Descended from a Dutch ancestor, many of the large DeHart family were settlers in Patrick County, Virginia, a region just east of the Blue Ridge Mountains not far from the North Carolina line. There they engaged in a wide range of businesses, the most lucrative of them making whiskey.

The DeHarts differed little from many of their neighbors. Although some residents avoided taxes by running illegal stills producing “moonshine,” by the 1880s dozens of Blue Ridge stills were operating under state license. A business census of that time listed 54 distillers in Patrick County, but strangely enough, only two saloons. With improved roads and railroads, liquor could be shipped from the region to coal camps, factory towns and larger cities.

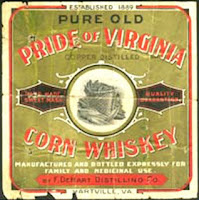

Most of these operations were small. They largely produced limited amounts of brandy from apples or peaches after the fruit harvest. An exception was Fleming DeHart. Born in Patrick County in 1838, Fleming was the son of Thomas DeHart and Martha “Patsy” Via. He apparently had little education and signed legal documents with “x.” A early sign for his distillery above indicates some problems with spelling.

Despite limited book learning Fleming had a wealth of business “horse sense.” He amassed a substantial amount of rich valley farmland and as an adjunct to agriculture started making whiskey from rye and corn. In 1865 he had married Millie Jane DeHart, a distant cousin. The couple produced four children of whom the first, Isaac (Ike), born 1866, and Joseph, born 1870, would walk in their father’s footsteps.

Around 1879 Fleming built large home, shown above in a later newspaper photo. He called his farmstead “Hartville, Virginia.” The location was just his estate and did not appear on Virginia maps. Hartville eventually covered 620 acres and more than 100 people are said to have lived there. In a later newspaper account Fleming was described as a very generous man who welcomed people to his “town.” In time Hartville would even have its own U.S. Post Office, probably to facilitate the shipment of DeHart whiskey.

Around 1879 Fleming built large home, shown above in a later newspaper photo. He called his farmstead “Hartville, Virginia.” The location was just his estate and did not appear on Virginia maps. Hartville eventually covered 620 acres and more than 100 people are said to have lived there. In a later newspaper account Fleming was described as a very generous man who welcomed people to his “town.” In time Hartville would even have its own U.S. Post Office, probably to facilitate the shipment of DeHart whiskey.With prosperity and the coming of age of the two sons the distillery expanded even further and in 1889 was incorporated as the Fleming DeHart Distilling Company. By 1900 Millie Jane DeHart had died and Fleming was sharing his house with Ike and his wife, Mollie. Because Ike was the elder son, he eventually inherited both the farm and the house as his father aged.

The son proved to be every bit the businessman his father had been in managing and expanding the DeHart enterprises. A contemporary article described Ike as farming some of the best land in Virginia, growing fruit and field crops, raising cattle, harvesting lumber, running a grist mill and operating a country store. It added: “DeHart operates a legal still in the area, shipping his products to many parts of the country.” Mollie DeHart was the postmistress of Hartville.

Ike brought more formal education and advertising savvy to the DeHart whiskey business. He began to bottle his whiskey, the better ship it to distant locations. He also hired excellent artists to provide the labels for his liquor. The “Old Ike” brand clearly was a spin-off from his nickname. He also featured well-designed labels for his corn liquor.

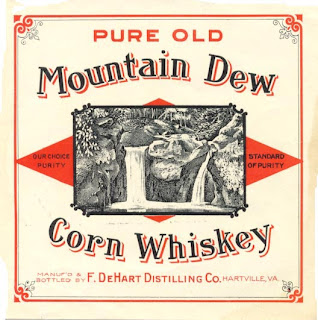

A clear indication of marketing talent was the emphasis on DeHart labels touting the “purity” of the whiskey. What today is called the Pure Food and Drug Act had passed in 1906 and canny distillers picked up the word for merchandising purposes. The purity of DeHart’s "Mountain Dew Corn Whiskey" was emphasized with a waterfall image. As the market for the products of the Fleming DeHart Distillery expanded, the family became increasingly wealthy.

A clear indication of marketing talent was the emphasis on DeHart labels touting the “purity” of the whiskey. What today is called the Pure Food and Drug Act had passed in 1906 and canny distillers picked up the word for merchandising purposes. The purity of DeHart’s "Mountain Dew Corn Whiskey" was emphasized with a waterfall image. As the market for the products of the Fleming DeHart Distillery expanded, the family became increasingly wealthy.Their liquor business stayed strictly legal, annually obtaining Virginia Commonwealth licenses. Later they kept their whiskey in U.S. Government bonded warehouses. Federal records show taxpaying transactions for the distillery almost from the time the “bottled in bond” legislation was passed until Prohibition. Although some of their whiskey was raw enough to be akin to “moonshine,” the DeHarts opted to make it in the sunshine.

The casualty in this success story appears to be Joseph DeHart, the younger brother. Brought up in the distilling business, Joseph found himself as the second son crowded out of the grand inheritance enjoyed by Ike. In 1889, age 26, he married Daisy Via, apparently a cousin. Joseph determined an independent course, not only starting his own distillery but changing the spelling of his name to "de-Hart."

The casualty in this success story appears to be Joseph DeHart, the younger brother. Brought up in the distilling business, Joseph found himself as the second son crowded out of the grand inheritance enjoyed by Ike. In 1889, age 26, he married Daisy Via, apparently a cousin. Joseph determined an independent course, not only starting his own distillery but changing the spelling of his name to "de-Hart." Joseph’s operation was near Woolwine, Virginia, also in Patrick County. He is seen here in an early 1900s ad extolling his liquor, which he called "Mountain Rose Corn Whiskey," a close approximation of his brother's flagship brand. Moreover, his ad may be a slap at his brother, announcing that “I have not made up a dozen or more names for my whiskey and as many prices, which is now so common with the clever whiskey advertising of today....” Joseph’s plain and simple “new” corn whiskey was $2 a gallon and “old,” $2.50.

Joseph’s operation was near Woolwine, Virginia, also in Patrick County. He is seen here in an early 1900s ad extolling his liquor, which he called "Mountain Rose Corn Whiskey," a close approximation of his brother's flagship brand. Moreover, his ad may be a slap at his brother, announcing that “I have not made up a dozen or more names for my whiskey and as many prices, which is now so common with the clever whiskey advertising of today....” Joseph’s plain and simple “new” corn whiskey was $2 a gallon and “old,” $2.50.Despite boasting only two products, Joseph also prospered during the early 1900s. He built a large home near Woolwine. Joseph was keenly aware of the Prohibition pressures in Virginia and when the Commonwealth voted to go dry in 1916, he wrote an ad advising Virginians to lay in a 10 year stock of his corn liquor and “Make Hay While the Sun Shines.”

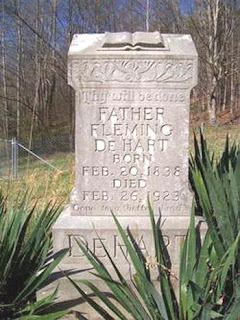

How Brother Ike dealt with the last days of alcohol in Virginia has not been recorded, but his national market base apparently kept the distillery going a year or more beyond 1916. In time the heirs of Ike DeHart, showing the same generous spirit as Fleming, donated family land to Patrick County for a park. A monument stone, shown here, marks the location. Note that it cites the “government distillery” -- a reference to the DeHarts’ strictly legal operation.

How Brother Ike dealt with the last days of alcohol in Virginia has not been recorded, but his national market base apparently kept the distillery going a year or more beyond 1916. In time the heirs of Ike DeHart, showing the same generous spirit as Fleming, donated family land to Patrick County for a park. A monument stone, shown here, marks the location. Note that it cites the “government distillery” -- a reference to the DeHarts’ strictly legal operation.The county park on the site has a range of recreational options but also contains the DeHart family cemetery. Fleming, who died in 1923 shortly after his 85th birthday, has a large grave marker that identifies him as “Father.” Ike with his second wife are buried nearby. Joseph de-Hart, perhaps indicating estrangement from the family, is buried elsewhere.