If there were a social and political aristocracy in the United States during 18th and 19th Centuries, the Horsey family of Maryland certainly had to be counted among it. What then could have compelled the scion of the family, a youth with the unlikely given name of Outerbridge, to decide upon turning 19 that the passion of his life would be to make good whiskey?

|

| Needwood Mansion |

Outerbridge Horsey IV was a direct descendant on his mother’s side from Charles Carroll, a Maryland signer of the U.S. Constitution and one of the state’s most famous citizens. His grandfather, Thomas Sim Lee, twice had been governor of Maryland. His father, Outerbridge III, was a U.S. Senator from Delaware and earlier its Attorney General. The blood lines ran blue.

The family also was wealthy. Governor Lee had established a plantation of 2,000 acres in Frederick County, Maryland, in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains, near the present town of Burkittsville. On it he built a mansion he called “Needwood.” The youngest of four children, Outerbridge IV was born on the estate in 1819.

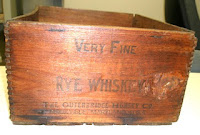

Inheriting land at Needwood at an early age, Outerbridge about 1839 determined not just to farm it, but to establish a distillery. His initial operations appear to have been small with mainly local whiskey sales, in keeping with the Maryland farmer-distiller traditions of that era. Shown below is a Horsey sign at a store in neighboring Boonesboro.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, possibly to avoid military service in the Union Army, Outerbridge IV decamped to Europe for the duration of the fighting. During his absence Needwood became a battleground. On September 13, 1862, Confederate cavalry under General J.E.B. Stuart occupied Burkittsville. Two days later the forces of the Union and Confederate armies clashed at the Battle of Crampton’s Gap, as shown here in an illustration. In the process Horsey’s distillery was destroyed and whiskey he had stored was consumed by thirsty combatants.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, possibly to avoid military service in the Union Army, Outerbridge IV decamped to Europe for the duration of the fighting. During his absence Needwood became a battleground. On September 13, 1862, Confederate cavalry under General J.E.B. Stuart occupied Burkittsville. Two days later the forces of the Union and Confederate armies clashed at the Battle of Crampton’s Gap, as shown here in an illustration. In the process Horsey’s distillery was destroyed and whiskey he had stored was consumed by thirsty combatants.  Despite these setbacks, Horsey remained passionate about making whiskey. He used his sojourn in Europe to visit Scotland and other European distillery sites to learn as much as possible on how to produce high quality liquor. Returning to Maryland after the war, he set about rebuilding his operation and eventually claimed it as “the first Eastern pure rye distillery of the U.S."

Despite these setbacks, Horsey remained passionate about making whiskey. He used his sojourn in Europe to visit Scotland and other European distillery sites to learn as much as possible on how to produce high quality liquor. Returning to Maryland after the war, he set about rebuilding his operation and eventually claimed it as “the first Eastern pure rye distillery of the U.S."  Horsey’s method of aging his whiskey was unusual for the times and brought fame to his operation. Routinely he sent barrels via ship, like the vessel shown here, around Cape Horn to San Francisco and then by railroad back to Maryland for bottling. His theory was that sloshing around inside barrels on the high seas mellowed and aged the whiskey in beneficial ways that sedentary storing in warehouses failed to do. He marked crates containing Horsey Rye with the message: “This whiskey was shipped by sea to San Francisco per S.S. ______, thus acquiring a unique and most agreeable softness.”

Horsey’s method of aging his whiskey was unusual for the times and brought fame to his operation. Routinely he sent barrels via ship, like the vessel shown here, around Cape Horn to San Francisco and then by railroad back to Maryland for bottling. His theory was that sloshing around inside barrels on the high seas mellowed and aged the whiskey in beneficial ways that sedentary storing in warehouses failed to do. He marked crates containing Horsey Rye with the message: “This whiskey was shipped by sea to San Francisco per S.S. ______, thus acquiring a unique and most agreeable softness.”  Horsey marketed his whiskey in bottles with fancy labels, established dealers in nearby towns, and opened an office for his company in Baltimore. Establishments carrying Outerbridge’s brand were given an attractive bar ornament -- a metal horse about four inches high.

With the profits from his whiskey and his farm Outerbridge and his wife, Anna, also a descendent of Charles Carroll, bought a house in Washington, D.C., where the couple spent winters and were active in local high society. Horsey also was the Democratic National Committeeman for Maryland for many years and served on the boards of several major companies.

Horsey marketed his whiskey in bottles with fancy labels, established dealers in nearby towns, and opened an office for his company in Baltimore. Establishments carrying Outerbridge’s brand were given an attractive bar ornament -- a metal horse about four inches high.

With the profits from his whiskey and his farm Outerbridge and his wife, Anna, also a descendent of Charles Carroll, bought a house in Washington, D.C., where the couple spent winters and were active in local high society. Horsey also was the Democratic National Committeeman for Maryland for many years and served on the boards of several major companies. With a daily capacity less of than 400 bushels of mash, production from Horsey’s distillery put it almost squarely in the middle of Maryland’s whiskey makers. Taxable revenues from the operation stayed steady at around $25,000 for many years. During his 60 years in distilling, Horsey steadfastly emphasized maintaining quality over increasing quantities of his whiskey.

At the advanced age of 83 Outerbridge died in 1902. He apparently never disclosed why an heir “to the manor born” would be so passionate about making good whiskey. His obituary in the New York Times emphasized his political connections, adding as an afterthought that he also was a distiller.

Horsey’s aristocratic family apparently had no interest in making whiskey and not long after his death they sold the distillery.

Under new management production doubled by 1907. The name of the whiskey was changed to “Old Horsey.” It was marketed vigorously to a wide drinking audience and quality dropped. An etched shot glass exists from this period.

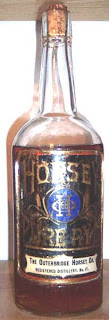

With the advent of Prohibition, operations came to a screeching halt. Upon Repeal in 1934 Sherwood Distilling bought the Horsey distillery and shut it down but kept the well recognized brand name, as shown on a bottle here.

Under new management production doubled by 1907. The name of the whiskey was changed to “Old Horsey.” It was marketed vigorously to a wide drinking audience and quality dropped. An etched shot glass exists from this period.

With the advent of Prohibition, operations came to a screeching halt. Upon Repeal in 1934 Sherwood Distilling bought the Horsey distillery and shut it down but kept the well recognized brand name, as shown on a bottle here.