After earning an education from the prestigious University of Michigan Medical School, Dr. Charles Storm Hazeltine upon moving to Grand Rapids, Michigan, abandoned his practice in favor of operating a wholesale drug business with a full line of liquor as well as highly alcoholic remedies of his own concoction. If you had stomach problems or difficulties urinating, Dr. Hazeltine, shown here, had just the right answer.

After earning an education from the prestigious University of Michigan Medical School, Dr. Charles Storm Hazeltine upon moving to Grand Rapids, Michigan, abandoned his practice in favor of operating a wholesale drug business with a full line of liquor as well as highly alcoholic remedies of his own concoction. If you had stomach problems or difficulties urinating, Dr. Hazeltine, shown here, had just the right answer.

For example, his “Fluid Extract Rhubarb” show below, was recommended as a “Laxative, purgative, stomachic…and corrective in diarrhea.” The dose indicated was 1 to 2 “fluidrachims,” an archaic term for fluid ounces. One had only to turn to the front of the medicinal bottle to discover that this rhubarb packed a punch. It was 50 percent alcohol. Measured as “proof” in liquor, it was 100 proof, higher than most whiskey (80), vodka (80), gin (80) and brandy (70 to 120).

Shown below is Hazeltine’s “Fluid Extract Dwarf Elder” (e.g., sassafras). This remedy was touted as a diuretic “much employed in dropsy, suppression of urine, and other urinary diseases.” The dose was the same as for rhubarb extract but the alcoholic content was 40 percent or 80 proof. Of what use this woody extract might be against “dropsy,” a severe heart condition, went unexplained.

In addition, Dr. Hazeltine offered “A full line of whiskey, brandies, gins, wines, rums.” Moreover the drug company claimed to be “…Sole agents in Michigan for W.D. & Co. [Withers, Dade] Henderson County Hand made Sour Mash Whiskey and Druggists’ Favorite Rye Whiskey.” Moreover the doctor had his own proprietary liquor brands, among them, “Canada 1890 Finest Malt Whiskey” and “Canmalt Finest Blended Whiskey.”

In addition, Dr. Hazeltine offered “A full line of whiskey, brandies, gins, wines, rums.” Moreover the drug company claimed to be “…Sole agents in Michigan for W.D. & Co. [Withers, Dade] Henderson County Hand made Sour Mash Whiskey and Druggists’ Favorite Rye Whiskey.” Moreover the doctor had his own proprietary liquor brands, among them, “Canada 1890 Finest Malt Whiskey” and “Canmalt Finest Blended Whiskey.”

The journey of Dr. Hazelton from the medical profession to huckstering alcohol began in Jamestown, New York, where he was born in October 1844. His parents were Caroline Boss and Dr. Gilbert W. Hazeltine, an eminent East Coast physician and surgeon, who taught anatomy in Philadelphia and New York medical schools. As the eldest of four children, perhaps it was pre-ordained that Charles would be a doctor.

With his father affluent enough to give Charles excellent schooling opportunities, he was educated at the Jamestown Academy, founded by a Hazeltine relative. From there he entered the medical school at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. From the beginning this institution was known as a leader in cutting edge medical education, with emphasis on basic clinical research and patient care. After a subsequent internship at an Albany, New York, hospital, Hazeltine returned to Jamestown and conducted a medical practice for 18 months.

Despite his family pedigree, the life of a doctor seems to have held little interest for Hazeltine. He jettisoned the profession and opened a retail drug business in Jamestown. A biographer chronicled: “…But his native town proved to be too limited a field for a person of the doctor’s ambition and he sought the advantages afforded by the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan.” Why Grand Rapids? The city is 132 miles from Ann Arbor, but it is possible Hazeltine may have visited there as a med student. A national center for furniture manufacturing, Grand Rapids was one of the fastest growing cities in America. With a population of only 2,600 in 1850, by 1900 it boasted 87,500 residents. About 1872 the doctor moved there.

By this time the Hazeltine was married to Ella Burwell of Jamestown and the couple had two children. How his wife reacted to the move 445 miles west has gone unrecorded. Hazeltine initially had a difficult time establishing himself in the new environment and went to work for a local hardware and saddle store. Not long after arriving in Grand Rapids, Ella, only 25 years old, died, leaving him with their young children. Two years later Hazeltine married again. This time his wife was Anna Fox, the daughter of a wealthy Massachusetts manufacturer. Charles and Anna would go on to have two children of their own.

The marriage may have opened up a new financial avenue Hazeltine. That same year, with a partner, Charles N. Shepard, he achieved sufficient resources to open a wholesale drug company. The business was recorded as “prosperous from the start.” Shepard had been the first Grand Rapids druggist to feature cure-all “medicines” of his own concoction. Chief among them was Shepard’s Compound Wahoo Bitters, touted as “A Universal Tonic for Everybody.” It was highly alcoholic and set the direction of the new drug enterprise.

The marriage may have opened up a new financial avenue Hazeltine. That same year, with a partner, Charles N. Shepard, he achieved sufficient resources to open a wholesale drug company. The business was recorded as “prosperous from the start.” Shepard had been the first Grand Rapids druggist to feature cure-all “medicines” of his own concoction. Chief among them was Shepard’s Compound Wahoo Bitters, touted as “A Universal Tonic for Everybody.” It was highly alcoholic and set the direction of the new drug enterprise.

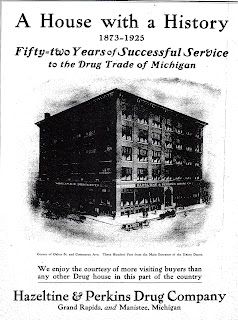

When Shepard died, Hazeltine reorganized the business as a stock company, capitalizing it at $150,000, and, with a partner named Perkins, became its president. From that position he built the Hazeltine, Perkins Drug Company into “the most extensive concern in its line in Michigan,” selling his products in Detroit and other Midwest population centers.

Dr. Hazeltine’s success was noted as far away as the Nation’s Capital. Active in the Democratic Party and supporting the gold standard, he caught the attention of the similarly inclined Cleveland Administration and in 1893 was appointed U.S. consul in Milan, Italy. As U.S. Consul Hazeltine was popular with Americans and Italians for hosting dances in the consulate’s third floor ball room. Although the doctor had agreed to serve only a year, he was induced by the State Department to serve a second term.

Dr. Hazeltine’s success was noted as far away as the Nation’s Capital. Active in the Democratic Party and supporting the gold standard, he caught the attention of the similarly inclined Cleveland Administration and in 1893 was appointed U.S. consul in Milan, Italy. As U.S. Consul Hazeltine was popular with Americans and Italians for hosting dances in the consulate’s third floor ball room. Although the doctor had agreed to serve only a year, he was induced by the State Department to serve a second term.

Returning to Grand Rapids, Dr. Hazelton resumed his roles as president of the drug company and vice president of the Grand Rapids National Bank. In addition, he was on the Board of Trustees of Butterworth Hospital where his efforts were hailed as instrumental in the development of that medical institution. Hazeltine also served as a trustee of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church and was active in the Masons and Grand Rapids social and literary clubs.

Returning to Grand Rapids, Dr. Hazelton resumed his roles as president of the drug company and vice president of the Grand Rapids National Bank. In addition, he was on the Board of Trustees of Butterworth Hospital where his efforts were hailed as instrumental in the development of that medical institution. Hazeltine also served as a trustee of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church and was active in the Masons and Grand Rapids social and literary clubs.

His wealth allowed Dr. Hazeltine to own successively two of the most attractive homes in Grand Rapids. Seen below left is his house on Heritage Hill and right, the final family residence on St. John Hill. Both structures have considerable architectural interest.

As he aged, Dr. Hazeltine continued to manage the giant drug wholesale house. The 1910 Census found him living with wife Anna, a 23-year old daughter, and two female live-in servants. At 65 his health was already beginning to falter. He developed gastric ulcers and a kidney condition known as nephritis. After three years under a doctor’s care, Charles Hazeltine died on December 17, 1912, at the age of 68. He was buried in the Oak Hill Cemetery of Grand Rapids. The family monument is shown here.

As he aged, Dr. Hazeltine continued to manage the giant drug wholesale house. The 1910 Census found him living with wife Anna, a 23-year old daughter, and two female live-in servants. At 65 his health was already beginning to falter. He developed gastric ulcers and a kidney condition known as nephritis. After three years under a doctor’s care, Charles Hazeltine died on December 17, 1912, at the age of 68. He was buried in the Oak Hill Cemetery of Grand Rapids. The family monument is shown here.

The wholesale drug company that Dr. Hazeltine had created and nurtured into Michigan’s largest continued in operation into the 1920s. With liquor distilling and sales cut off by National Prohibition, remedies high in alcohol such as those the doctor created became ever more in demand. They treated to general satisfaction the sharp increase in digestive and other issues that apparently plagued an alcohol-starved America. With whiskey unavailable, rhubarb fluid extract would suffice.

Note: This post was drawn from multiple sources, the most important of which was “Cyclopedia of Michigan, Historical and Biographical, General History of the State and Biographical Sketches of Men, Who Have in their Various Spheres contributed toward its Development,” by John Bersey, Western Publishing Co., 1903.