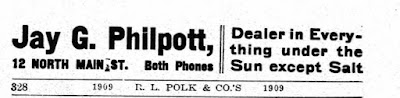

If you chanced to meet Jay George Philpott at one of his Michigan enterprises, he almost certainly would become an instant friend and confidant — and have something to sell. It might be liquor, oysters, insurance, used cars, or even Russian bonds. In one ad Philpott boasted: “Dealer in Everything Under the Sun except Salt.” His home town newspaper termed him a “hale fellow well met” perhaps ignorant that the term often refers to a disingenuous, insincere friendliness. Or maybe not.

If you chanced to meet Jay George Philpott at one of his Michigan enterprises, he almost certainly would become an instant friend and confidant — and have something to sell. It might be liquor, oysters, insurance, used cars, or even Russian bonds. In one ad Philpott boasted: “Dealer in Everything Under the Sun except Salt.” His home town newspaper termed him a “hale fellow well met” perhaps ignorant that the term often refers to a disingenuous, insincere friendliness. Or maybe not.

The eldest of three sons, Philpott was born in Broome County, New York in November 1866, to Alice (Mosher) and Thomas Philpott, a Civil War veteran and iron worker. Indicating that the family was not wealthy, the 1870 census recorded the boy Jay working as a clerk at the age of 14, apparently in a Utica, New York, drug store. In 1885, at age 19, Philpott passed the state exam to become a licensed pharmacist.

The youth eventually was drawn to other locales and occupations, moving to Detroit, Michigan, to work for the Koppitz-Melcher Brewing Company in sales. The brewery was the brain child of Konrad F. Koppitz, an immigrant from Austria who was a highly respected brewmaster when he organized and became company president. From Koppitz Philpott may have learned the value of assertive advertising, e.g. the brewery’s claim to make “Detroit’s Perfect Beer.”

In Port Huron, left, his J.G. Philpott liquor house began by operating in a small space in the downtown McMorran-Davidson Office Building, shown below. By 1910 the organization had expanded to include a mail order business with operations on three floors.

In Port Huron, left, his J.G. Philpott liquor house began by operating in a small space in the downtown McMorran-Davidson Office Building, shown below. By 1910 the organization had expanded to include a mail order business with operations on three floors.

In a “puff” piece in the Port Huron Times-Herald in June, 1910, a reporter described the storefront on the ground floor as being the most elaborately furnished business in the city, likened to a bank with its “heavy counters” and “fancy brass lattice or wicket work.” The writer went on to extoll the main stock room as resembling a drug store with liquor kept in “fancy mahogany and cherry finished cases.” The story continued: “A large number of people are employed in the bottling department, where all kinds of high grade liquors are prepared for shipment. In the labeling department a number of girls find employment.”

Philpott himself was quoted extensively: “No matter how deeply we cut prlce we never cut quality. All the goods we sell are the highest grade in their respective classes. We give the promptest, most careful and most efficient service that an up-to-date, finely equipped and thoroughly trained organization is capable of.”

The reporter felt constrained to point out that the J.G. Philpott Co. had never been accused of breaking the law. Perhaps not, but stretching the truth, Philpott claimed his establishment was the “Largest Wholesale Liquor Store and Mail Order House in Michigan.”

As was customary with liquor enterprises like Philpott’s, it featured two house brands, likely mixed up on premises. They were “Killarney Straight Whiskey” and “King Edward XII Straight Whiskey.” The owner did not bother to register a trademark for either label. As was customary for liquor wholesalers, Philpott issued shot glasses for both brands. They would have been given to customers in saloons, restaurants and hotels for use over the bar.

According to his biography in the 1909 “History of Lewanee County,” Philpott also was a gentleman farmer . On the outskirts of Adrian he bought a 20 acre spread on which he raised poultry. The biographer noted: “He is a great fancier of finely bred chickens, and his pens of Houdans, Brahmas, and Leghorns [shown below in that order] have won many prizes at different fairs and poultry shows where they have been exhibited.

While his businesses and poultry hobby apparently were going well, Philpott’s marital situation was not. In June of 1890 he had married 22-year old Gertrude Durham, the daughter of Joseph Durham of Romeo, Michigan. They wed in Sarnia, Canada, the birth country of Gertrude’s mother’s. There would be no children. The stress on their marriage from the outset seems inevitable. Philpott frequently was absent from their Adrian home for extended periods as he traveled to Port Huron to run his business there. His wife may have been left behind to feed the chickens. After nine years, she called it quits. Charging Philpott with “extreme cruelty” Gertrude obtained a divorce.

Philpott, now 45, married again two years later. This time his bride was Ernestine Bowsky, 26, originally from a New York State family. The couple would have one son. They named him Jay George Philpott II. This time Philpott made Port Huron his home base, housing his family at 517 Rawlins Street in a three story residence boasting a white pillared porch.

Philpott, now 45, married again two years later. This time his bride was Ernestine Bowsky, 26, originally from a New York State family. The couple would have one son. They named him Jay George Philpott II. This time Philpott made Port Huron his home base, housing his family at 517 Rawlins Street in a three story residence boasting a white pillared porch.

Philpott’s economic fortunes were about to change abruptly. With prohibitionist Henry Ford leading the charge, Michigan in 1917 became the first Midwest State to outlaw the making and sales of alcohol. This development apparently led him to shut down his Adrian company and in Port Huron shift to selling groceries. When that enterprise proved unsatisfactory, Philpott moved, as many former whiskey men did, into the newly burgeoning automotive field. He opened a business he called “Auto Sales Co” at 531 Water Street. References to this company in Port Huron directories indicate that Philpott was selling auto insurance. Not identified as a dealer for a specific make, Philpott apparently was selling used cars, a perfect venue for a pitchman.

From the Water Street location, the “hale fellow well met” also was dealing in foreign securities, more specifically, Russian Imperial bonds. These were highly speculative investments. After coming to power the Soviet Government of Russia repudiated honoring any securities issued by the Czarist regime. Given the extraordinary amounts of money involved, European bankers and others desperately kept alive the idea that someday the bonds would be paid off. From time to time they floated rumors from of progress in negotiating with Russia’s Communist government. The stories spiked brief inflation of values. Banks and bond agents cashed in; small investors lost when the rumors proved to be just rumors.

Philpott, always open to opportunity, energetically was peddling Russian bonds to his fellow citizens, promising big returns once things got straighten out in Moscow. By 1929, the Michigan Securities Commission in Lansing had had enough. According to press accounts: “Philpott is said to have disposed of virtually worthless Russian bonds to Michigan investors at a considerable loss to the latter…The Commission is seeking to revoke Philpott’s brokerage license and has ordered him to show cause why this action should not be taken.” Although I cannot find the outcome of this official action, Russian bonds eventually proved to be all but worthless.

In the interim Philpott, the “hale fellow” died, age 58. He succumbed at home on May 27, 1930, after a brief illness. His funeral services were held at the residence, officiated by the Rev. Austin DuPlan, pastor of Grace Episcopal Church. His remains, accompanied by his widow, Ernestine, and their son, were taken by train to Utica, New York. Jay George was buried in the Philpott family plot in nearby Oriskany Cemetery. Ernestine is not buried with him.

In the interim Philpott, the “hale fellow” died, age 58. He succumbed at home on May 27, 1930, after a brief illness. His funeral services were held at the residence, officiated by the Rev. Austin DuPlan, pastor of Grace Episcopal Church. His remains, accompanied by his widow, Ernestine, and their son, were taken by train to Utica, New York. Jay George was buried in the Philpott family plot in nearby Oriskany Cemetery. Ernestine is not buried with him.

Note: This post was constructed from a wide range of sources. The most important was Philpott’s biography in “The History of Lenawee County Michigan,” Vol. I; Editor, Richard I. Bonner; Western Historical Assn., Madison WI, 1909.