Tarr’s roots were deep in Kentucky. His grandfather, Charles Tarr, was born on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, and migrated about 1790 as a newlywed with his wife to Nicholas County, Kentucky. A farmer, Charles is said to have become one of the prominent men of the region. Although he later decamped for Illinois, one son, John B. Tarr, remained, married Milly Turner, and raised a family of five sons and two daughters. Among the sons was William, born in June 1825. The Tarr family was not wealthy and a biographer noted of William: “He began life as a poor boy….”

The youthful Tarr’s first enterprise was raising and selling watermelons. From there he graduated to mule trading, an activity that gave him sufficient money to farming on rented land with his brother. After a few years working the soil with evident success, the two parted ways. Tarr went into business for himself, making whiskey on a small scale. With the profits from that enterprise in the early 1860s he invested in what became known as the Chicken Cock Distillery in East Paris, Kentucky. He became a partner in 1863 and operated the distillery until 1868 when he sold his share in favor of new opportunities, primarily in land speculation.

During the 1860s, Tarr also was having a personal life. He married a Kentucky- born woman named Sarah Fisher, the daughter of W.W. and Sarah (Garth) Fisher. She was known by her middle name “Findlay,” the only one on her gravestone. The couple would have two sons, Thompson, born in 1866 and Fisher, born in 1870.

The whiskey-making opportunity that presented itself to Tarr was the Ashland Distillery in Lexington, Kentucky. It had been established in 1865 by Turner, Clay & Co., a business that included Horace Turner, Samuel Clay and Thomas Mitchell. The facility was located on Manchester Street (Frankfort Pike) between Cox and Perry and was the first to obtain a Federal Register distillery license (RD #1, 7th District) in Lexington. Its products were marketed as “Ashland Whiskey.” Identified by the logo shown above, the firm produced about 30 barrels of whiskey a day, slightly less than its 37 barrel capacity. The partners also completed a bonded warehouse, one said to be “fireproof.”

The whiskey-making opportunity that presented itself to Tarr was the Ashland Distillery in Lexington, Kentucky. It had been established in 1865 by Turner, Clay & Co., a business that included Horace Turner, Samuel Clay and Thomas Mitchell. The facility was located on Manchester Street (Frankfort Pike) between Cox and Perry and was the first to obtain a Federal Register distillery license (RD #1, 7th District) in Lexington. Its products were marketed as “Ashland Whiskey.” Identified by the logo shown above, the firm produced about 30 barrels of whiskey a day, slightly less than its 37 barrel capacity. The partners also completed a bonded warehouse, one said to be “fireproof.”

The distillery seemed to have struggled financially from the outset and after Turner’s death in 1871, the partnership dissolved. Tarr with Thomas Megibben, a Lexington dry goods merchant, acquired it and restarted production. They continued to produce the Ashland label and introduced a new brand, initially called “Wm. Tarr Whiskey” and later “Old Tarr.” Both brands were produced in bourbon and rye versions. Another Tarr whiskey label was Belle of Marion,

The distillery seemed to have struggled financially from the outset and after Turner’s death in 1871, the partnership dissolved. Tarr with Thomas Megibben, a Lexington dry goods merchant, acquired it and restarted production. They continued to produce the Ashland label and introduced a new brand, initially called “Wm. Tarr Whiskey” and later “Old Tarr.” Both brands were produced in bourbon and rye versions. Another Tarr whiskey label was Belle of Marion,

The decade of the 70s brought two setbacks to Tarr. In 1873, his wife, Sarah, died, still a very young woman, leaving William with two small boys to raise. Perhaps to give his children a mother, three years later he married a second time. His new bride was Mary Fisher, a sister to his first wife and a woman 34 years his junior. They would have three children of their own: James born in 1877; William Orr, 1878; and Mary Best, 1880.

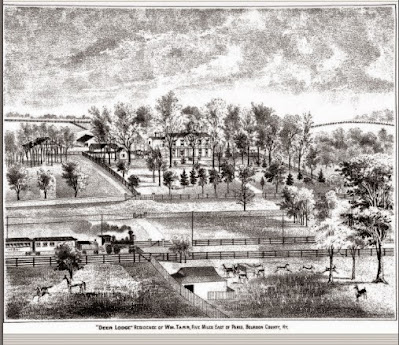

For this growing family he built what was described as “one of the most beautiful homes in Bourbon County, having provided it with all the modern conveniences and tasteful designs, and a large and commodious park well stocked with deer.” Shown here in a contemporary illustration, the Tarr home had originated as a smaller Federal style building but William greatly enlarged it to accommodate extensive Italianate features. The main entry way was made of Flemish-bond brickwork, an expensive and labor intensive addition.

Tarr’s second setback of the 70s was a raging fire in 1879 that destroyed his distillery. Not only was it largely of wooden construction but Lexington did not have a waterworks to provide a supply of water to fight the conflagration. The structures burned quickly and out of control. The disaster apparently triggered a company reorganization. Tarr remained the president, with three partners. He owned 40%, Megibben another 40%, and the remaining 20% split between Sam Clay, a company salesman, and a plant manager who was Megibben’s son-in-law. Under this arrangement the distillery and warehouses were rebuilt at the cost of $75,000 ($1.8 million today), this time in brick with fire proof slate or metal roofs.

Tarr’s distillery, shown above rebuilt, was a “state of the art” facility on eleven acres. The floor space covered 25,000 square feet and included 14 fermentation tubs, each with a capacity of 9,500 gallons. The primary mash tub held 10,000 gallons, with 400 smaller mash tubs of 101 gallons each. In lieu of refrigeration, the small tubs allowed a faster cooling process. By 1882 thirty-five workers were employed to produced about 45 barrels of whiskey daily, mashing 300 bushels of corn and 120 bushels of rye and barley malt. Corn was purchased from local farmers but rye and barley malt came by train from the West on a siding running into the facility. Barrels of whiskey were transported out by rail. Water for the distillery was supplied from a nearby spring, at first under a lease and later purchased outright by Tarr. Pumps supplied 200,000 gallons of fresh limestone water daily through a system of pipes. Annual whiskey production grew to six thousand barrels, valued at $150,000 ($3.1 million today). Some 18,000 barrels were kept in bonded storage. Old Tarr was advertised as "always true."

As the head of this distilling giant, Tarr was lionized for his entrepreneurial genius. One biographer extolled him as “…A man of great business tact and ability, his large and increasing business interests extending throughout the country.” In 1882 another observer opined: “…He has become one of the money kings of the Blue Grass.” Yet even then the seeds of destruction for this “up from the bootstraps” entrepreneur were being sown. William Tarr, ever the speculator, fell in love with railroads. The extent of his fascination can be seen in the illustration of his estate above. The train depicted there was running on a right-of-way the “Money King” had donated in sight of his mansion windows.

As the head of this distilling giant, Tarr was lionized for his entrepreneurial genius. One biographer extolled him as “…A man of great business tact and ability, his large and increasing business interests extending throughout the country.” In 1882 another observer opined: “…He has become one of the money kings of the Blue Grass.” Yet even then the seeds of destruction for this “up from the bootstraps” entrepreneur were being sown. William Tarr, ever the speculator, fell in love with railroads. The extent of his fascination can be seen in the illustration of his estate above. The train depicted there was running on a right-of-way the “Money King” had donated in sight of his mansion windows.

Even before the Civil War a railroad from Lexington southeast through the coalfield of Kentucky and onto Virginia had been proposed. After the war speculation in railroads was rampant and Tarr was not immune. With his distillery partner Megibben he formed the Kentucky Union Railroad Company in 1872 with Kentucky and out of state investors. Shown below is a $1,000 bond certificate issued by the company.

From the beginning the railroad was vexed by problems. The construction relied on convicts for labor. Maltreated, some died and were laid in unmarked graves. Other escaped during winter months, reputedly to seek warmth and proper clothing. The project also required the erection of a 500-foot trestle over a river. Financial problems and a shortage of steel caused delays into 1884. When completed, the railroad cost almost $1 million ($25 million today) and had been funded largely by undercapitalized distillers, with Tarr the lead investor. Unable to gain additional financing, he and his partners in 1886 were forced to sell the railroad at a ruinous 50% loss.

From the beginning the railroad was vexed by problems. The construction relied on convicts for labor. Maltreated, some died and were laid in unmarked graves. Other escaped during winter months, reputedly to seek warmth and proper clothing. The project also required the erection of a 500-foot trestle over a river. Financial problems and a shortage of steel caused delays into 1884. When completed, the railroad cost almost $1 million ($25 million today) and had been funded largely by undercapitalized distillers, with Tarr the lead investor. Unable to gain additional financing, he and his partners in 1886 were forced to sell the railroad at a ruinous 50% loss.

The decline of Tarr’s fortunes seem to have triggered another reorganization of the Ashland Distillery. By 1888 Sam Clay had departed and his share was obtained by Thompson Tarr, William’s eldest son. By 1890 Megibben had died and Tarr purchased his interest and installed Thompson as company vice president. Now the Tarrs owned the Ashland distillery almost in its entirety. Always aggressive, William in 1892 purchased the nearby Lexington Distillery to acquire 10,000 barrels of bourbon in storage. He then demolished the plant and moved the whiskey to his own warehouses.

Although this activity might indicate continued strength of Tarr’s enterprises, he had been weaken financially by the railroad debacle. Furthermore, he had endorsed notes for family and friends who defaulted during the national “Panic of 1893,”, leaving him with judgments ranging from $200 to $8,000. As as way out, Tarr invited into the management members of the Stoll family of Lexington who controlled a number of distilleries in central Kentucky. In January 1897 Tarr issued $50,000 in bonds as a last ditch effort to save his distillery. In May of that year, the end came. He declared bankruptcy and all assets were assigned to the Stolls. Those included 10,000 barrels of Tarr’s bourbon and his distillery. The latter was sold at auction in 1899, purchased by a straw bidder for the Kentucky Distilling & Warehouse Co., widely known as “The Whiskey Trust.”

Although this activity might indicate continued strength of Tarr’s enterprises, he had been weaken financially by the railroad debacle. Furthermore, he had endorsed notes for family and friends who defaulted during the national “Panic of 1893,”, leaving him with judgments ranging from $200 to $8,000. As as way out, Tarr invited into the management members of the Stoll family of Lexington who controlled a number of distilleries in central Kentucky. In January 1897 Tarr issued $50,000 in bonds as a last ditch effort to save his distillery. In May of that year, the end came. He declared bankruptcy and all assets were assigned to the Stolls. Those included 10,000 barrels of Tarr’s bourbon and his distillery. The latter was sold at auction in 1899, purchased by a straw bidder for the Kentucky Distilling & Warehouse Co., widely known as “The Whiskey Trust.”

His reputation as a canny businessman in tatters, in 1898 Tarr retired to his farm with his wife, Mary. He was 73 years old and still owned considerable tracts of land in Bourbon County and Eastern Kentucky. The receivership played out for some 14 years, ending only in 1911 when Tarr’s debts were finally settled. The lengthy process was a continuing reminder to everyone of how far he had fallen. A year later Tarr was dead, 86 years old. He was buried in a Paris, Kentucky, cemetery with a cement headstone, adorned with a rose. It marks his name and dates of birth and death. Both of his wives are buried near him. The notice of his death in a Lexington newspaper identified him pointedly as “formerly one of the most widely known distillers of the United States.”

The William Tarr Distillery and associated brand name were retained for a time by subsequent ownerships but the plant finally was closed down by National Prohibition. One night in March 1920, a masked gang of thieves raided the warehouses at the distillery. Overpowering two guards, they took 96 cases of bonded whiskey valued at $20,000 from the government-controlled facility. To safeguard the remaining whiskey it was removed to one of the U.S. “concentration warehouses.” Today the only vestige of Tarr’s distillery is one warehouse, now serving as a Lexington bar. As shown below, the family mansion now stands abandoned and sadly has been allowed to fall into disrepair.

_2-1.jpg-%2Bc.jpg)

Would you be interested in a unopened pint of mr tarrs whiskey over 110 yrs old

ReplyDeleteDear Scott: Thanks for being in touch. Your pint of Tarr whiskey is very intriguing and I would be interested a picture of the bottle, but do not collect such items. Would also be interested in the taste of the contents. All the experts say it should still be good still. But not having tasted any that old, I am not in a position to say. You might wish to take a sip and let me know. Or sell it as is to those who pay dearly for something like this. Jack

ReplyDeleteMy great grandmother was a Tarr. When I was young, she told me that half the family took off from MD to go west to find their fortune. The family never heard from them again. The remaining MD Tarrs figured they either perished or didn't want to share their newly found fortune due to the fact that they never heard from them again. This article is the missing piece of the Tarr puzzle for me. :) THANK YOU!

ReplyDeleteFoster Mom: I hope you have been able to be connected to an part of the Tarr family. The name is English and not uncommon, however. I had a professor colleague at the University of Wisconsin named Tarr. Checking in at Ancestry.com might be helpful.

ReplyDeleteJack, was your professor colleague David William Tarr, professor at Madison, now retired to Asheville, NC?

DeleteTim: I believe you are right. Dr. David Tarr. I remember, like me, he was a political scientist and we met at several conferences back in the 1960s-1980s. I recall he was a very bright, nice guy. Glad to know he is still with us.

DeleteI am a Tarr, we have traced family records to MA/CT, some family settled in MD where it then split some to KY, others to PA, PA side made fortune in Oil, Tarr Mansion in Meadeville PA is all that remains. We have an Old Tarr Whiskey thimble that was from grandparents family. Thank You for this piece on missing family history and hopefully it will help ofhters

ReplyDeleteMy 7th ggfather was Richard Tarr, the first settler of Rockport, MA (Sandy Bay Colony). Do you have a connection to this family? My only connection thus far to William Tarr is that he is the 2nd cousin of the wife of my 3rd cousin 4x removed - on my mother's side. I was fortunate to have stumbled upon the RD1 / Tarr store recently and was able to purchase a bottle and given 2 hats. Now I am searching for a closer connection to William.

DeleteDoes anyone have an image of William Tarr?

ReplyDeleteUnknown: When I do a vignette on a whiskey man, I also search diligently for an image, photo, drawing, or cartoon, and keep looking later. In Tarr's case have not found anything.

ReplyDeleteI am a Tarr in England -- maybe the origin family? From the Southwest in Somerset. Any family connections?

ReplyDeleteTarr: No idea. Tarr is a fairly common British name.

ReplyDelete