Once upon a time during National Prohibition a family from Atlantic City succeeded in building eighty giant wine bottles across America, two of them shown here. They were the D’Agostinos, father, mother, and son, whose successful ventures into liquor, wine and tonics is remembered best by those huge concrete and plaster monuments, hailed by some as “architectural treasures,” with four bottles in New Jersey protected as historic landmarks.

Once upon a time during National Prohibition a family from Atlantic City succeeded in building eighty giant wine bottles across America, two of them shown here. They were the D’Agostinos, father, mother, and son, whose successful ventures into liquor, wine and tonics is remembered best by those huge concrete and plaster monuments, hailed by some as “architectural treasures,” with four bottles in New Jersey protected as historic landmarks.  The progenitor of this American “Stonehenge” was Matteo D’Agostino. Shown right, he was born in the Messina Province of the Island of Sicily, Italy, in 1871, into the family of Andrea D’Agostino. At the age of 15 in 1886, Matteo emigrated to the United States settling in the vicinity of Atlantic City where he likely had relatives. Five years later his future wife, Maria, came to this country. Born the same year in Messina, she likely had known Matteo in the Old Country. They married in 1992, the same year Matteo became a naturalized citizen. Over the next fourteen years the couple would have seven children. Four of them appeared to have died in infancy or when very young. Their second-born in 1895 was John Andrew, the son who one day would help spread D’Agostino bottles from coast to coast.

The progenitor of this American “Stonehenge” was Matteo D’Agostino. Shown right, he was born in the Messina Province of the Island of Sicily, Italy, in 1871, into the family of Andrea D’Agostino. At the age of 15 in 1886, Matteo emigrated to the United States settling in the vicinity of Atlantic City where he likely had relatives. Five years later his future wife, Maria, came to this country. Born the same year in Messina, she likely had known Matteo in the Old Country. They married in 1992, the same year Matteo became a naturalized citizen. Over the next fourteen years the couple would have seven children. Four of them appeared to have died in infancy or when very young. Their second-born in 1895 was John Andrew, the son who one day would help spread D’Agostino bottles from coast to coast.

Matteo first appeared in local business directories in 1904 as the proprietor of the D’Agostino Hotel at 2230 Arctic Avenue in Atlantic City, an address that shortly after also became the headquarters of D’Agostino’s Wines and Liquors. The Sicilian immigrant had selected an excellent location for both a hostelry and alcohol sales. Atlantic City, the boardwalk shown above, was at the pinnacle of its popularity as a tourist town, attractive for its ocean beach, its gambling, and its reputation for being “wide open” for all kinds of activities. both licit and not so.

D’Agostino appears to have featured only a single proprietary brand of whiskey, one he called “Atlantic County Club.” He never bothered to trademark the label, but issued both a standard shot glass and a tonic shaped glass, shown left, advertising the brand.

D’Agostino appears to have featured only a single proprietary brand of whiskey, one he called “Atlantic County Club.” He never bothered to trademark the label, but issued both a standard shot glass and a tonic shaped glass, shown left, advertising the brand.  He also marketed a spiritous tonic called “Ferro-China Bisleri,” a reputed health giving beverage that had originated in Italy. Its slogan translated from the Italian was “You want good health? Drink Ferro-China Bisleri.” This hype did not impress Food and Drug officials when in 1914 they seized 24 bottles of D’Agostino’s Bisleri bitters in New Jersey and condemned them. The government claimed that they had been spiked with wood alcohol, a poison that can cause blindness and sometimes death. The spiking appears to have been done by the Philadelphia supplier — not the D’Agostinos.

He also marketed a spiritous tonic called “Ferro-China Bisleri,” a reputed health giving beverage that had originated in Italy. Its slogan translated from the Italian was “You want good health? Drink Ferro-China Bisleri.” This hype did not impress Food and Drug officials when in 1914 they seized 24 bottles of D’Agostino’s Bisleri bitters in New Jersey and condemned them. The government claimed that they had been spiked with wood alcohol, a poison that can cause blindness and sometimes death. The spiking appears to have been done by the Philadelphia supplier — not the D’Agostinos. In time John D’Agostino had joined his father in the liquor trade. The son proved to be an even more astute businessman than his father, particularly in the way of cultivating important friends, reputedly including Mafia figures. His most important connection was to Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, the Atlantic City political figure and racketeer. From 1914 to 1941 Johnson was the undisputed “boss” of the Republican political machine that controlled Atlantic City and its government.

In time John D’Agostino had joined his father in the liquor trade. The son proved to be an even more astute businessman than his father, particularly in the way of cultivating important friends, reputedly including Mafia figures. His most important connection was to Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, the Atlantic City political figure and racketeer. From 1914 to 1941 Johnson was the undisputed “boss” of the Republican political machine that controlled Atlantic City and its government.

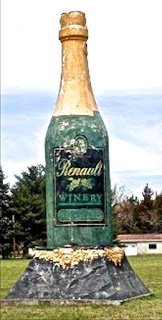

It was likely with Johnson’s help — and almost certainly his approval — that the D’Agostinos with John in the forefront bought the Renault Winery in Atlantic City in 1919. The winery dated from 1864, founded by Louis Renault who found the climate and soils around Atlantic City similar to his native France. Under his tutelage, the winery won prizes for its wine and became the largest distributor of champagne in the U.S.

When the D’Agostinos took over the winery National Prohibition was immanent, a prospect that did not daunt the family. Exploiting a loophole in the laws and with undoubted political influence, they were able to get a government permit to operate throughout the fourteen “dry” years, allowed to produce wines for “religious and medicinal” purposes. Renault Wine Tonic at 40 proof became their chief product and was sold in drug stores nationwide. All one needed was a doctor’s prescription. The label “warned” not to chill the tonic as it would turn into wine.

The winery purchase took John D’Agostino on several business trips to France, one of them to the little village where Louis Renault was born. In the town square where it had stood for 100 years was a giant concrete champagne bottle. It gave John an idea: Why not replicate such a bottle in the United States? Not just in Atlantic City but 80 such bottles, advertising Renault from sea to shining sea. For the job, he reached back to Italy and an artisan named Luigi Portaluppi.

Assisted by his son, Portaluppi began to work his way across America building giant concrete bottles as he went. He would fashion a hollow base of chicken wire or mesh and cover it with a mixture of Portland cement, stone, sand and water. The outside was plastered and painted with the Renault logo. By the end of the 1930s, when champagne and other wine once again were legal, the Italian immigrant had reached Fresno, California, built the 80th bottle — and stopped.

Although these totems proved to be an attention getting way of advertising, they also created problems for the D’Agostinos. When they contracted for the space with landowners, those individuals were expected to maintain the bottles, including paint when needed. If, as inevitably happened, some giants were allowed to go into disrepair, the family ceased to pay any compensation. Angry landowners were known to cover the advertising with plastic or even paint them over.

Although these totems proved to be an attention getting way of advertising, they also created problems for the D’Agostinos. When they contracted for the space with landowners, those individuals were expected to maintain the bottles, including paint when needed. If, as inevitably happened, some giants were allowed to go into disrepair, the family ceased to pay any compensation. Angry landowners were known to cover the advertising with plastic or even paint them over.

Nevertheless, the Renault Winery continued to thrive. Meanwhile "Nucky"Johnson had been fined and sent to jail for tax evasion. He was paroled after four years but his power in Atlantic City was at an end. Indicating just how much the D’Agostinos owned Johnson, he and his young, former model wife were both hired to work for Renault, "Nucky" as a salesman. The winery itself had become a major New Jersey tourist attraction, bringing thousands of visitors annually to the state. Prosperity allowed the D’Agostinos to move to a large home on Atlantic City’s Bartram Street. The house, shown here, was second from the beach.

Matteo and Maria, who had seen several children die young, suffered a even greater blow in 1948 when John D’Agostino was killed in an auto accident in Atlantic City. A local newspaper reported: “It was one of the largest funeral corteges ever seen in the County and was attended by people in all walks of life. The pallbearers were a group of leading businessmen and politicians of Atlantic City with many high in the political and business life of the County acting as honorary pallbearers.” After a funeral Mass at a local Catholic Church, as his aged parents looked on, John was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery of Atlantic County.

While Matteo was recorded as running a hotel in Atlantic City in the 1950 U.S. Census, his wife, Maria, is reputed to have taken the reins of management for the winery after John’s death. Shown here, she would live until 1972, dying at the age of 101. Her husband had preceded her in death, passing away in 1956, age 85. The couple lie under a granite headstone that also covers the children they lost early, as well as John Andrew.

While Matteo was recorded as running a hotel in Atlantic City in the 1950 U.S. Census, his wife, Maria, is reputed to have taken the reins of management for the winery after John’s death. Shown here, she would live until 1972, dying at the age of 101. Her husband had preceded her in death, passing away in 1956, age 85. The couple lie under a granite headstone that also covers the children they lost early, as well as John Andrew.

Since the passing of the D’Agostinos’ the giant Renault bottles have taken on an iconic status. The State of New Jersey has declared the four that remain there to be protected historic landmarks. D’Agostino’s bottles continue to stand in other parts of America, including Fresno, although the Atlantic City winery long since has been in other hands.

Dr. Cecil Munsey, a now-deceased guru of the bottle collecting community, has declared them architectural treasures. "Unfortunately, I don't think we'll ever go back to having giant champagne bottles or this kind of thing in general because cities no longer allow for such things in the building codes," Munsey has said, adding: "We are left to be fascinated with the examples we still have.”

To those sentiments I would just note that these giant sculptures also remind us of the D’Agostinos whose hard work, foresight and — yes, political pull — made these memorable objects possible.