In profiling more than 950 “whiskey men” — distillers, dealers, and saloonkeepers — I cannot recall dealing previously with a Swedish family involved in the liquor trade, nor one in which a father worked for his children. That made the discovery of the Sandells of St. Paul, Minnesota, all the more fascinating.

Shown here, Nels Sandell was born in January 1845 in Fryksande, Varmland, Sweden, a bucolic area boasting large three lakes, shown below. His father, Nils Sandhall, was a farmer who also kept an inn on his land. Under government regulation regarding service and prices, the inn was a traveler’s “public utility” in a region that had no railroad. It provided lodging, board, and transportation to the next hostelry in the network. Working in the inn from childhood, Nels received a typical education for a Swedish youth, served the required two years in the Swedish army and for a short time ran a general store.

Shown here, Nels Sandell was born in January 1845 in Fryksande, Varmland, Sweden, a bucolic area boasting large three lakes, shown below. His father, Nils Sandhall, was a farmer who also kept an inn on his land. Under government regulation regarding service and prices, the inn was a traveler’s “public utility” in a region that had no railroad. It provided lodging, board, and transportation to the next hostelry in the network. Working in the inn from childhood, Nels received a typical education for a Swedish youth, served the required two years in the Swedish army and for a short time ran a general store.

In 1866 he married his childhood sweetheart, Carolina Jonsdotter Westburg, in Fryksande. Nels was 21; Carolina was 17. His marriage apparently provided the incentive for the newlyweds to leave their native land for America, arriving in 1868 while Carolina was pregnant with their first child. They headed for Minnesota, a state that was known for its large Scandinavian population.

Their initial destination was Jordan, a small town south of Minneapolis, a town with a proliferation of breweries. There Nels, having “Americanized” his name to Sandell, opened a general store. Among his stock was liquor. After operating the store for more than a decade during which Jordan’s population grew only slightly, Nels “looked up the road” 44 miles to St. Paul and with Carolina, their four sons and three daughters, moved there.

Nels initial activity, according to business directories, was operating a saloon at 373 East Seventh Street. His family lived above the establishment. As time elapsed, the father began to take his sons into the liquor trade and gradually retreated into the background. By 1897 the family drinking establishment had become the George Sandell Saloon, named for his oldest son. Nels was listed as “manager.” By 1900, two other Sandell sons had joined George, shown left. Oscar was listed as a salesman, indicating that the saloon had a retail trade; Albert, right, was the bookkeeper.

Nels initial activity, according to business directories, was operating a saloon at 373 East Seventh Street. His family lived above the establishment. As time elapsed, the father began to take his sons into the liquor trade and gradually retreated into the background. By 1897 the family drinking establishment had become the George Sandell Saloon, named for his oldest son. Nels was listed as “manager.” By 1900, two other Sandell sons had joined George, shown left. Oscar was listed as a salesman, indicating that the saloon had a retail trade; Albert, right, was the bookkeeper.

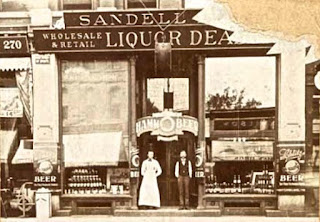

By 1905, the saloon was gone and the Sandells were doing business as “Sandell Brothers, Importers and Wholesale Dealers in Wines and Liquors.” The letterhead above indicates that the CEO was George, then 34, aided by Oscar, 32, and Albert, 27. Nels was listed as traveling salesman for the company. A photo of their establishment shows a well-stocked front window as well as signs advertising Hamm’s and Schlitz beer. It is impossible to identify the standing figures but they may be two of the Sandells.

The brothers’ proprietary whiskey brands included "Milton", "Nordey Club", "Norden Club Rye", "Sidney Private Stock", "Snelling Rye", “Woodbridge,” and “Old Monogahela.” The only brand they trademarked was “Nordey Club”(1906). The Sandells also featured a “Norden Bitters” along with their whiskeys. The Norden Club was a athletic and social organization for Swedes and other Scandinavians, to which Nels and other family members belonged.

The brothers’ proprietary whiskey brands included "Milton", "Nordey Club", "Norden Club Rye", "Sidney Private Stock", "Snelling Rye", “Woodbridge,” and “Old Monogahela.” The only brand they trademarked was “Nordey Club”(1906). The Sandells also featured a “Norden Bitters” along with their whiskeys. The Norden Club was a athletic and social organization for Swedes and other Scandinavians, to which Nels and other family members belonged.

Sandell Bros. was a blender of whiskeys that were sold in gallon or more quantities to saloons, restaurants and hotels. Those wholesale customers would then decant them into smaller containers for use by their bartenders. The jugs then might have been returned to the Sandell’s liquor house for cleaning and refilling.

Those jugs can be identified as products of potteries in Red Wing, Minnesota, a town on the Mississippi River less than fifty miles from St. Paul. Made to order for distillers and liquor houses throughout the Midwest these containers are noted for their clean lines and tasteful labels. Like the one shown right, the labels were applied using a inked rubber stamp, fired, and a clear overglaze applied, a process requiring considerable precision. Because of their quality, Red Wing-made whiskey jugs today can fetch into the thousands of dollars from collectors.

Two of the Sandell brothers became family men. George was married in June 1903 to Margaretta Aurillia Baier, a childhood friend from his years in Jordan. The newlyweds are shown here. By the 1910 census they would have two children, Urana Alice, 5, and George Albert, 2. Oscar also married, his bride was Anna S. Grote of St. Paul. By 1910 this couple was recorded as having two children, Ethel born in 1904 and Paul in 1905. The census year found Nels, 64, still working as a traveling salesman for his sons, living the spacious home shown below. The household included his wife, Caroline, and four unmarried adult children, including Albert and Anna, who was working for Sandell Bros. as a bookkeeper. The first decade of the 20th Century was good to the Sandell clan.

Two of the Sandell brothers became family men. George was married in June 1903 to Margaretta Aurillia Baier, a childhood friend from his years in Jordan. The newlyweds are shown here. By the 1910 census they would have two children, Urana Alice, 5, and George Albert, 2. Oscar also married, his bride was Anna S. Grote of St. Paul. By 1910 this couple was recorded as having two children, Ethel born in 1904 and Paul in 1905. The census year found Nels, 64, still working as a traveling salesman for his sons, living the spacious home shown below. The household included his wife, Caroline, and four unmarried adult children, including Albert and Anna, who was working for Sandell Bros. as a bookkeeper. The first decade of the 20th Century was good to the Sandell clan.

The year 1910, however, brought sorrow as George died in August at the age of 39. He left behind his widow, Margaretta, and their two young children. Under the watchful eyes of Nels, Oscar ascended to the presidency of Sandell Brothers. Albert became secretary-treasurer. Walter, the youngest Sandell, joined the company, listed as a clerk. Shown here, by 1915 he would be raised to the position of vice president.

The year 1910, however, brought sorrow as George died in August at the age of 39. He left behind his widow, Margaretta, and their two young children. Under the watchful eyes of Nels, Oscar ascended to the presidency of Sandell Brothers. Albert became secretary-treasurer. Walter, the youngest Sandell, joined the company, listed as a clerk. Shown here, by 1915 he would be raised to the position of vice president.

With the coming of National Prohibition, the Sandells were forced to shut down their liquor house. According to business directories, Oscar became a salesman for a cider company and Albert moved to Forest Lake, Minnesota. Walter took over the East Seventh Street space and turned the liquor house into a restaurant and bottler of soft drinks.

At 75 years old Nels retired. He lived another nine years, dying on January 7, 1929. Following services at St. Sigfrid’s Swedish Episcopal Church, he was buried in St. Paul’s Oakland Cemetery beside Carolina who had died nine years earlier. Oscar and Walter are interred nearby. A monument marks the family plot.

At 75 years old Nels retired. He lived another nine years, dying on January 7, 1929. Following services at St. Sigfrid’s Swedish Episcopal Church, he was buried in St. Paul’s Oakland Cemetery beside Carolina who had died nine years earlier. Oscar and Walter are interred nearby. A monument marks the family plot.

Of Nels an observer wrote: “He is an energetic and keen businessman and conducts his affairs with integrity and honest dealing.” To that praise I would add — “And a father whose mind and heart was dedicated to the advancement of his children.”

Note: A key reference for this post was “A History of the Swedish-Americans of Minnesota,” by Algot E. Strand, published in 1910. Other information was furnished by St. Paul directories and genealogical sites.