The saloon token above, good for a princely $1.00 in trade, has no identification as to who issued it, on both sides simply stating “Whoop-E-Tee-Whoop” and Durango. It had no need to. Everyone in Durango knew this was the standard greeting and trademark of John Kellenberger, a Swiss immigrant who came to the Colorado town run a liquor business and saloon and became a local legend for his colorful personality.

Kellenberger, shown here about 1901, was born in 1861 and came to the United States in 1880. After landing in New York City, the young Swiss made his way to Brechenridge, Colorado, perhaps drawn there by the similarities in the landscape of his homeland that promised Alpine style skiing opportunities. With gold having been found in the vicinity, Breckenridge was thronged with prospectors, some with money, who were hungry for fresh bread and pastry. Probably with some early experience in the trade, Kellenberger started a bakery. Either because this enterprise was not successful or because he sought more lucrative opportunities, after two years he closed up shop and headed to Southern California.

Kellenberger, shown here about 1901, was born in 1861 and came to the United States in 1880. After landing in New York City, the young Swiss made his way to Brechenridge, Colorado, perhaps drawn there by the similarities in the landscape of his homeland that promised Alpine style skiing opportunities. With gold having been found in the vicinity, Breckenridge was thronged with prospectors, some with money, who were hungry for fresh bread and pastry. Probably with some early experience in the trade, Kellenberger started a bakery. Either because this enterprise was not successful or because he sought more lucrative opportunities, after two years he closed up shop and headed to Southern California.

Upon arrival on the West Coast he served an apprenticeship in wine making, an industry in which many Swiss immigrants were engaged. Kellenberger clearly had a talent for wine. It is reported that during his ten years in California he established wineries at three sites south of Los Angeles. He also ran a saloon in Santa Ana. Ignoring a local ordinance against Sunday sales, he was caught by the local police for selling liquor out the back door. Hauled into court he was fined $40 for his indiscretion. The Los Angeles Herald commented: “Kellenberger didn’t like to pay the fine, but he did so and now he is a sadder but much wiser man.”

As he “wised up,” Kellenberger decided to return to Colorado. During his California sojourn he had met an Austrian immigrant woman named Marie who was nine years his junior. She is said to have been a woman of considerable culture, speaking five languages including German, French and Italian. They married and a daughter, Lydia, was born in 1892, just in time to join the family move to Durango, Colorado. This settlement, nestled in the Animas River Valley and surrounded by the San Juan Mountains, had been founded by the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad to serve nearby mines. Durango too might have reminded John of his Alpine roots. Perhaps the same held true for Marie. A second child, Erma, was born not long after they arrived.

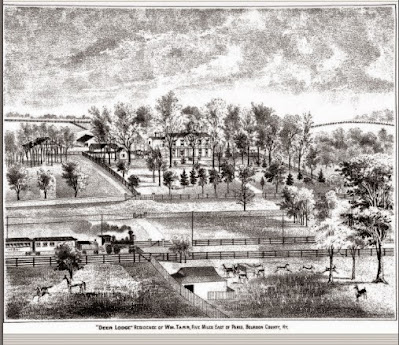

Durango, named after a town in Mexico (in turn, after a town in Spain), literally means “water town.” As a place where mine workers dwelled, however, something strong than water was their preference, and Kellenburger was eager to supply it to them. With the money he had saved in California he opened a liquor and cigar store and saloon at 951 Main, the major commercial street, shown above as it looked in the late 1800s.

Kellenberger’s drinking establishment was like nothing Durango had ever seen before. The front windows, shown above, were crammed full of whiskey bottles together with the owner’s eccentric collection. As can be seen, it included a stuffed dog, owl and pistol packing bear. Other items included violins, ore samples, a snakeskin and a scalp. Seen below, the bar was dark mahogany with a brass rail and an array of saloon signs behind the bartenders. Note the spit bucket on the floor. Sales were conducted in a rear room where whiskey could be bought by the barrel or the bottle.

Kellenberger’s drinking establishment was like nothing Durango had ever seen before. The front windows, shown above, were crammed full of whiskey bottles together with the owner’s eccentric collection. As can be seen, it included a stuffed dog, owl and pistol packing bear. Other items included violins, ore samples, a snakeskin and a scalp. Seen below, the bar was dark mahogany with a brass rail and an array of saloon signs behind the bartenders. Note the spit bucket on the floor. Sales were conducted in a rear room where whiskey could be bought by the barrel or the bottle.

Kellenberger was not just buying finished and bottled products, but “rectifying” whiskey; that is, buying raw liquor in large quantities from distillers, probably in California, then blending and compounding it to taste in a back room of his store. Much of his whiskey he sold in large ceramic jugs, gallon and half-gallon sizes. Ever canny, he recognized that the Kellenberger brand could get recognition just by exhibiting at various international expositions. That reputedly gained him medals at New Orleans in 1885, Chicago in 1893 and Paris in 1900. He also was bottling beer and created a delivery system for his products throughout Colorado and Northern New Mexico.

The personality of a Western saloon owner was crucial to its success and Kellenberger had personality to burn. Not only was his “Whoop-E-Tee-Whoop” greeting to his customers a source of conversation for Durango locals but, according to Historian Kathy Myrick, stories abounded about him and his cronies taking train trips while playing cards and lunching on fine cheeses, bread and smoked tongue he supplied. The February 1903 Mining Reporter listed Kellenberger recording a claim for a mineral lode near Durango at a mine he whimsically called “Canary Bird.”

The personality of a Western saloon owner was crucial to its success and Kellenberger had personality to burn. Not only was his “Whoop-E-Tee-Whoop” greeting to his customers a source of conversation for Durango locals but, according to Historian Kathy Myrick, stories abounded about him and his cronies taking train trips while playing cards and lunching on fine cheeses, bread and smoked tongue he supplied. The February 1903 Mining Reporter listed Kellenberger recording a claim for a mineral lode near Durango at a mine he whimsically called “Canary Bird.”

Like many saloonkeepers Kellenberger was lavish with giveaway items including bar tokens. In additional to the $1 token that opens this vignette, he handed out 12 and 1/2 cent ducats that had his name on one side and a pictorial of the Durango smelter and grazing deer stamped on the other. The tokens have been dated about 1897. Still another attractive gifted item was a clear glass back-of-the-bar bottle with gold lettering advertising “John Kellenberger…Wholesale Liquor…Durango, Col.”

Like many saloonkeepers Kellenberger was lavish with giveaway items including bar tokens. In additional to the $1 token that opens this vignette, he handed out 12 and 1/2 cent ducats that had his name on one side and a pictorial of the Durango smelter and grazing deer stamped on the other. The tokens have been dated about 1897. Still another attractive gifted item was a clear glass back-of-the-bar bottle with gold lettering advertising “John Kellenberger…Wholesale Liquor…Durango, Col.”

Kellenberger’s time in Durango encompassed the worst disaster in the town’s history. An historic rainfall in October 1911 turned the Animas River into a torrent that destroyed crops, washed away more than 100 bridges and damaged some 300 miles of railroad tracks. Lives were lost as fifteen feet of water rushed through Durango streets. Kellenberger was in Telluride 120 miles away when the torrent hit. Anxious to return home, he tried many several routes, finding each of them washed out and impassable. He finally was able to telephone the Durango Evening Herald for a report on conditions. “John Kellenberger phones in from Telluride that he is now doing a ring-around-the-rosy act,” the paper quipped.

Meanwhile, another torrent was rising. The forces of prohibition were closing in on Colorado and the liquor trade. Kellenberger saw them coming and in 1915, just before the state went dry, he bought the Durango Bottling Works. Subsequently he was forced to close his saloon and the liquor store, shown above. Then he and his employees simply moved down the street, exchanging hard drinks for soft. Shown here about 1916 is a train car apparently full of Kellenberger’s “Raspberry Julep” bound for Leadville, Colorado. Once laced with alcohol, his julep recipe had reappeared as “soda pop.”

Although Kellenberger had left California apparently wiser about breaking the law, the advent of prohibition in Colorado caused him to hatch another scheme. He went to still “wet” New Mexico, near the small town of Chama, and is believed to have buried a supply of his whiskey. According to Historian Myrick, in 1916 he attempted to smuggle liquor back into Colorado in a train car with a bill of lading that gave the contents as “hay.” Once again, the authorities caught him, penalty unknown. Legend has it that some of Kellenberger’s stash may still lie underground somewhere in New Mexico near the Colorado border.

After this incident, Kellenberger seemingly reconciled himself to producing and selling only non-alcoholic beverages. He bought the Adolph Coors building in Durango, built originally as an adjunct to the brewing family’s Golden headquarters. Obtaining the first Coca-Cola franchise in the region, he converted the building to a successful Coke bottling plant. In the 1920 U.S. census, his occupation was recorded as “merchant, wholesale cigars and beverages.” He and Marie still were living in their spacious Durango home at 827 Third Avenue at the Boulevard.

After this incident, Kellenberger seemingly reconciled himself to producing and selling only non-alcoholic beverages. He bought the Adolph Coors building in Durango, built originally as an adjunct to the brewing family’s Golden headquarters. Obtaining the first Coca-Cola franchise in the region, he converted the building to a successful Coke bottling plant. In the 1920 U.S. census, his occupation was recorded as “merchant, wholesale cigars and beverages.” He and Marie still were living in their spacious Durango home at 827 Third Avenue at the Boulevard.

Although I have been unable to find information on Kellenberger’s death and burial site, a fitting memorial to this whiskey man was provided in a 1901 article that described the Swiss immigrant as: “…A public spirited man, one who stands very high in business circles in Durango and throughout the State. He is liberal and progressive…benefits his community by his enterprise and pluck.” And, it must be added, he greatly entertained his fellow citizens by his “Whoop-E-Tee-Whoop.”

Note: I was in the process of researching a post on Kellenberger when I came across a current article on him by Kathy Myrick in the Winter/Spring 2014-2015 issue of Durango Magazine, published in that city. I have included here some information and three photos of Kellenberger’s saloon from her article as “fair use,” because I strongly advise anyone interested in Kellenberger or Durango to buy the magazine, which has a number of excellent articles, including hers. It also has interesting ads and is well worth the price. Check the magazine website. An aside: Although I have never been in Durango, the nickname “Jocko-from-Durango” was given to me in 1958 by a newspaper editor for reasons too complicated to go into here. I have used it as a “nom de plume” on numerous occasions and have always wanted to visit the city itself.

_2-1.jpg-%2Bc.jpg)