From modest beginnings, this website now has had more than 1,160,000 views from all over the world. The blog also has received some 2,150 comments, to most of which I have responded. Many have assisted me in correcting or enhancing an original post. The site now has 329 “followers,” to whom I am grateful for their continuing interest.

When I began in 2011, I projected a post every couple of weeks. As the stories multiplied I soon began adding a new vignette every four days, a practice suggested by the continuing flow of good “whiskey men” yarns. That flow has encouraged me to attempt to aim for 1,000 posts by 2023.

At 86 years old, it is hard to look beyond that goal. My plan is to will the entire body of material to the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors for the digital library connected to its online FOHBC Virtual Museum of Historical Bottles and Glass (https://www.fohbc.org › virtual-museum). That way the research represented here can be preserved for the future.

For this 900th post I have chosen the story of Jeremiah Joseph O’Connor of Elmira, New York. Although his story may lack the drama of other whiskey men’s lives, O’Connor epitomizes those individuals who immigrated to the United States, found a career in the liquor trade and went on to help build their communities — and by doing so, America. O’Connor was, in other words, a model whiskey man.

For this 900th post I have chosen the story of Jeremiah Joseph O’Connor of Elmira, New York. Although his story may lack the drama of other whiskey men’s lives, O’Connor epitomizes those individuals who immigrated to the United States, found a career in the liquor trade and went on to help build their communities — and by doing so, America. O’Connor was, in other words, a model whiskey man.

*****

J.J. “Jerry” O’Connor, shown right, was born in Killarney, County Kerry, Ireland, on Christmas Day, 1844, the son of Denis and Mary Reardon O’Connor. Born during the Irish Famine and British suppression his early days may have been ones of poverty. In 1850, at the age of three, his parents emigrated from Ireland to Canada where Jerry grew up and was educated. At age 19, the youth is recorded moving from Whitby, Ontario, to Elmira, New York.

Intelligent and ambitious, O’Conner’s early career included teaching in a Catholic grade school, eventually being raised to principal. His reputed talent as a educator brought him to the attention of the upwardly mobile Irish-American community and other residents. He also found a bride in Elmira, wedding Mary Purcell, a woman of Irish immigrant parents, shown left in middle age. At the time of their 1871 nuptials, according to census data, Jerry was 27 and Mary was 17. Over the next 17 years the couple would have eight children, all of whom seem to have lived to maturity.

Intelligent and ambitious, O’Conner’s early career included teaching in a Catholic grade school, eventually being raised to principal. His reputed talent as a educator brought him to the attention of the upwardly mobile Irish-American community and other residents. He also found a bride in Elmira, wedding Mary Purcell, a woman of Irish immigrant parents, shown left in middle age. At the time of their 1871 nuptials, according to census data, Jerry was 27 and Mary was 17. Over the next 17 years the couple would have eight children, all of whom seem to have lived to maturity.

Perhaps it was the demands of his growing family that spurred O’Connor to leave a career in education and by the early 1870s join an older brother, Dennis, in a liquor business they called O’Connor Brothers, located at 108 Water Street. As an active and articulate Democrat, Jerry also came to the attention of City Hall. When the position of “city chamberlain” was created in 1876, O’Connor was the first appointee. The chamberlain was Elmira’s chief fiscal officer, custodian of all city funds and responsible for general accounting functions. O’Connor proved an inspired choice. As the initial holder of the office it fell to him to devise systems for accounts payable, payroll, budget monitoring, investing city funds, financial reporting, and collection of real estate taxes. Accord to a biographer, O’Connor “put the financial system in shape” and his methods were maintained long after he left the post in 1879.

That move almost certainly was occasioned by the sickness and death of his brother, Dennis in February 1879. Now Jerry had full responsibility for the liquor house. In time he changed the name to “Jeremiah J. O’Connor - Wholesale Liquor and Wine.” To customers like saloons, restaurant and hotels, he was providing whiskey obtained by the barrel, decanted on premises and sold in ceramic jugs. His early containers, obtained from the W. Farrington pottery of Elmira, were graced by attractive decoration, as below. In time, he moved to more utilitarian jugs, as shown below.

Like many whiskey wholesalers O’Connor marketed his own proprietary brand of whiskey, called “Walton.” This liquor would have been supplied to him by a nearby distillery to a recipe he dictated or, more likely, blended on his premises. A practice in the trade was to reward special customers with items such as shot glasses advertising such house brands. O’Connor’s giveaway was particularly stylish. As business flourished he relocated to larger quarters at 414-416 Carroll Street.

Like many whiskey wholesalers O’Connor marketed his own proprietary brand of whiskey, called “Walton.” This liquor would have been supplied to him by a nearby distillery to a recipe he dictated or, more likely, blended on his premises. A practice in the trade was to reward special customers with items such as shot glasses advertising such house brands. O’Connor’s giveaway was particularly stylish. As business flourished he relocated to larger quarters at 414-416 Carroll Street.

In the meantime O’Connor’s ability and accomplishments had advanced him to major roles in the Democratic Party. Following an appointment to the Elmira Board of Heath for two years, he was put forward as the Democratic candidate for the New York General Assembly in 1883. He won and served two terms, during which his talent as “a public speaker of no mean ability” brought him notice. At the 1885 state Democrtic convention, O’Connor was chosen to place the party candidate for governor in nomination, a singular tribute to his eloquence.

In the meantime O’Connor’s ability and accomplishments had advanced him to major roles in the Democratic Party. Following an appointment to the Elmira Board of Heath for two years, he was put forward as the Democratic candidate for the New York General Assembly in 1883. He won and served two terms, during which his talent as “a public speaker of no mean ability” brought him notice. At the 1885 state Democrtic convention, O’Connor was chosen to place the party candidate for governor in nomination, a singular tribute to his eloquence.

Much of this whiskey man’s attention was directed toward the Ireland of his heritage, primarily through his role in the U.S. chapter of the Irish Land League, an organization to protect Irish farmers from capricious evictions by British landlords. Through peaceful means the League sought to establish “three F’s”: fair rent, fixity of tenure, and free sale of the right of occupancy. O’Connor was a member of the U.S. Executive Committee, and its treasurer who raised the equivalent in today’s dollar of over $400,000 for the poor in Ireland.

O’Connor’s growing wealth from liquor sales also allowed him to make outside investments. In 1885 he was among the Elmira businessmen who founded the Elmira Daily Free Press, a newspaper that survived for 22 years before being merged with another publication. He also was president of the Grand Forks North Dakota Land and Investment Co. Thousands of settlers had been attracted to the Dakota Territory in the 1870s and 1880s for its cheap land. Companies like O’Connor’s helped settlers established small family farms.

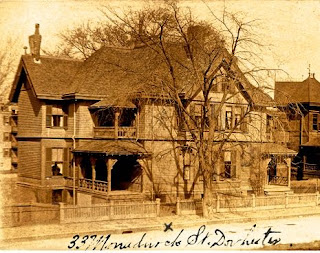

Financial interests increasingly called O’Connor to New York City. There in 1910, he fell down the steps of a Manhattan subway and was severely injured. When the damage proved permanently disabling, he directed the 1912 incorporation of the Jeremiah J. O’Connor liquor company. As directors he appointed his wife Mary and one of his sons, 23-year-old Charles Borromeo O’Connor. Aware that his injuries might lead to complete incapacity or death, Jerry wisely had looked to the future. It was not long in coming. He died on November 23, 1913, at the age of 68 and was buried in Elmira’s St. Peter and Paul Cemetery. His headstone is shown here.

Financial interests increasingly called O’Connor to New York City. There in 1910, he fell down the steps of a Manhattan subway and was severely injured. When the damage proved permanently disabling, he directed the 1912 incorporation of the Jeremiah J. O’Connor liquor company. As directors he appointed his wife Mary and one of his sons, 23-year-old Charles Borromeo O’Connor. Aware that his injuries might lead to complete incapacity or death, Jerry wisely had looked to the future. It was not long in coming. He died on November 23, 1913, at the age of 68 and was buried in Elmira’s St. Peter and Paul Cemetery. His headstone is shown here.

O’Connor’s death merited front page headlines in the Free Press and other Elmira publications. Hailed as a “notable Elmiran,” his obituaries celebrated the life of an immigrant who had contributed significantly to the development of the city. His liquor house continued on after his death with the widowed Mary as vice president and treasurer, Charles as secretary, and a non-family member as manager. After 1917 the O’Connor liquor house disappeared from Elmira directories.

Note: The major source of this post were from an internet copy of the book, “A History of the Valley and County of Chemung,” by Ausburn Towner, dated 1892. Brief quoted material is from that history. That resource was supplemented by Elmira newspaper stories and genealogical websites.