque grew, the business grew with it. In 1887 the first bridge was built across the Mississippi river linking the Iowa town with East Dubuque, Illinois. Replacing the need for ferries, it was popularly called the “High Bridge” because it was constructed high enough to allow steamboats with tall smoke stacks to pass underneath. The bridge opened up new commerce for Dubuque and Brady, Ellwanger, attracting customers from Illinois and close-by Wisconsin -- an area sometimes called the “Tri-States.”

With the death of Michael Brady in 1899, Ellwanger incorporated the business, became its president until his death, and renamed the company after himself. The John Ellwanger Co. then launched on a campaign to become Dubuque’s largest and finest liquor dealer. He featured a series of brands, including "Old Knapsack Rye", "Pap Poose","Saddle Bags," "Real Merit", and "J.E.T." He advertised these through expensive lithographed signs for saloons, as the one shown here for Old Knapsack. He also ordered expensive containers for his whiskey, like the Thuemler Pottery-made canteen for Old Knapsack Rye shown here and an unusual glass bottle for Saddle Bags Rye. The amber bottle appears to approximate a saddle bag. Among his giveaways to saloons and other special customers also were shot glasses, including a twelve-fluted glass with an etched “Pap Poose.”

Ellwanger was also involved in multiple political and business activities. He served as Chairman of the County Democratic Central Committee and was an elector for the Democrats in the 1900 Presidential election where he voted for William Jennings Bryan. He was a director and major stockholder of the Union Electric prior to its purchase by Dubuque Electric Company. He was a director of the Iowa Trust & Savings Bank, the Key City Fire Insurance Co., the Dubuque Alter manufacturing Co. and the Dubuque High Bridge Co., where he also served as secretary.

Soon enough the bridge would play an even more important role in Ellwanger’s life. After years of trying, the forces of Prohibition in Iowa prevailed and in 1916 the state completely banned alcohol. Just across the river, however, Illinois was still wet. Ellwanger wasted no time in moving his operation over the bridge to East Dubuque. A shot glass memorialized that move across the Mississippi.

On the first “Dry” Saturday in 1916, the movement on the High Bridge from Dubuque going east was so intense that vehicles had to be stopped until traffic snarls leading to Illinois could be cleared. The number of East Dubuque liquor licenses soared despite the town government doubling the fee. Little effort apparently was made to apprehend those bringing liquor back into Iowa. Local lore recounts that some of Dubuque’s thirsty bought their liquor in East Dubuque and trundled it across the bridge in baby buggies. Many Iowans, no doubt, bought from The John Ellwanger Co.

Following the death of his wife, Sophia, in 1904, Ellwanger married again in 1906. This time it was to Mrs. S. Fannie Lewis Buckman, possibly his widowed sister-in-law. In 1915, they moved into a large home at 1329 Main Street, Dubuque, that still stands, as shown here. Two years later in April, 1917, Ellwanger died at this residence, surrounded by his family. His obituary in the local Telegraph Herald called him, “one of Dubuque’s leading businessmen and financiers.” Said to have been a devout Catholic, his funeral services were held at St. Mary’s Church and he was buried in a private ceremony in nearby Linwood Cemetery. Friends were requested not to send flowers.

Son William took over running the John Ellwanger Co. His business activities, however, were shortly overtaken by National Prohibition. At the end of 1919, William was forced to shut down the business his father had built. East Dubuque, by this time had something of a reputation as a “sin city.” It did not take well to the ban on alcohol. The night in 1920 that Prohibition became Federal law and padlocks were put on saloons, thousands of people from the Tri-state Area rioted there and attempted to tear down City Hall. When firemen sprayed water to calm the crowd, rowdies cut the hoses and the shower was reduced to a dribble. The main street of East Dubuque is shown here as it looked in 1920.

William Ellwanger, who died in 1944, himself became a prominent Dubuque businessman, serving as both president of the Fitzgerald Cigar Co. and president of the Dubuque Bridge Co. The latter was a fitting position for someone whose customers had used the span for years to abate their thirst. John Peter Ellwanger would have been proud.