Although personal information about Simmonds is scant, he is recorded by some sources as having come to California from Boston where he had been in the whiskey trade. My search of census data for him there, however, does not reveal anyone by that name. Moreover, an 1879 ad identified him as “G. Simmonds of Kentucky.” Upon arrival in San Francisco, his age uncertain, George seems immediately to have established a liquor company indicating both experience in the trade and sufficient money to obtain a store and stock it with whiskey and other spirits. He located the business on Montgomery Street, shown below as it looked about that time.

About the time Simmonds arrived on the West Coast, he also was a patented inventor. In March 1877 he applied for and received a patent on “a new and useful improvement on Chamber and Nursery Lamps.” It was a light without a wick that was held in a metal or glass bowl filled with a non-explosive oil. A small upright tube was at the center that rose above the reservoir of oil. A upper opening of the tube was ignited and would remain lighted as the oil rose through the tub until the whole quantity of oil was consumed. Simmonds thought so much of this invention that his 1878 San Francisco business listing was “Nabob Whiskey and Patent Night Light.” Perhaps because the lights did not sell, by the next year the night light reference was gone.

This invention with its application to nurseries may indicate that Simmonds had a family, but there is little evidence to support that idea. He seems to to have avoided the federal census takers during his lifetime. He moved his personal residence frequently, according to directories dwelling at 1719 Howard Street in 1878, 614 O’Farrell in 1880, both likely boarding houses.

From the first, as well, Simmonds seems to have been rectifying whiskey, that is, blending and compounding raw whiskeys to achieve certain smoothness and taste. He was bottling it, putting on his own labels and selling it. Likely needing more space for his operations, he had moved his business to 217 Front Street by 1880. After three years at that location he moved again to 429 Battery, the address on the letterhead above.

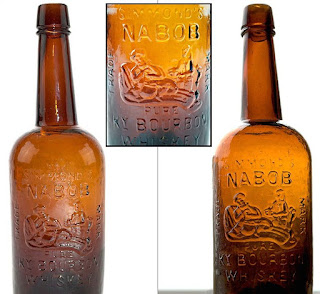

In 1882 Simmons trademarked the name “Nabob” for his brand of whiskey. In his federal application he asserted that the word had been “arbitrarily selected.” Well maybe. Given the images that appeared on Simmond’s labels and bottles, Nabob was an important part of his merchandising strategy. The picture above depicts a large bearded man in a turban and robe, with a hookah pipe and glass in hand. He is being served a bottle of Nabob Whiskey by a servant in a distinctly Moorish setting.

Simmonds had chosen the original meaning of the word, a deputy governor or viceroy of the Mughal Empire rule in India. These were men who lived in comfort and splendor while oppressing the locals. Subsequently the British adopted the term for a conspicuously wealthy Englishman who returned from India with riches gained through corrupt trade. In our own time disgraced Vice President Agnew condemned vocal opponents of the Vietnam War as “nattering nabobs of negativism.”

The Simmond’s company advertised heavily in West Coast publications. Its ads emphasized that Nabob was the “purest and best” for medicinal purposes, claiming that it had been recommended by Dr. H. C. Louderback of St. Louis “in all cases of nervousness, weakness, debility, dyspepsia, indigestion, etc.” Simmonds also provided a testimonial from “the eminent” Dr. S. Dana Hayes, state assayer for Massachusetts. Hayes opined: “The sample marked “Nabob Whiskey,” received from you, has been analyzed with the following results: It is of selected alcoholic strength and free from added flavoring oils, acids, metals, or other deleterious substances. This whiskey is pure, of superior quality, and suitable for dietic and medicinal purposes.”

The Simmond’s company advertised heavily in West Coast publications. Its ads emphasized that Nabob was the “purest and best” for medicinal purposes, claiming that it had been recommended by Dr. H. C. Louderback of St. Louis “in all cases of nervousness, weakness, debility, dyspepsia, indigestion, etc.” Simmonds also provided a testimonial from “the eminent” Dr. S. Dana Hayes, state assayer for Massachusetts. Hayes opined: “The sample marked “Nabob Whiskey,” received from you, has been analyzed with the following results: It is of selected alcoholic strength and free from added flavoring oils, acids, metals, or other deleterious substances. This whiskey is pure, of superior quality, and suitable for dietic and medicinal purposes.”

The image of the nabob was found on Simmonds’ ads, labels and even embossed on the amber glass quarts that held his whiskey. Found frequently by bottle diggers, many are believed to have been made by the San Francisco Pacific Glass Works (1876-1901). The images may differ slightly on these quarts. Below are two Nabob whiskeys, probably bottled at various times and from different batches of containers. In each of the embossings the position of the nabob and the servant differ in relation to the other. In addition, the figure of the nabob varies from bottle to bottle.

On other Simmonds’ bottles, as shown below, the figure of the nabob disappeared completely and just the name of the whiskey was embossed. He also employed other images to advertise Nabob whiskey. Shown here is a trade card in which a young man in medieval dress has doffed his hat to a young woman carrying a cane. The caption mysteriously reads: If you had drunk Simmonds’ Nabob Whisky, I wouldn’t have cared.” George’s other house brands included "Iroquois Whiskey," "Simmonds’ Choice," "Simmonds’ OPS," and "Cream of the Valley Gin."

By 1887, San Francisco business directories were recording that George Simmonds & Co. was being run by other individuals. Among them was Philip Simmonds, his relationship to George unknown. Another was Albert Dallemand, a whiskey man with interests in both San Francisco and Chicago. [See my post on Dallemand, September 2012.] The company was now listed as located at 215-217 California Street. By 1889 the Simmonds Company had disappeared completely from San Francisco directories.

By 1887, San Francisco business directories were recording that George Simmonds & Co. was being run by other individuals. Among them was Philip Simmonds, his relationship to George unknown. Another was Albert Dallemand, a whiskey man with interests in both San Francisco and Chicago. [See my post on Dallemand, September 2012.] The company was now listed as located at 215-217 California Street. By 1889 the Simmonds Company had disappeared completely from San Francisco directories.

I surmise that George Simmonds died in 1896 or 1897 but my attempts to confirm his death and locate his final resting place have been fruitless. Given the many elaborately embossed bottles Simmonds left behind, it is hard to believe that his total career in San Francisco was barely ten years. It is a tribute to his business genius that he was able to make his whiskey a best seller in so short a time and establish his Nabob brand on the liquor shelves of his adopted city, even reaching to the fancy houses of the American nabobs on Nob Hill.

Note: When stymied about components of the personal histories of whiskey men featured here, I frequently seek help from descendants to fill in the blanks. Frequently in the past relatives have stepped forward to provide information and often relevant photographs. Such are always welcome as are suggested corrections. I am hopeful of someone stepping forward and fleshing out the details of George Simmonds’ life.

I have one of these bottles. It has been sitting in my garage for over 35 years. I was throwing it out when I decided to give it a shot on eBay for $0.01. If interested see: http://www.ebay.com/itm/Simmonds-NABOB-Antique-KY-Bourbon-Whiskey-Bottle-/172233778801?hash=item2819eee671:g:elEAAOSwQupXVzUr

ReplyDeleteJohn, I see you made a nice sum on it. I have one I am posting on eBay today. Hope it does as well. 🙂

ReplyDeleteCarol: Good luck! I see too many good items go unbid on eBay because they are priced too high initially. John Newman did not make that mistake. You might do well to follow his example.

ReplyDelete