Isaac Weil, one of Minnesota’s leading pre-Prohibition whiskey dealers, spent much of a lifetime linking the Europe of his youth with his new homeland in the United States. In the process he occasioned a host of attractive artifacts advertising his alcoholic beverages.

Weil was born in 1847 and educated in what is now the Czech Republic. At the age of 19 in 1866 he emigrated to the United States. His first stop was a brief one in New York City. Moving to Chicago, he witnessed the great fire of 1871 and found a wife, Hannah Bachrach. It was in Chicago that Isaac and Hannah’s first children were born.

Minnesota beckoned as a new frontier. In 1879 the growing Weil family moved to Minneapolis. Soon after Isaac opened a downtown saloon at 210 Hennepin Avenue. His establishment featured a 50-foot back bar of ornate mirrors and elaborately carved wood. Whiskey sold for five cents a shot and 25 cents a half pint. For another nickel Isaac would give you a bar lunch.

Weil has been described as a large but gentle individual, well-liked by his customers and generous with his money. His abundant hair had turned white by the time he reached 26 and he sported a large bushy white mustache. He is shown above on a medallion struck for his 75th birthday.

Weil has been described as a large but gentle individual, well-liked by his customers and generous with his money. His abundant hair had turned white by the time he reached 26 and he sported a large bushy white mustache. He is shown above on a medallion struck for his 75th birthday.

The saloon proved very popular. The next year Isaac added an outlet for wholesale and retail liquor. In 1887 he christened his business Isaac Weil & Co. At the same time, however, he was constantly revisiting his Old World roots. For many years he went to Europe annually, taking one child along each time.

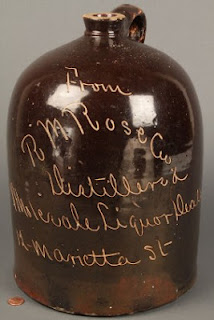

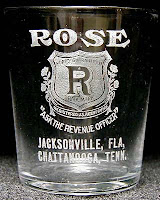

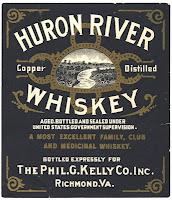

While there, Weil personally chose all the wines, liquors and liqueurs he would import to Minneapolis. He also visited potteries to choose whiskey nips. He admired the Old World craftsmanship with which these items were designed and produced. Among his destinations was the famous Schafer & Vader factory in Thuringen, Germany. From them, for example, he purchased the whimsical standing figure holding a syringe and “Weil” incised in the base. It is estimated that over his lifetime Isaac gave away 40 different small ceramic mini decanters. Among them were tea kettles and small jugs.

Weil enjoyed presenting these gifts to customers, particularly at the Christmas season. On a regular basis he also gave away tokens worth a nickel or dime that could be redeemed in trade at his bar or restaurant. Early on, Weil adopted the slogan, seen on his containers, “Everything Drinkable,” signaling the wide range of beverages to be had in his establishment. Eventually, needing larger premises, he moved to 42-44 South Sixth St. in Minneapolis and later opened a second liquor store at 39-41 South Third St.

In 1905 Isaac took three of his five sons into the business, changing the name to Isaac Weil & Sons. Charles Weil became vice president and treasurer. Benjamin was secretary and Hermann served as a clerk until 1911 when he became a branch manager. The sons were still living at home with their folks in 1905 when their mother, Hannah, died.

In 1905 Isaac took three of his five sons into the business, changing the name to Isaac Weil & Sons. Charles Weil became vice president and treasurer. Benjamin was secretary and Hermann served as a clerk until 1911 when he became a branch manager. The sons were still living at home with their folks in 1905 when their mother, Hannah, died.

Among other Old World traditions Isaac respected was his Jewish heritage. He adhered to the Reformed Hebrew tradition, serving many years as the president of Temple Israel in Minneapolis. He also was one of the founders of the Montefiore Reformed Cemetery there. A grandson has said of him: “Isaac owned a saloon and used the profits to support the synagogue and Jewish Community.”

Through the first two decades of the 1900s Weil continued at the helm of his liquor enterprises, working with his boys until Prohibition. Then his sons all went into other occupations. Isaac himself retired and died in 1925, age 78. He is buried in the Montfiore Cemetery next to Hannah and other family members.

With Repeal in 1934 Hermann Weil revived Isaac Weil & Sons Co., acting as president and treasurer. A younger brother, William, became manager. Located at 28 S. Sixth St., the establishment boasted a tunnel to the Radisson Hotel nearby that bellhops could access to buy liquor for guests even in harsh wintertime conditions. Starting anew amidst the Great Depression, the business survived only four years. In 1938 it disappeared from city directories and William went to work as a salesman for Schenley Distillers Corp.

“And so ended another of Minneapolis’ great liquor establishments,” declared Ron Feldhaus, whose “The Bottles, Brewiana and Advertising Jugs of Minnesota," Vol. II (1987), was the source of much of the information provided here. But this sad outcome does not tarnish the warm memories of Isaac Weil, a man who brought many good things, drinkable and otherwise, from Europe to America.

Note: The Weil ad above with the young girl holding flowers was sent to me in August 2018 by Carol Blood of Isanti, Minnesota, a town about 40 miles north of Minneapolis. Two of these placards are decor in a large piece of furniture, possibly a desk, that Ms. Blood inherited from her mother-in-law. We both believe that the piece likely once stood in Isaac Weil's Minneapolis offices.

While there, Weil personally chose all the wines, liquors and liqueurs he would import to Minneapolis. He also visited potteries to choose whiskey nips. He admired the Old World craftsmanship with which these items were designed and produced. Among his destinations was the famous Schafer & Vader factory in Thuringen, Germany. From them, for example, he purchased the whimsical standing figure holding a syringe and “Weil” incised in the base. It is estimated that over his lifetime Isaac gave away 40 different small ceramic mini decanters. Among them were tea kettles and small jugs.

Weil enjoyed presenting these gifts to customers, particularly at the Christmas season. On a regular basis he also gave away tokens worth a nickel or dime that could be redeemed in trade at his bar or restaurant. Early on, Weil adopted the slogan, seen on his containers, “Everything Drinkable,” signaling the wide range of beverages to be had in his establishment. Eventually, needing larger premises, he moved to 42-44 South Sixth St. in Minneapolis and later opened a second liquor store at 39-41 South Third St.

In 1905 Isaac took three of his five sons into the business, changing the name to Isaac Weil & Sons. Charles Weil became vice president and treasurer. Benjamin was secretary and Hermann served as a clerk until 1911 when he became a branch manager. The sons were still living at home with their folks in 1905 when their mother, Hannah, died.

In 1905 Isaac took three of his five sons into the business, changing the name to Isaac Weil & Sons. Charles Weil became vice president and treasurer. Benjamin was secretary and Hermann served as a clerk until 1911 when he became a branch manager. The sons were still living at home with their folks in 1905 when their mother, Hannah, died.Among other Old World traditions Isaac respected was his Jewish heritage. He adhered to the Reformed Hebrew tradition, serving many years as the president of Temple Israel in Minneapolis. He also was one of the founders of the Montefiore Reformed Cemetery there. A grandson has said of him: “Isaac owned a saloon and used the profits to support the synagogue and Jewish Community.”

Through the first two decades of the 1900s Weil continued at the helm of his liquor enterprises, working with his boys until Prohibition. Then his sons all went into other occupations. Isaac himself retired and died in 1925, age 78. He is buried in the Montfiore Cemetery next to Hannah and other family members.

With Repeal in 1934 Hermann Weil revived Isaac Weil & Sons Co., acting as president and treasurer. A younger brother, William, became manager. Located at 28 S. Sixth St., the establishment boasted a tunnel to the Radisson Hotel nearby that bellhops could access to buy liquor for guests even in harsh wintertime conditions. Starting anew amidst the Great Depression, the business survived only four years. In 1938 it disappeared from city directories and William went to work as a salesman for Schenley Distillers Corp.

“And so ended another of Minneapolis’ great liquor establishments,” declared Ron Feldhaus, whose “The Bottles, Brewiana and Advertising Jugs of Minnesota," Vol. II (1987), was the source of much of the information provided here. But this sad outcome does not tarnish the warm memories of Isaac Weil, a man who brought many good things, drinkable and otherwise, from Europe to America.

Note: The Weil ad above with the young girl holding flowers was sent to me in August 2018 by Carol Blood of Isanti, Minnesota, a town about 40 miles north of Minneapolis. Two of these placards are decor in a large piece of furniture, possibly a desk, that Ms. Blood inherited from her mother-in-law. We both believe that the piece likely once stood in Isaac Weil's Minneapolis offices.