Shown here on a passport photo, Ralph Lewis Spotts overcame a less than illustrious beginning in Canton, Ohio, to win gold twice in his life, once at the end of a shotgun at the 1912 Olympic Games and later by inheriting through marriage one of New York City’s best known and most affluent liquor houses.

Shown here on a passport photo, Ralph Lewis Spotts overcame a less than illustrious beginning in Canton, Ohio, to win gold twice in his life, once at the end of a shotgun at the 1912 Olympic Games and later by inheriting through marriage one of New York City’s best known and most affluent liquor houses.

Spotts was born in June 1875, the eldest son of Daniel and Emma Spotts. His father was recorded in the 1870 census living in Lenawee, Michigan, and working in a factory there making barrel staves. At some point Daniel moved to Canton and an 1891 business directory records him as manager of the “Lippy Cash & Package Co.” Meanwhile Ralph, 16, was going to school. Two years later Daniel had left Lippy and now owned of a Canton enterprise called “The Big Bargain Store.” Ralph, having just finished secondary school, was working there.

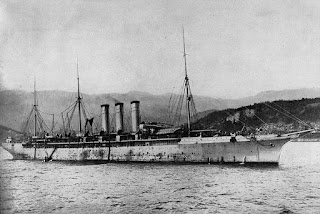

By 1898, The Big Bargain Store was defunct, but another opportunity was presented to Ralph by the Spanish-American War. Already recognized widely for his ability with a gun, Spott’s enlisted in the 8th Regiment of the Ohio Voluntary Army, known as “McKinley’s Own,” for the Ohio-born President. The 23-year-old was eagerly accepted in Company I and accorded the rank of first sergeant. After brief basic training at Camp Alger, Virginia, the Ohio 8th, shown here, embarked on the U.S.S. Yale, below, for Cuba.

By 1898, The Big Bargain Store was defunct, but another opportunity was presented to Ralph by the Spanish-American War. Already recognized widely for his ability with a gun, Spott’s enlisted in the 8th Regiment of the Ohio Voluntary Army, known as “McKinley’s Own,” for the Ohio-born President. The 23-year-old was eagerly accepted in Company I and accorded the rank of first sergeant. After brief basic training at Camp Alger, Virginia, the Ohio 8th, shown here, embarked on the U.S.S. Yale, below, for Cuba.

The regiment saw hot combat around the Cuban cities of Siboney and Santiago but most casualties and deaths were as the result of disease. One Ohio newspaper extolled the regiment as having “established itself forever in the hearts of its townsmen and citizens of Ohio, who will recite its deeds and bravery for years to come.” Certainly Spotts had distinguished himself. In August 1898 he was promoted to captain and made adjutant to a general.

The next several years of Spott’s life have gone largely unrecorded. Discharged from the Army, over the next several months he met and wooed Josepha Kirk. She was the daughter of one of New York City’s true “whiskey barons,” Harford Kirk, the man who had promoted “Old Crow” to a top whiskey seller. The record is blank, however, on how Ralph met Josepha. Canton is a long way from New York City and the social classes of the two were distinctly different.

Nonetheless, marry they did in 1900. The federal census that year found the couple living in Canton where Spotts was recorded working in a hardware store. Their first of three children, Ralph Lewis Spotts Jr., was born in Canton. Not long after, however, all three Spotts moved to New York City. My assumption is that Josepha’s parents wanted the family closer at hand and Harford Kirk had ideas for Ralph’s future that did not include selling paint and hardware.

Likely with a strong boost from Harford Kirk financially, Spotts entered the highly competitive New York City whiskey and wine trade. Business directories of the time record him working at Kirk headquarters at 146 Franklin Street. In a 1906 corporate reorganization of the H. B. Kirk Company, his father-in-law made him a director.

The 1910 census found the Spotts living in an upscale New York neighborhood. Their household now included two more children, Dorothy 4 and Robert 2, along with five live-in servants, four women and a man. By now they were living in a mansion. Purchased by Spotts for the equivalent today of $2.5 million, he then spent more thousands adding a two story addition to the rear roof.

Spott’s reputation won him a place on the 1912 Summer Olympics trap shooting team representing the United States. For years this competition had been dominated by the British, Germans and French. The American team seemingly was not accounted a major competitor. Before embarking for Europe, the team posed for a group photo at the New York Athletic Club. I believe that Spotts is the man standing second from the right.

Spott’s reputation won him a place on the 1912 Summer Olympics trap shooting team representing the United States. For years this competition had been dominated by the British, Germans and French. The American team seemingly was not accounted a major competitor. Before embarking for Europe, the team posed for a group photo at the New York Athletic Club. I believe that Spotts is the man standing second from the right.

At the site of the games in Stockholm, Sweden, pundits were increasingly skeptical of the American chances. Olympic rules demanded that the shotgun be held below the armpit. The Yanks were accustomed to raising it higher. Moreover, in Stockholm competitors would be allowed to fire both barrels at the moving targets, something not allowed in U.S. competitions. Several days of practice in these modes, however, gave the American team renewed confidence they could shoot with the same ease as with their accustomed style.

At the site of the games in Stockholm, Sweden, pundits were increasingly skeptical of the American chances. Olympic rules demanded that the shotgun be held below the armpit. The Yanks were accustomed to raising it higher. Moreover, in Stockholm competitors would be allowed to fire both barrels at the moving targets, something not allowed in U.S. competitions. Several days of practice in these modes, however, gave the American team renewed confidence they could shoot with the same ease as with their accustomed style.

When the competition ended on July 2, 1912, the Americans had captured the world team trapshooting title. With their captain shooting 94 of the 100 clay pigeons presented and no member hitting fewer than 80, the team shattered 532 of 600 targets. The British trailed at 511 and the Germans at 510. Spotts had distinguished himself by scoring 90 of 100. New York sports writers were quick to hail the win as “accomplish with American guns, shells, and powder” and of “arousing great enthusiasm” among both foreign and American spectators. The win also inspired a political cartoonist to fervent heights of nationalism.

Not only did Spotts come back to wife and family bearing a gold medal, he and the team were honored in a parade of U.S. Olympic medal winners down Fifth Avenue as fans packed the streets. For years afterward Spotts’ name appeared in sporting magazines like Field & Stream as he continued to add silver cups and trophies for his prowess as a marksman.

Not only did Spotts come back to wife and family bearing a gold medal, he and the team were honored in a parade of U.S. Olympic medal winners down Fifth Avenue as fans packed the streets. For years afterward Spotts’ name appeared in sporting magazines like Field & Stream as he continued to add silver cups and trophies for his prowess as a marksman.

Upon returning to New York Spotts assumed a heavy work load. After a period of declining health, Harford Kirk died in July 1907 leaving the day-to-day management of the liquor house to Spotts, now moved to vice-president. In addition, the son-in-law was the executor of Kirk’s estate. Spotts also was recorded as the president of the Walton Hotel, a New York apartment hotel, and as a partner in the Cantono Electric Tractor Company.

Advanced to president of H. R. Kirk Company, Spotts purchased the 156 Franklin Street headquarters building outright and continued to grow the business. As before, the aggressive marketing of Old Crow Whiskey was a principal activity. He also continued Kirk’s strategy of copious advertising, including a patriotic message during World War One.

Advanced to president of H. R. Kirk Company, Spotts purchased the 156 Franklin Street headquarters building outright and continued to grow the business. As before, the aggressive marketing of Old Crow Whiskey was a principal activity. He also continued Kirk’s strategy of copious advertising, including a patriotic message during World War One.

With the coming of National Prohibition, Spotts was forced to shut the doors on the H. B. Kirk Company. He continued, however, to be embroiled in the liquor trade. In February 1920, a month after the national ban on alcohol took effect, Spotts agreed to sell 480 barrels of Old Crow to a Constantinople, Turkey, dealer named Kyrialddes. Later Spotts discovered that he would not be able to make the shipment and reneged on the oral contract. Kyrialddes sued in a New York court for $51,600 in damages. The case lingered on for months until decided in favor of the Kirk company.

By that time Ralph Spotts, only 48 years old, had died in April 1924, the cause not recorded in obituaries. The location of his burial site similarly does not show up. Josepha would live on another 40 years as his widow, dying and buried in Los Angeles in August 1964 at the age of 90. The gold metal will serve as an epitaph.

Notes: This post was drawn from a wide range of sources. Of particular help were census and business directory references. My prior post on Harford Kirk may be found on this website at March 17, 2022.

.jpg%20-%20C%20.jpg)