Let’s set the stage. Shown below are pictures of the principals. Left is Mary Agnes Maloney, a pretty young woman, 19, of Irish Catholic heritage. At right is Joseph D. Sattler, 24, a dapper young Jewish immigrant from Bohemia. They had met in Duluth, fallen deeply in love, but found their families adamantly opposed to their marriage. It was a “Romeo and Juliet” story set in the Upper Midwest. What were the lovers to do?

The setting and dialogue for this melodrama was provided by a Duluth newspaper in January 1891 under the headline: “An Elopement That Causes a Sensation in Two Duluth Families.” The news story related the scene: “About a week ago two young ladies sat in their room. One was tall and beautiful [Mary Agnes], the other of medium height and rustic beauty. The soft glow of a shaded light lit the room, and the two fair intruders chatted in a whisper. The taller of the two was in the house of her parents, while her companion was a visitor from Dakota.”

“‘Will I do it?,’ impulsively asked the Duluth girl. ‘You should. You will not be the first girl that ran away and got married, and as you know, I think it is so romantic and just too lovely for anything to run away with a lover. And then too, when it gets in the paper it makes such charming reading. I think all such marriage quite cute. You could come to our home in Dakota and everything could take place. Then you could write home and tell them all. Yes, do run away.’”

“Her companion did not speak, but a quiet smile played about her mouth. After a while she said: ‘Well I love him, although my Ma doesn’t. But Ma can’t understand that we love differently now from what they did in her time.’” Thus were the plans for the elopement hatched. On the pretext of a simple visit to the Dakota girl’s home in Grand Forks, Mary Agnes contacted Joseph to meet her there. Working in his uncle’s Duluth store, Joseph announced he was going to Chicago for a holiday. Instead the young man hurried to Grand Forks.

Although the wedding initially was to take place in a home, the marriage license above indicates the ceremony occurred on January 13, 1892, in Grand Fork’s St. Michael’s Catholic Church, conducted by the pastor, Father Edward Conaty. When the word reach the couple’s families in Duluth, the newspaper reported” “There was war all around today, and the young couple may be allowed to repent at leisure. Most of the hostility comes from the fact that Joe is a Hebrew and his wife a gentile of the Roman Catholic persuasion.”

Despite an inauspicious start to the marriage when Sattler was forced to wire relatives for money just to bring his new bride and himself back to Duluth from Grand Forks, the groom was a young man with ambition and prospects. Born in Radkovnik in 1868 in the Bohemian section of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Sattler at about nine years had immigrated into the United States, arriving in New York City with family members aboard the Steamship Oder, shown here.

Despite an inauspicious start to the marriage when Sattler was forced to wire relatives for money just to bring his new bride and himself back to Duluth from Grand Forks, the groom was a young man with ambition and prospects. Born in Radkovnik in 1868 in the Bohemian section of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Sattler at about nine years had immigrated into the United States, arriving in New York City with family members aboard the Steamship Oder, shown here.

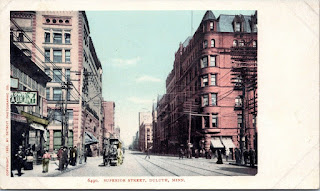

After receiving his education in New York schools, by 1890 Sattler moved to Minnesota to go to work as a clerk in a major Duluth department store owned by his uncle, Ignatz Freimuth. Shown here, the store was one of the city’s largest and most prosperous, offering the young immigrant opportunities for advancement. Instead, following his marriage and its new familial responsibilities, Sattler began planning to strike out on his own. By 1902, he had achieved sufficient resources to open a liquor house at 20 East Superior Street, below, in the Duluth business district. He called it “Sattler Liquor Company, Importers, Distillers, Wholesale Liquor Dealers.” His flagship brand was SaddleRock Whiskey.

After receiving his education in New York schools, by 1890 Sattler moved to Minnesota to go to work as a clerk in a major Duluth department store owned by his uncle, Ignatz Freimuth. Shown here, the store was one of the city’s largest and most prosperous, offering the young immigrant opportunities for advancement. Instead, following his marriage and its new familial responsibilities, Sattler began planning to strike out on his own. By 1902, he had achieved sufficient resources to open a liquor house at 20 East Superior Street, below, in the Duluth business district. He called it “Sattler Liquor Company, Importers, Distillers, Wholesale Liquor Dealers.” His flagship brand was SaddleRock Whiskey.

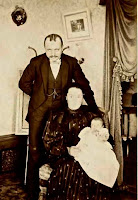

Meanwhile on the home front, the marriage of Joseph and Mary Agnes seemed to move smoothly as their respective families eventually came to accept the reality of their union. Although their first child, a boy, died at after one month in 1893 and was buried in the Catholic cemetery, a healthy girl was born in June 1897. A family photo shows the couple with their new daughter, Marie Therese. A son, Arlayne, was born in 1905.

Meanwhile on the home front, the marriage of Joseph and Mary Agnes seemed to move smoothly as their respective families eventually came to accept the reality of their union. Although their first child, a boy, died at after one month in 1893 and was buried in the Catholic cemetery, a healthy girl was born in June 1897. A family photo shows the couple with their new daughter, Marie Therese. A son, Arlayne, was born in 1905.

Sattler’s liquor house appears rapidly to have been successful. He was able to give employment to his brothers. Jacob B. Sattler was named treasurer and Emanuel Sattler vice president. Outgrowing the Superior Street location, he moved his liquor business to 214-216 West Michigan Street into a three story building that also contained a cigar company on the third floor.

The future, however, would bring setbacks. In January 1906 a fire of unknown origin broke out on the second floor, occupied by Sattler. Quick action by the Duluth Fire Department limited damage to the liquor house. The greatest damage occurred to an elevator shaft and stairway on the second floor and the third floor. It wiped out the cigar company. The loss to Sattler was estimated at $15,000 (today close to a half million dollars), said to be fully covered by insurance.

That setback was followed two months later by a robbery committed by a very unusual burglar, identified as Albert Schultz, 24. When arrested Schultz was carrying a letter apparently intended for Joseph Sattler. According to press accounts, in it the burglar “expressed dissatisfaction that the Sattler Liquor Company’s champagne stock was depleted before he got around.” That revelation drew laughs from the grand jury that then indicted him on a second degree burglary charge. Schultz pled guilty and went to jail.

In June 1907, the marriage that had caused Duluth headlines came to a halt after 16 years with the Mary Agnes’ untimely death at age 35. Earlier the press had noted her ill with quinsy (strep throat). Indicative that consternation over her marriage had abated, local press reported that she visited often with relatives and: “Her death will be mourned by a wide circle of friends.” She was buried in Duluth’s Catholic cemetery adjacent to her infant son.

In June 1907, the marriage that had caused Duluth headlines came to a halt after 16 years with the Mary Agnes’ untimely death at age 35. Earlier the press had noted her ill with quinsy (strep throat). Indicative that consternation over her marriage had abated, local press reported that she visited often with relatives and: “Her death will be mourned by a wide circle of friends.” She was buried in Duluth’s Catholic cemetery adjacent to her infant son.

In 1909, possibly wanting a mother for his 12-year-old daughter, Marie, and 5-year old son, Arlayne, Sattler remarried at age 40. His second wife was Jewel A. Sattler, a Michigan-born woman. The 1910 census found the family living on East 9th Street in Duluth with a servant and a boarder. The house is shown here as it looks today. A genealogical site indicates that Sattler may have wed a third time, a woman named “Minnie,” but I can find no evidence of the marriage.

In 1909, possibly wanting a mother for his 12-year-old daughter, Marie, and 5-year old son, Arlayne, Sattler remarried at age 40. His second wife was Jewel A. Sattler, a Michigan-born woman. The 1910 census found the family living on East 9th Street in Duluth with a servant and a boarder. The house is shown here as it looks today. A genealogical site indicates that Sattler may have wed a third time, a woman named “Minnie,” but I can find no evidence of the marriage.

In 1915, after some 13 years in the liquor trade, Sattler declared bankruptcy and shut the doors on his business. Not long after, accompanied by his family, he moved to Wisconsin as an executive of the Milwaukee Knitting Mill Company. In June 1916 Sattler died there at the age of 48. Although reported to have been in bad health, the immediate cause of his death was not reported. Sattler’s body was returned to Duluth where he was buried in Temple Emanuel Cemetery.

The difference in religious affiliation that had made the elopement of Mary Agnes and Joseph a newsworthy sensation in Duluth in 1891 by all appearances had not been a major problem in the Sattlers’ married life. In death the difference did. Mary Agnes is buried in a Duluth Catholic cemetery, Joseph is interred in the Jewish burying ground. Several miles separate their graves.

Notes: This post would have been impossible without a website entitled “Old Newspaper Articles: The Sattler Family,” a chronological list of articles culled from the pages of Duluth newspapers by descendants. The site includes more than a dozen articles related to Joseph and Mary Agnes, including the one that opens this post.