On Friday, May 7, 1915, during World War One, a German U-Boat torpedoed the Cunard ocean liner RMS Lusitania eleven miles off the coast of Ireland. The vessel caught fire and sank in eighteen minutes. Only 723 passengers and crew survived. Killed were 1,198 passengers and crew, including 128 Americans. Among them was Victor E. Shields, a prominent Cincinnati liquor dealer, and his wife Retta.

Shown here is the passport photo of Shields as he prepared to board the Lusitania in New York. He gave his occupation as “merchant” never mentioning liquor and said his purpose was “commercial business” with his destinations being England, France and Italy. In truth, it was also a pleasure trip with his wife of 19 years. It was the first time either had ever seen Europe and traveling there first class in one of world’s most luxurious liners must have been exciting and full of anticipation for the couple. They were just hours from docking in England when disaster struck.

Shown here is the passport photo of Shields as he prepared to board the Lusitania in New York. He gave his occupation as “merchant” never mentioning liquor and said his purpose was “commercial business” with his destinations being England, France and Italy. In truth, it was also a pleasure trip with his wife of 19 years. It was the first time either had ever seen Europe and traveling there first class in one of world’s most luxurious liners must have been exciting and full of anticipation for the couple. They were just hours from docking in England when disaster struck.

Forty-five years earlier Victor had been born in Charleston, West Virginia, the son of Fredericka (nee Scheldesheim) and Joseph Shields. When he was only a toddler, his father moved the family to Cincinnati, where Victor was joined by a brother, Percy, in 1874 and a sister, Rosa, in 1877. About 1873 his father with a partner set up a Cincinnati wine and spirits company called Shields, May & Co., located at 17 Sycamore Street.

The liquor house featured a number of brands, including "Fountain Run Still,” “Gincocktail,” "Gold Finch,” "Hunter's Own Bourbon.” "Jefferson Pure Old Rye,” "May Bloom Pure Copper.” "Old Wheat.” “Shields' Mountain Rye,” and “Shields’ Maryland.” Of these the company trademarked only three, May Bloom in 1874 and Hunter’s Own and Jefferson Pure Old Rye in 1875.

The liquor house featured a number of brands, including "Fountain Run Still,” “Gincocktail,” "Gold Finch,” "Hunter's Own Bourbon.” "Jefferson Pure Old Rye,” "May Bloom Pure Copper.” "Old Wheat.” “Shields' Mountain Rye,” and “Shields’ Maryland.” Of these the company trademarked only three, May Bloom in 1874 and Hunter’s Own and Jefferson Pure Old Rye in 1875. Beginning about 1878, Joseph Shields was operating without a partner and also advertising his services as a “whiskey broker and distiller’s agent,” located at 97 Main Street in Cincinnati. For the next two decades he would operate a successful liquor business. When his son Victor was grew into manhood, Joseph did not immediately take him into the firm, but secured his apprenticeship as a traveling salesman with the Turner-Look Company, another Cincinnati liquor outfit. [See my post on this firm, December 4, 2917.]

Beginning about 1878, Joseph Shields was operating without a partner and also advertising his services as a “whiskey broker and distiller’s agent,” located at 97 Main Street in Cincinnati. For the next two decades he would operate a successful liquor business. When his son Victor was grew into manhood, Joseph did not immediately take him into the firm, but secured his apprenticeship as a traveling salesman with the Turner-Look Company, another Cincinnati liquor outfit. [See my post on this firm, December 4, 2917.]

In 1896, Victor wed Retta Cohen in Hamilton, Ohio, a suburb of Cincinnati. He was 26, she was 24. Their marriage would be childless. About the same time as his marriage, he joined his father’s liquor firm, taking over the business when Joseph decided to invest his time and money in other enterprises, subsequently founding the Shields Oil & Gas Company. Victor lost little time in renaming the organization V.E. Shields & Company, eventually moving from Main Street to 117-121 East Pearl, as shown on his letterhead.

The younger Shields had his own set of brands, many likely “rectified” (blended) from Kentucky distilled whiskies readily available in Cincinnati, just across the Ohio River, or from upriver in Pennsylvania. His labels included "Buck Eye Club,” "Cream of Pennsylvania,” “Elmwood.”, "First Premium,” "Lehigh Rye,” “Pilot,” "Shields Maryland XXXX,” and "White Squadron.” He packaged his whiskey in glass bottles, ranging from flasks to quarts. There is no evidence Victor trademarked any of his brands, except a claim for the bottle design shown below right.

The younger Shields had his own set of brands, many likely “rectified” (blended) from Kentucky distilled whiskies readily available in Cincinnati, just across the Ohio River, or from upriver in Pennsylvania. His labels included "Buck Eye Club,” "Cream of Pennsylvania,” “Elmwood.”, "First Premium,” "Lehigh Rye,” “Pilot,” "Shields Maryland XXXX,” and "White Squadron.” He packaged his whiskey in glass bottles, ranging from flasks to quarts. There is no evidence Victor trademarked any of his brands, except a claim for the bottle design shown below right.

Like many liquor dealers, Shields rewarded the saloon, restaurants and hotels featuring his products, as well as regular retail customers, with give away items. Two of his were mini ceramic jugs, each of them holding a swallow or two of whiskey. Brands they advertised included Lehigh Club and Maryland XXX, both rye whiskeys. For twenty years Victor manage his liquor business with great success, its profitability likely leading to the fateful decision to venture abroad with his wife.

Like many liquor dealers, Shields rewarded the saloon, restaurants and hotels featuring his products, as well as regular retail customers, with give away items. Two of his were mini ceramic jugs, each of them holding a swallow or two of whiskey. Brands they advertised included Lehigh Club and Maryland XXX, both rye whiskeys. For twenty years Victor manage his liquor business with great success, its profitability likely leading to the fateful decision to venture abroad with his wife.

The sudden deaths of his son and daughter-in-law seemingly dealt a crushing blow to Joseph Shields, now 81. He had been involved in the couple’s planning for the trip, writing a letter of endorsement to accompany their passport application. Moreover, death also had come to the family only a year earlier when his second son, Percy, 40 years old, had died. Still an officer of the Shields liquor firm, Joseph shut it down after some fifty years in business. Less than a year after the sinking of the Lusitania, perhaps burdened with sorrow, Joseph himself died in 1916 at age 82 and was buried in the family plot.

The story does not end there. International law dictated that the heirs of any citizens of non-belligerent countries killed in warfare must be compensated. Although German authorities initially rejected that responsibility, after World War One a defeated Germany provided the U.S. with a large settlement to be divided up among families of the dead. The Joint U.S.-German Commission designated to make the payments was petitioned by the Shields’ estate for compensation. The prospect of “blood” money, however, set Victor’s next of kin at odds with Retta’s. The Commission in its 1924 judgment described their conflicting appeals:

“It is urged that as Mr. Shields was two years older than his wife, she would, but for the wrongful act of Germany in sinking the Lusitania, have probably survived him and would then under his will have inherited his entire estate…and that her next of kin would have ultimately benefitted thereby.

“On the other hand, Mr. Shields’ next of kin urge that his ‘wife having perished with him on the Lusitania, there is no room for doubt that if he had survived,’ he, being then without wife or children, would have been generous in his contributions to them.”

In making its decision, the Commission noted the wealth of the couple. Victor had an annual income equivalent today to about $200,000 year and left an estate equivalent to $2.8 million. On the same scale, Retta’s estate was worth an additional $600,000. The Commission noted that because none of the claimants had suffered losses as a result of the deaths of the Shields [and in fact already had benefited from their inheritances] their claims furnished “no sound basis on which to rest a award.” The relatives got nary a pfennig of Lusitania compensation.

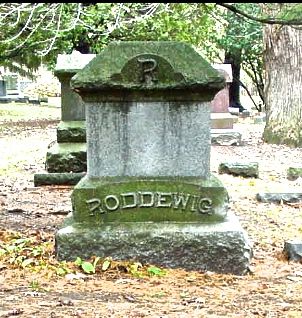

It is unclear whether the bodies of Victor and Retta were recovered. Not long before he died, Joseph Shields arranged for gravestones for Victor and Retta to be installed at the Walnut Hills Cemetery in Hamilton County. Shown above, they remain a reminder of the Shields’ personal tragedy, one among many, that ultimately led to U.S. participation in World War One.