Foreword: Pennsylvania anthracite coal is known the world over for its clean burning qualities. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density. Some whiskey men began their careers working in the mines of the Keystone State. Others turned their revenues from selling liquor into investments in Pennsylvania coal. This post briefly recounts the story of three such men: one who climbed out of Pennsylvania mining and two who bought into it.

The function of a “breaker boy” in mining was to break coal into pieces and sort those pieces into categories of nearly uniform size, a process known as “breaking." He also chipped away any impurities that might be clinging to the coal. It was hard, low-paying labor. Michael Bosak went from breaker boy in a Pennsylvania mine to proclaiming himself “The Richest Slovak in America”

The function of a “breaker boy” in mining was to break coal into pieces and sort those pieces into categories of nearly uniform size, a process known as “breaking." He also chipped away any impurities that might be clinging to the coal. It was hard, low-paying labor. Michael Bosak went from breaker boy in a Pennsylvania mine to proclaiming himself “The Richest Slovak in America”

Bosak emigrated to the United States from Slovakia at the age of 17. He settled in the anthracite-rich region of Northeastern Pennsylvania and went to work in a mine at Hazelton as a breaker boy to make a living. A photo left shows them at work. Finding the work unrewarding on many counts, he eventually shifted employment and worked for Slovak liquor merchants in the area, taking orders and delivering merchandise. Frugal in his habits, Bosak saved sufficient money to open his own liquor store in Hazelton in the 1890s. When it succeeded he opened a saloon and subsequently a liquor store in Scranton that became his headquarters. By dint of intelligence and hard work he prospered.

Bosak emigrated to the United States from Slovakia at the age of 17. He settled in the anthracite-rich region of Northeastern Pennsylvania and went to work in a mine at Hazelton as a breaker boy to make a living. A photo left shows them at work. Finding the work unrewarding on many counts, he eventually shifted employment and worked for Slovak liquor merchants in the area, taking orders and delivering merchandise. Frugal in his habits, Bosak saved sufficient money to open his own liquor store in Hazelton in the 1890s. When it succeeded he opened a saloon and subsequently a liquor store in Scranton that became his headquarters. By dint of intelligence and hard work he prospered.

Bosak’s wealth allowed him to pursue other business interests. Early on he moved into banking. The force of his personality led other Slovak immigrants to trust him and seek his help in purchasing steamship tickets, exchanging foreign currency, and making small loans. Bosak established a private Scranton bank in 1897 that by 1915 grew into the Bosak State Bank. He organized financial institutions in Northeastern Pennsylvania and became president of the Miners Savings Bank of Olyphant and the Pennsylvania Bank and Trust Company of Wilkes-Barre. Bosak’s operations reaped such a financial bonanza that he proclaimed himsel the "Richest Slovak in America.”

Bosak’s wealth allowed him to pursue other business interests. Early on he moved into banking. The force of his personality led other Slovak immigrants to trust him and seek his help in purchasing steamship tickets, exchanging foreign currency, and making small loans. Bosak established a private Scranton bank in 1897 that by 1915 grew into the Bosak State Bank. He organized financial institutions in Northeastern Pennsylvania and became president of the Miners Savings Bank of Olyphant and the Pennsylvania Bank and Trust Company of Wilkes-Barre. Bosak’s operations reaped such a financial bonanza that he proclaimed himsel the "Richest Slovak in America.”

Bosak’s fall was just as dramatic his rise. Not long after the imposition of National Prohibition shut down his liquor business entirely. The ultimate blow to Bosak’s business empire came in 1929 and the dawn of the Great Depression. His banks faltered and finally in 1931, failed and closed. His earning of a lifetime were virtually wiped out. Bosak was 61 years old. He would live another six years, dying on February 18, 1937.

For several years before the Civil War Samuel “Sam” Dillinger drove a large Conestoga wagon pulled by six horses across the Allegheny Mountains on the Nation Pike, transporting merchandise between Baltimore and Pittsburgh. After settling down in Pennsylvania, he became the second largest distiller in the state, producing fifty newly-filled whiskey barrels every day from his distillery to store in his warehouses and then delivering a quality aged rye to his customers.

For several years before the Civil War Samuel “Sam” Dillinger drove a large Conestoga wagon pulled by six horses across the Allegheny Mountains on the Nation Pike, transporting merchandise between Baltimore and Pittsburgh. After settling down in Pennsylvania, he became the second largest distiller in the state, producing fifty newly-filled whiskey barrels every day from his distillery to store in his warehouses and then delivering a quality aged rye to his customers.

After his first distillery was destroyed by fire in 1881, Dillinger, now with sons Daniel and Samuel Jr. to assist, built a second in Ruff’s Dale, Pennsylvania. This distillery eventually had a mashing capacity of five hundred bushels of grain daily, producing 50 barrels of whiskey, and six warehouses with a combined storage capacity of 55,000 barrels.

Meanwhile, Sam had been expanding further. With growing prosperity he purchased additional farmland adjoining Home Farm until he owned more than 600 contiguous acres, all of it on top of rich fields of coke coal. That spurred him in 1872 to erect a number of coke ovens, eventually said to total more than 100. One author has opined: “Dillinger and Sons are therefore entitled to rank among the pioneer coke producers of Pennsylvania.” Sam also was one of the founders of the Southwest Pennsylvania Railway in 1872 and served as a director for years.

Meanwhile, Sam had been expanding further. With growing prosperity he purchased additional farmland adjoining Home Farm until he owned more than 600 contiguous acres, all of it on top of rich fields of coke coal. That spurred him in 1872 to erect a number of coke ovens, eventually said to total more than 100. One author has opined: “Dillinger and Sons are therefore entitled to rank among the pioneer coke producers of Pennsylvania.” Sam also was one of the founders of the Southwest Pennsylvania Railway in 1872 and served as a director for years.

Marked by extraordinary vigor throughout his life, at age 79 Dillinger in 1889 very suddenly was felled by a paralyzing stroke and never regained consciousness. Interred in the Mennonite Cemetery at Alverton, Dillinger lies beneath a monument, inscribed “Erected to the Memories of an Honest Man and Constant Friend.”

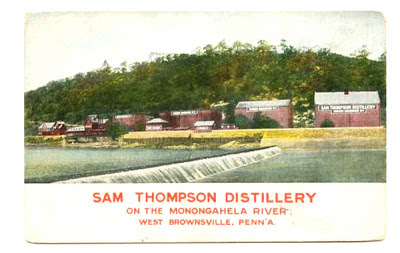

Samuel J. ”Sam” Thompson won a distillery located near Brownsville, Pennsylvania, game in a poker game about 1850 and built it into a going concern. He began with a small plant with the meager capacity of consuming only eight bushels of grain a day but in time enlarged it into the facility shown here in a postcard view. Incorporated into the complex was an old stone building that had been a roadside tavern. It was turned into offices and a small warehouse. During the next several decades, the name Sam Thompson Pure Rye became synonymous with quality whiskey.

Meanwhile Thompson’s ability as a businessman was being recognized. His distillery was the major industry in Brownsville. At the same time, he was moving into other endeavors, hiring a manager to run the distillery and later selling it. Sam invested heavily in the coal business. By 1898 he owned the Champion, Caledonian and Wood's Run Coal Works that had a combined daily output of ten thousand bushels of coal. Those three works were situated close together in Washington County and produced, according to a contemporary account, “ a desirable article of coal which is in great demand in the Western and Southern markets.” Thompson also owned seventeen farms, aggregating three thousand acres of good farming land. All were said to be underlain with coal.

Meanwhile Thompson’s ability as a businessman was being recognized. His distillery was the major industry in Brownsville. At the same time, he was moving into other endeavors, hiring a manager to run the distillery and later selling it. Sam invested heavily in the coal business. By 1898 he owned the Champion, Caledonian and Wood's Run Coal Works that had a combined daily output of ten thousand bushels of coal. Those three works were situated close together in Washington County and produced, according to a contemporary account, “ a desirable article of coal which is in great demand in the Western and Southern markets.” Thompson also owned seventeen farms, aggregating three thousand acres of good farming land. All were said to be underlain with coal.

Sam died in December 1899 at the age of 79 and was buried in a Thompson family plot in the Beallsville Cemetery, Washington County, Pennsylvania. After 1920 the distillery he built was shut forever and left to molder for decades along the banks of the Monongahela River. Sam’s whiskey is still celebrated as one of the finest ryes ever produced in Pennsylvania.

Note: Longer posts on each of these whiskey men can be found on this blog: Michael Bosak, August 23, 2013; Sam Dillinger, February 12, 2016; and Sam Thompson, September 4, 2012. An earlier piece on whiskey men and mining appeared on August 25, 2020.