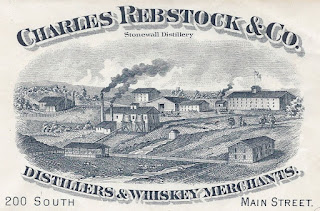

For years I have been collecting the images of trade cards that Charles Rebstock, St. Louis distiller and philanthropist, issued during his lifetime.I first told Rebstock’s story on this website on September 6, 2011, but on a careful perusal of these advertising artifacts, it occurs to me that their themes reflect in additional ways this whiskey man’s personality and life experience. They also indicate the ability of Rebstock, shown here, to combine both artistic and business sense.

For years I have been collecting the images of trade cards that Charles Rebstock, St. Louis distiller and philanthropist, issued during his lifetime.I first told Rebstock’s story on this website on September 6, 2011, but on a careful perusal of these advertising artifacts, it occurs to me that their themes reflect in additional ways this whiskey man’s personality and life experience. They also indicate the ability of Rebstock, shown here, to combine both artistic and business sense.

Many of Rebstock’s trade cards feature the forms and faces of young girls, often interacting with birds, butterflies, or flowers. Never boys. My thought is that these images in emotional ways relate to his wife, Pauline, a St. Louis-born girl only about 20 years old when they married. Charles was ten years older. They had no children. After Pauline died at age 36 in 1893, he never remarried.

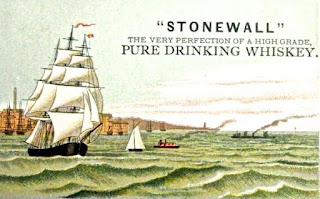

Possibly in an effort to assuage his grief, not long after Pauline’s death, Rebstock took the first of two long “around-the-world” ocean voyages. The trade card here may represent the various type of marine craft that he employed in his extensive travels, including a masted schooner, sailboat, steamboat and lighter.

Rebstock is accounted to have visited Europe, the Middle East, Asia and Africa. When he found a country he particularly liked, he made his stay a prolonged one. From his trade cards, Turkey may have been among them. Two images reflect that interest, one of a horseman in a fez galloping over a landscape and a second entitled “Turkish Ladies Sport.”

Another of Rebstock’s favored countries may well have been Spain. At least two of his trade cards featured bullfight scenes. In one the matador has made a sweep around the bull with his red cape while a picador on horseback prods the doomed animal with his lance. A second card finds the bull slain and being dragged out of the stadium.

Those cards that appear purely decorative may also have a meaning. The one at left of a boater approaching a stone bridge carries the logo of the Cliff House in Deadwood, Dakota Territory. Three others shown here also carry customer names. The towns noted — Perrysville, Missouri, and Fairbault and St. Peter, Minnesota — all are relatively small, indicating that Rebstock was making such communities the objects of his marketing efforts for “Stonewall” whiskey. The reverse of the hand and flowers trade card contains a long verse in celebration of the brand, ending:

A man’s a fool to live in grief,

When he can get complete relief,

And feel as happy as a clam,

Drinking “STONEWALL” by the dram.

Rebstock also was providing individualized calling cards for his traveling salesmen when they visited towns around the Middle West. Each carries the likeness of the “drummer.” At left is Rebstock’s younger brother, Edward; at right, John C. Hochmuth, a longtime company sales representative.

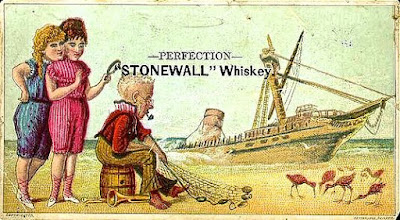

The meaning of the final trade card is puzzling without understanding the back story. It depicts two young women with a magnifying glass examining the head of a man sitting on a shoreline contemplating a beached and presumably wrecked ship. The image may seem less strange upon learning that Rebstock in 1880 commissioned a Mississippi steamboat to be built in St. Louis. Carrying his name, the packet was intended to convey his whiskey to customers along Mississippi and its tributaries. The venture proved unprofitable and three years later Rebstock sold the ship. It later burned and was junked. I surmise that the seated figure represents Rebstock himself, comically having his head examined about his venture into steamboats.