Recently the Louisiana State University Press announced it would be publishing a new series of short books on famous cocktails. Because LSU is not likely to treat a libation that primarily sold in a bottle, it occurred to me that a post on an drink marketed nationally before Prohibition by Boston liquor dealer Chester H. “Chet” Graves also deserves to have its history revealed. The libation was known as “Hub Punch.

Recently the Louisiana State University Press announced it would be publishing a new series of short books on famous cocktails. Because LSU is not likely to treat a libation that primarily sold in a bottle, it occurred to me that a post on an drink marketed nationally before Prohibition by Boston liquor dealer Chester H. “Chet” Graves also deserves to have its history revealed. The libation was known as “Hub Punch.

”Hub Punch did not originate in Boston, however, but on Hub Island, a small bit of land in the St. Lawrence River, located between Grenell Island and Thousand Island Park, shown on the map above. The dominant feature of the island was the Hub House, right. That hotel has been described as a “debaucherous” lodging, dance hall and bar. A short boat ride from the mainland, it was notorious for its dance parties at which young people could waltz until dawn, sleep in one of the rooms, and dance the next night through, all the while imbibing their favorite cocktails.

”Hub Punch did not originate in Boston, however, but on Hub Island, a small bit of land in the St. Lawrence River, located between Grenell Island and Thousand Island Park, shown on the map above. The dominant feature of the island was the Hub House, right. That hotel has been described as a “debaucherous” lodging, dance hall and bar. A short boat ride from the mainland, it was notorious for its dance parties at which young people could waltz until dawn, sleep in one of the rooms, and dance the next night through, all the while imbibing their favorite cocktails.

The most popular of those alcoholic concoctions was known as Hub Punch. It was the brain child of an Oswego, New York, bartender named Bart Keether, who was in charge of the Hub House bar and the first to mix Hub Punch. The drink was an instant hit, according to one author. Although Keether served it during the 1870s and into the 1880’s, he never divulged his recipe. Some have speculated that among its ingredients were rum and brandy. The end of Keether’s punch came in 1883 when Hub House burned to the ground.

Chet Graves was not about to let the popularity of Hub Punch fade away. In 1858, Oliver Wendell Holmes had identified Boston as “The Hub of the Solar System,” which developed into “The Hub of the Universe” or just “The Hub City.” Hub Punch fit well with Boston. Graves added it to the flurry of proprietary brands of liquor he offered.

Those whiskeys included: "Beech Grove,” "Boat Club,” "Cumberland Club,” "Graves' Maryland Malt,” "Kentucky Union,” "Mackinaw Rye,”Old Heritage Rye,” “Superba,” "The Judges Favorite,” "Union League Club,” and "Walnut Hill Pure Rye.” He trademarked Walnut Hill Rye, likely his flagship whiskey, in 1892. After Congress strengthened trademark protections in 1905, Graves registered many of his other brands.

On May 1, 1879,C. Graves & Sons advertised: “At the earnest solicitation of a number of our hotel patrons and personal friends we have decided to offer our Rum and Brandy Punch in bottles, an article that has a most excellent reputation, having been originally prepared by our senior member.” Graves appeared to be taking credit for the origins of Hub Punch. Observers generally agree that his recipe, also never divulged, differed from Keether’s but do not know how. Grave’s ads give slim clues to its contents, claiming to contain “only the best of liquors, choice fruit juices and granulated sugar.” Ads also suggested “drinking clear or mix with lemonade, soda or ice water.” Because it was sold before National Prohibition, Hub Punch was not required to disclose its alcoholic content.

On May 1, 1879,C. Graves & Sons advertised: “At the earnest solicitation of a number of our hotel patrons and personal friends we have decided to offer our Rum and Brandy Punch in bottles, an article that has a most excellent reputation, having been originally prepared by our senior member.” Graves appeared to be taking credit for the origins of Hub Punch. Observers generally agree that his recipe, also never divulged, differed from Keether’s but do not know how. Grave’s ads give slim clues to its contents, claiming to contain “only the best of liquors, choice fruit juices and granulated sugar.” Ads also suggested “drinking clear or mix with lemonade, soda or ice water.” Because it was sold before National Prohibition, Hub Punch was not required to disclose its alcoholic content.

Marketed through vigorous advertising in local newspapers and national magazines, Hub Punch proved to be a hit with the American drinking public. Increasingly people were moving from straight liquor to cocktails and mixed drinks. Hub Punch suited the trend well. As shown below, Graves packaged his beverage in both clear and amber quart bottles, bearing blue or green labels that depicted the skyline of Hub City.

Marketed through vigorous advertising in local newspapers and national magazines, Hub Punch proved to be a hit with the American drinking public. Increasingly people were moving from straight liquor to cocktails and mixed drinks. Hub Punch suited the trend well. As shown below, Graves packaged his beverage in both clear and amber quart bottles, bearing blue or green labels that depicted the skyline of Hub City.

Graves’ rise to success in the liquor trade was a long one. He was born in Sunderland, Massachusetts, in January 1818, the son of Eliza Hatch and Elijah Graves, a New England family whose Yankee ancestry stretched back into colonial days. He arrived in Boston in 1844 at age 24 and went to work for Seth W. Fowle, a manufacturer and dealer in patent medicines, known for his inventive advertising for his lung remedies, including the highly alcoholic “Wistar’s Balsam of Wild Cherry.”

After four years of working for Fowle and learning his merchandising techniques, Graves moved on to the Boston house of John T. Hearn where he spent the next 12 years engaged in the liquor trade. In November 1846 he married Charlotte A. “Lottie” Fuller of Newton, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb. Although sources differ on numbers, the couple had at least three sons and a daughter over the next 14 years.

His growing family may have induced Graves to strike out on his own. In time he brought his two eldest boys, Edward and George, into the business, and it became Chester H. Graves and Sons. Graves continued to guide the fortunes of his company until his death in April 1901 at the age of 82. His sons took the reins of management and continued the success of Hub Punch until closed by the advent of National Prohibition in 1920.

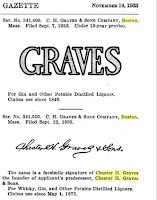

Unlike the great majority of liquor houses in America that closed for good, the Graves boys waited out the “dry” 14 years and in 1933 as Repeal became certain trademarked the name and signature of their father. The application reads “for gin and other potable liquors.” A bottle of the company’s gin is shown right. I have not found evidence that the sons revived Hub Punch in the post-Prohibition era.

Unlike the great majority of liquor houses in America that closed for good, the Graves boys waited out the “dry” 14 years and in 1933 as Repeal became certain trademarked the name and signature of their father. The application reads “for gin and other potable liquors.” A bottle of the company’s gin is shown right. I have not found evidence that the sons revived Hub Punch in the post-Prohibition era.

In more recent times, however, a brother team in Boston has brought new life to Hub Punch. Will and Dave Willis in 2010 founded Bully Boy Distillers, Boston’s first craft distillery. They specialize in making small batch spirits in accord with local tradition and recognized that historically no beverage was more closely identified with Boston than Hub Punch. As for ingredients, the Bully Boy version is not identical either to Keether’s or Graves’ recipe. The bottle says only that it is “infused with orange, fruits and botanicals” and is 70 proof, that is, alcohol just over one-third of the volume. As is said, things old thus are made new again.

Note: This post and illustrations was gathered from a variety of Internet sources, among them a 2014 article from MISE magazine by Cassandra Landry.