At the end of the 19th Century when the Wiley Brothers, Harry and Ernest, entered the liquor trade, Kansas City, Missouri, already had dozens of similar houses selling whiskey. How could they distinguish their business from this existing horde? The Wileys decided that one strategy was to feature a hard-drinking raven known as “Fritz Spindle-Shanks” as a focus of their advertising. They may have been unaware that they were tapping into the imagination of an artist, poet and author living far across the Atlantic Ocean in Germany.

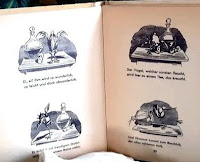

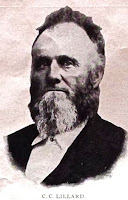

He was Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908) who became famous for his picture stories executed through black and white wood and zinc engravings, many with short rhymed texts of his authorship. Shown here, Busch is still widely known in Germany, especially for his children's stories. Among them was “Hans Hucklebein,” below, where an out-of-control black bird first made an appearance.

He was Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908) who became famous for his picture stories executed through black and white wood and zinc engravings, many with short rhymed texts of his authorship. Shown here, Busch is still widely known in Germany, especially for his children's stories. Among them was “Hans Hucklebein,” below, where an out-of-control black bird first made an appearance.

Not long after its publication a printing firm saw the possibilities of rendering Busch’s creations in color, translating his verses into English, and producing a series of trade cards chronicling the rise and fall of Fritz. They were offered for sale via a catalog to wholesale and retail enterprises. The series proved popular, purchased by companies all over America, among them the Wiley Brothers. My assumption is that Harry and Ernest gave away one or more of these cards with each liquor purchase. The objective was for customers to complete the series, as displayed here:

1. Fritz Spindle-shanks The Raven Black, takes kindly to the applejack.

2. Its taste is sweet, he thrusts his beak, into the liquor stiff and sleek.

3. He takes a nip and with delight, it gurgles slowly out of sight.

4. Immerse his beak again goes back, into the glass of applejack.

5. The glass is raised, his spirit pains, to think that nothing more remains.

6. Whew! Whew! He feels so very queer, with silly look and slinking leer.

7. And screams with wild delight possessed, thus on three toes he blandly rests.

8. But wantoness too often tends, to show the moral of such ends.

9. Thus roughly yanks with vulgar haste, these articles of female taste.

10. He takes a flop and spindle shanks, will ne’re again renew his pranks.

Opened for business in 1887, Wiley Brothers moved frequently during its relatively short years in business, perhaps each time trying to tap into a larger customer base. Their first location was 1002 Main Street, the address referenced on the Fritz series. After two years, they moved to 220 West Fifth St. Just two years later they moved again to 110-112 West Fifth. Their marketing efforts continued to emphasize trade cards, epitomized by the portrait of a fetching little girl. The Wiley’s also went upscale on their whiskey containers. Below are two views of jugs that contained their blends. These ceramics originated in Red Wing, Minnesota, some 350 miles north of Kansas City, and today are much prized by collectors.

Opened for business in 1887, Wiley Brothers moved frequently during its relatively short years in business, perhaps each time trying to tap into a larger customer base. Their first location was 1002 Main Street, the address referenced on the Fritz series. After two years, they moved to 220 West Fifth St. Just two years later they moved again to 110-112 West Fifth. Their marketing efforts continued to emphasize trade cards, epitomized by the portrait of a fetching little girl. The Wiley’s also went upscale on their whiskey containers. Below are two views of jugs that contained their blends. These ceramics originated in Red Wing, Minnesota, some 350 miles north of Kansas City, and today are much prized by collectors.

Apparently neither trade cards nor attractive jugs could sustain Wiley Brothers against intense Kansas City competition. The last business directory entry for the company was 1895. Wiley Brothers whiskey house had lasted just nine years. Unfortunately I have been unable to obtain much personal information about Harry and Ernest. They may have bachelors. The brothers were recorded in 1891 as living together at 1324 Jefferson Street, now an address of a modern apartment building. I am hopeful that a relative will see this post and help fill in personal details.

Note: This post was made possible by the help of Dave Cheadle, a longtime colleague known widely as “The Trade Card Guy.” Dave provided me with information and Internet sources that made possible this post after I had stumbled on the Wilhelm Busch-inspired series of cards. In addition to Dave’s lively commerce in trade cards via the Internet, he maintains a retail presence in the historic Main Street District of Central City, Colorado. The Dave Cheadle window booth and his “Central City Card Bar” inside the store contains exhibits and display for thousands of Victorian trade cards.

Note: This post was made possible by the help of Dave Cheadle, a longtime colleague known widely as “The Trade Card Guy.” Dave provided me with information and Internet sources that made possible this post after I had stumbled on the Wilhelm Busch-inspired series of cards. In addition to Dave’s lively commerce in trade cards via the Internet, he maintains a retail presence in the historic Main Street District of Central City, Colorado. The Dave Cheadle window booth and his “Central City Card Bar” inside the store contains exhibits and display for thousands of Victorian trade cards.