Foreword: For the most part individuals involved in the liquor trade were not an introspective lot. Presented here are exceptions in which three of them provided diary entries or letters that detailed their activities on a regular basis. Each of the “whiskey men” chronicled here were deceased when their writings were rediscovered and believed significant enough for reprinting in book form. This post offers a brief introduction to each.

It is likely that the world would never have heard of Joseph J. Mersman, if Dr. Linda A. Fisher, a public health physician, had not been doing research on the 1849 St. Louis cholera epidemic and came across Mersman’s diary at the Missouri Historical Society where it had laid “undiscovered” for years. She found the whiskey merchant’s story intriguing and eventually edited it with annotations and put it into book form, published in 2007 by the Ohio University Press. As a result the day to day activities and thoughts of the German-born St. Louis liquor dealer and whiskey blender became available for a wider audience.

It is likely that the world would never have heard of Joseph J. Mersman, if Dr. Linda A. Fisher, a public health physician, had not been doing research on the 1849 St. Louis cholera epidemic and came across Mersman’s diary at the Missouri Historical Society where it had laid “undiscovered” for years. She found the whiskey merchant’s story intriguing and eventually edited it with annotations and put it into book form, published in 2007 by the Ohio University Press. As a result the day to day activities and thoughts of the German-born St. Louis liquor dealer and whiskey blender became available for a wider audience.

Mersman, born in Germany and brought to the United States as a child, began working at 15 in the whiskey trade at a successful Cincinnati liquor house. In November 1847 when he was about 23 years old he began his diary, documenting his work in the whiskey house and other aspects of his daily life. Completing his apprenticeship and now free to strike out on his own, Mersman moved to St. Louis, Missouri, and at 25 years of age with a partner established a whiskey and tobacco business.

He also found a wife, Claudine. Their first child, a boy they named Joseph, was born 13 months later. A touching photograph of mother and son is shown here. The couple would go on to have eight children. In his diary Mersman recorded his enjoyment of his growing family, noting that he was becoming “quite domesticated.” In March 1855, Mersman abandoned his diary only to take it up again in 1862 after the outbreak of the Civil War. Despite Missouri being a hotbed of Confederate sentiment and conflict, he thrived. Having signed loyalty oaths to the Union, he and his partner were able to obtain lucrative contracts with the Union Army to provide whiskey for the troops.

He also found a wife, Claudine. Their first child, a boy they named Joseph, was born 13 months later. A touching photograph of mother and son is shown here. The couple would go on to have eight children. In his diary Mersman recorded his enjoyment of his growing family, noting that he was becoming “quite domesticated.” In March 1855, Mersman abandoned his diary only to take it up again in 1862 after the outbreak of the Civil War. Despite Missouri being a hotbed of Confederate sentiment and conflict, he thrived. Having signed loyalty oaths to the Union, he and his partner were able to obtain lucrative contracts with the Union Army to provide whiskey for the troops.

Dr. Fisher sees Mersman’s diary as “a record of a man transforming himself from an impoverished, unschooled newcomer into a successful, skilled merchant…a path many took in the mid-nineteenth century.” All that is true but seen from a slightly different perspective, his story also demonstrates how the liquor trade in particular hastened the economic and social rise of immigrants who understood — as Joseph Mersman clearly did — the weath to be made.

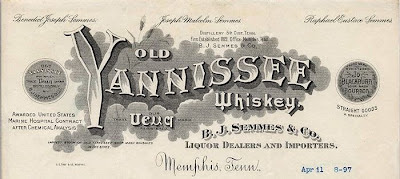

In May 1915, I did a post on Benedict Joseph (B.J.) Semmes, born into a whiskey-making Washington, D.C., family. But it was not until he had wooed and won the love of his life, Jorantha, the daughter of a New York congressman, that with her support Semmes was able to prevail through the crisis of the Civil War and maintain a whiskey dynasty down to three generations. Serving as a supply officer for the Confederate Army, Semmes wrote Jorantha (he called her “Eo,”) every day an account of the 1864 Battle for Atlanta. The letters lay idle at the University of North Carolina for decades until Author A.A. Hoehling unearthed them for his book, “Last Train from Atlanta.” Following are some excerpts:

In May 1915, I did a post on Benedict Joseph (B.J.) Semmes, born into a whiskey-making Washington, D.C., family. But it was not until he had wooed and won the love of his life, Jorantha, the daughter of a New York congressman, that with her support Semmes was able to prevail through the crisis of the Civil War and maintain a whiskey dynasty down to three generations. Serving as a supply officer for the Confederate Army, Semmes wrote Jorantha (he called her “Eo,”) every day an account of the 1864 Battle for Atlanta. The letters lay idle at the University of North Carolina for decades until Author A.A. Hoehling unearthed them for his book, “Last Train from Atlanta.” Following are some excerpts:

July 22: “Our communications have been cut as I foretold you and this is a chance just offered to write you. Before day this morning we evacuated Atlanta but left the Army in line of battle around the city…A terrible battle is raging around the city and in fact in it.

July 25: “The enemy continues the wanton shelling of the city….For 30 hours they shelled my Depot where our stores are issued….Gen. Hood ordered us with the train of cars a little out of the range and now I am writing in a car on the R. Road while the shells are flying over me….I am well during all these troubles and am chiefly troubled since I no longer hear from you….God bless you and pray for me.”

July 28: “I can only say that I am tolerably well, and love you as much as you could wish, and much more than I know how to put on paper…I send a heartfull of love to all my little ones and my relations.”

August 7: “I have been quite unwell and very feeble but today feel much better and stronger in every way, especially since I have been to Mass for the first time since we left Dalton….I felt you were by my side. It was consoling to me at this time especially for I am living in danger hourly and daily.

August 12: “After a sleepless night, [I] cannot refrain from writing to my darling Eo my regular letter. Today my heart is very loving and my very arms yearn to press to my heart the living, breathing form of my beloved wife….I have you constantly in my thoughts, especially in the hour of danger.”

August 12: “After a sleepless night, [I] cannot refrain from writing to my darling Eo my regular letter. Today my heart is very loving and my very arms yearn to press to my heart the living, breathing form of my beloved wife….I have you constantly in my thoughts, especially in the hour of danger.”

August 25: “For the past 48 hours the enemy has shelled us terribly….The day before a young man from Manin, Ala,, dined with us, and two hours after dinner his leg was amputated on the same table we dined from.”

August 30: Semmes was evacuated from Atlanta by train. As supply officer he directed military supplies by rail through a hotly contested area and was able to arrive at a safe location twelve miles north of the city. He told his “beloved wife” to gather the children, fall on her knees and thank God for his “protection” and “preservation from a most horrible death or most shocking wounds.” After the Confederate surrendered Semmes made his way home, rejoined Jorantha and his family, and continued his successful liquor business.

Hand was equally faithful in documenting his visits and payments to Tucson prostitutes: Jan. 13, 1875: “Cruz—$5.00;” Jan. 18, 1875: “Unknown girl—$3.00;” Nov. 6, 1875: “Juana—$1.00.” Dec. 23, 1876: “Called on Pancha a few moments—$10.” Hand also described the raucous activity at the saloon: May 23, 1875: “Green Rusk got tight, had a row with John Luck and got a cut in his head from a cane.” May 29, 1875: “Boyle hit a man in the eye for calling him a son-of-a-bitch. Later in the evening I knocked a man down,” Mar. 9, 1876: “Mr. Bedford, being full of liquor, made a row with old Dick. Foster hit Bedford in the neck and put him out of doors.”

|

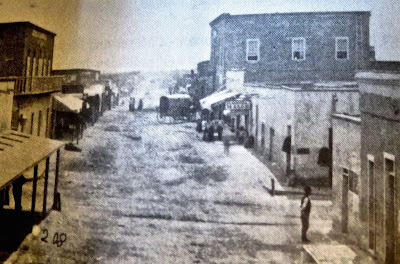

| Man Right Standing at Hand's Saloon |

Interspersed among such diary jottings are some Western history gems: "March 19, 1882: “Morgan Earp died today from a gunshot wound he received while playing billiards in Tombstone. He was shot through a window from the sidewalk.” March 21, 1882: “Frank Stillwell was shot all over, the worst shot-up man that I ever saw. He was found a few hundred yards from the hotel on the railroad tracks [In Tucson]. It is supposed to be the work of Doc Holliday and the Earps, but they were not found. Holliday and the Earps knew that Stillwell shot Morg Earp and they were bound to get him.”

Twenty years after Hand’s death in May 1887, The Arizona Daily Star, Tucson’s morning newspaper, began publishing entries from his diaries as a historical feature on its editorial page. From 1917 to 1972, the saloonkeeper’s observations were printed almost daily, bringing a man who otherwise likely would have been utterly forgotten to the forefront of public attention. As his biographer Neil Carmody has noted: “For more than four decades, thousands of Arizonians began their day reading George Hand’s laconic [and sometimes expurgated] comments on frontier life.”

Twenty years after Hand’s death in May 1887, The Arizona Daily Star, Tucson’s morning newspaper, began publishing entries from his diaries as a historical feature on its editorial page. From 1917 to 1972, the saloonkeeper’s observations were printed almost daily, bringing a man who otherwise likely would have been utterly forgotten to the forefront of public attention. As his biographer Neil Carmody has noted: “For more than four decades, thousands of Arizonians began their day reading George Hand’s laconic [and sometimes expurgated] comments on frontier life.”

Carmony has described the importance of Hand’s “saloon diary:” “Most of the pioneers who took the time to keep a diary were serious and orderly folks, not much given to humor and certainly not frank about their lives and loves.…In his diary, George Hand captured the flavor of the ribald, fun side of frontier life, described the often violent West, and revealed the…loneliness and tedium of a life far from home and family.”

Note: More complete vignettes on each of these “whiskey men” may be found elsewhere on this post: Joseph Mersman, May 26, 2017; B.J. Semmes, May 11, 2015; and George Hand, April 11, 2021.

.jpg-%20R.jpg)