Foreword: How did Americans “have fun” in pre-Prohibition day a century and more ago? More people were living in cities and feeling the stress of an increasingly mechanized environment. Looking for new ways to recreate, many Americans were eager to spend their leisure time in more adventurous forms of entertainment. Better transportation options like the railroad, streetcars and automobiles made it possible to travel distances to recreate. Liquor sales had given whiskey men the money to extend their enterprises to include such opportunities. This is the story of four of them.

Edwin S. Hughes, shown here with a fancy mustache, was New Jersey born but early in life gravitated West. After stints in Leadville and Aspen, Colorado, in 1887 he moved to Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and started his own bottling company. Shown below, Glenwood Springs, originally called “Defiance” by its rambunctious residents, was anything but a tourist hub. Located in a mountain valley at the confluence of the Colorado and Roaring Fork River, many more saloons, gambling houses and brothels existed than grocery stores and restaurants. As one local historian has put it: “More saloons existed here than a city needed, honestly, but we had them.”

Edwin S. Hughes, shown here with a fancy mustache, was New Jersey born but early in life gravitated West. After stints in Leadville and Aspen, Colorado, in 1887 he moved to Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and started his own bottling company. Shown below, Glenwood Springs, originally called “Defiance” by its rambunctious residents, was anything but a tourist hub. Located in a mountain valley at the confluence of the Colorado and Roaring Fork River, many more saloons, gambling houses and brothels existed than grocery stores and restaurants. As one local historian has put it: “More saloons existed here than a city needed, honestly, but we had them.”  As a newcomer, Hughes had the wisdom to see the potential of the area in the extensive geothermal resources that existed, most famously in hot springs, shown here. It was an era when many believed that mineral waters held restorative qualities and could even cure diseases. He saw that a market existed. The arrival of railroads, the Denver and Rio Grande from the east, the Colorado Midland from the south, meant that people could travel to Glenwood Springs in relative comfort. Hughes would provide encouragement.

As a newcomer, Hughes had the wisdom to see the potential of the area in the extensive geothermal resources that existed, most famously in hot springs, shown here. It was an era when many believed that mineral waters held restorative qualities and could even cure diseases. He saw that a market existed. The arrival of railroads, the Denver and Rio Grande from the east, the Colorado Midland from the south, meant that people could travel to Glenwood Springs in relative comfort. Hughes would provide encouragement.

Over time Hughes gained control of the hot springs, garnered the exclusive right to bottle the “medicinal” waters, and was elected to the town board where he became a force for better streets and sidewalks and curbing gambling and prostitution. Opening his own liquor store in 1894, for a time he exercised a monopoly in Glenwood Springs to dictate whiskey and beer supplies, pricing, and even the establishment of new saloons.

After helping to tame this “rowdy” town and make it a tourist destination, Hughes capitalized by buying the Hotel Colorado, patterned after the Villa de Medici in Italy. Hotel Colorado became a favored destination for Easterners lured by the mineral water baths. Arriving mostly by train, they reveled in the comforts it afforded as well as its firework displays, live music and elegant dining. After extended stays there by Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, Hotel Colorado gained the name “Little White House of the West.” With considerable help from Ed Hughes, Glenwood Springs had become a retreat for the rich and famous.

After helping to tame this “rowdy” town and make it a tourist destination, Hughes capitalized by buying the Hotel Colorado, patterned after the Villa de Medici in Italy. Hotel Colorado became a favored destination for Easterners lured by the mineral water baths. Arriving mostly by train, they reveled in the comforts it afforded as well as its firework displays, live music and elegant dining. After extended stays there by Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, Hotel Colorado gained the name “Little White House of the West.” With considerable help from Ed Hughes, Glenwood Springs had become a retreat for the rich and famous. Able to prosper as the proprietor of a liquor house in Salt Lake City, Utah, the heart of Mormon country, Jacob Bergerman seems quickly to have achieved recognition in local business circles as a canny operator. During the early 1900s, he was entrusted with being the proprietor and manager of Calders Park, a well-known Salt Lake City recreational site and resort. He ran a saloon on the premises where both boisterous drinkers and more respectable sorts, as the pair shown in a 1900s John Held New Yorker cartoon, could have their leisure.

Able to prosper as the proprietor of a liquor house in Salt Lake City, Utah, the heart of Mormon country, Jacob Bergerman seems quickly to have achieved recognition in local business circles as a canny operator. During the early 1900s, he was entrusted with being the proprietor and manager of Calders Park, a well-known Salt Lake City recreational site and resort. He ran a saloon on the premises where both boisterous drinkers and more respectable sorts, as the pair shown in a 1900s John Held New Yorker cartoon, could have their leisure.

In 1904, Bergerman was awarded a lease to manage what the press called “an ideal pleasure resort” named “The Lagoon.” Hired by a regional railway company, Jacob was put on notice that his contract was dependent upon enforcing order among patrons and insuring that “all concessions in the shape of restaurants, bars, etc. must be conduct (sic) in first class manner.” It was not until 1817, and statewide prohibition, that Bergerman had to cease all liquor sales at Calders Park and the Lagoon.

As a partner in The Levy and Lewin Mercantile Company, Albert Lewin, who came from Germany with his family as a baby, had made a reputation in Denver as an accomplished liquor dealer but found his interests moving in other directions. In March 1907 he joined a group of investors that incorporated the Lakeside Realty and Amusement Company to create a large amusement park adjacent to Denver. Managed by Lewin, Lakeside also incorporated as a municipality in order to be free of Denver’s restrictive laws on the sale and serving of alcohol. An employee of Levy & Lewin Mercantile was elected mayor.

As a partner in The Levy and Lewin Mercantile Company, Albert Lewin, who came from Germany with his family as a baby, had made a reputation in Denver as an accomplished liquor dealer but found his interests moving in other directions. In March 1907 he joined a group of investors that incorporated the Lakeside Realty and Amusement Company to create a large amusement park adjacent to Denver. Managed by Lewin, Lakeside also incorporated as a municipality in order to be free of Denver’s restrictive laws on the sale and serving of alcohol. An employee of Levy & Lewin Mercantile was elected mayor.

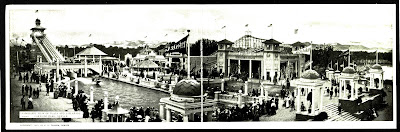

Lewin became a darling of the Denver press. When the 100,000 lights in the park were turned on for a test, the whiskey man was quoted. The Denver Republican also reported that Lewin had successfully tested the motors on all the park rides. When the park opened the same paper declared that the Lakeside management had given the people of Colorado “the greatest and finest amusement park ever attempted West of Chicago.” Shown above, it was, indeed, a spectacular scene.

Two years after his success at Lakeside, Lewin looked for a new challenge. He found it in an earlier amusement park built near Denver called Manhattan Beach. After it burned in 1908, Lewin headed an investment group that rebuilt it, adding a roller coaster, shown here, an over-the-water dance pavilion, and a new theater. Renamed “Luna Park,” venture was not as successful as Lewin’s earlier venture. Lakeside has remained a favorite recreation spot for Coloradans; Luna Park eventually was razed.

Two years after his success at Lakeside, Lewin looked for a new challenge. He found it in an earlier amusement park built near Denver called Manhattan Beach. After it burned in 1908, Lewin headed an investment group that rebuilt it, adding a roller coaster, shown here, an over-the-water dance pavilion, and a new theater. Renamed “Luna Park,” venture was not as successful as Lewin’s earlier venture. Lakeside has remained a favorite recreation spot for Coloradans; Luna Park eventually was razed. While still a teenager, Columbus Ed Carmichael, known as “C. Ed,” moved to Ocala, then just a sleepy Florida town, where he helped his father establish a combined saloon, wholesale whiskey business and grocery store, and eventually took over its management. By 1906 Carmichael had sufficient funds to buy land in an area near Ocala called Silver Springs, shown here. The springs are among the largest artesian spring formations in the world, producing nearly 550 million gallons of crystal-clear water daily. They form the headwaters of the Silver River, a part of the St. Johns River System. Carmichael initially used the site as a steamboat landing for passengers and freight, shown here. At the other end of the steamboat line was Jacksonville, Florida. A railroad spur ran to Ocala.

While still a teenager, Columbus Ed Carmichael, known as “C. Ed,” moved to Ocala, then just a sleepy Florida town, where he helped his father establish a combined saloon, wholesale whiskey business and grocery store, and eventually took over its management. By 1906 Carmichael had sufficient funds to buy land in an area near Ocala called Silver Springs, shown here. The springs are among the largest artesian spring formations in the world, producing nearly 550 million gallons of crystal-clear water daily. They form the headwaters of the Silver River, a part of the St. Johns River System. Carmichael initially used the site as a steamboat landing for passengers and freight, shown here. At the other end of the steamboat line was Jacksonville, Florida. A railroad spur ran to Ocala. At the same time anti-alcohol sentiments were rising in Florida. As an alternative to selling liquor, C. Ed determined to develop Silver Springs into a tourist destination. The old freight depot and other ramshackle buildings were torn down. In their place he constructed a large bathhouse with facilities for men and women. He also built a pavilion at spring side, shown here. Almost single handedly Carmichael had turned Ocala into a tourist destination.

At the same time anti-alcohol sentiments were rising in Florida. As an alternative to selling liquor, C. Ed determined to develop Silver Springs into a tourist destination. The old freight depot and other ramshackle buildings were torn down. In their place he constructed a large bathhouse with facilities for men and women. He also built a pavilion at spring side, shown here. Almost single handedly Carmichael had turned Ocala into a tourist destination.

In 1924, now 61 years old, Carmichael leased his Silver Springs holdings to other entrepreneurs who greatly expanded the tourist facilities he had initiated. Among innovations were glass bottomed boats that floated over the lucid waters allowing people to see more than forty feet to the bottom. Postcards from Ocala often featured the boats with passengers eager to feel the beautiful cool waters. Today Silver Springs is a national landmark, advertised as Florida’s “original attraction.” Thanks to the whiskey man, C. Ed Carmichael.

Note: Longer treatments of each of these individuals can be found on this blog: Edwin S. Hughes, November 23, 2016; Jacob Bergerman, July 18, 2012; Albert Lewin, May 13, 2018; C. Ed Carmichael, December 11, 2016.