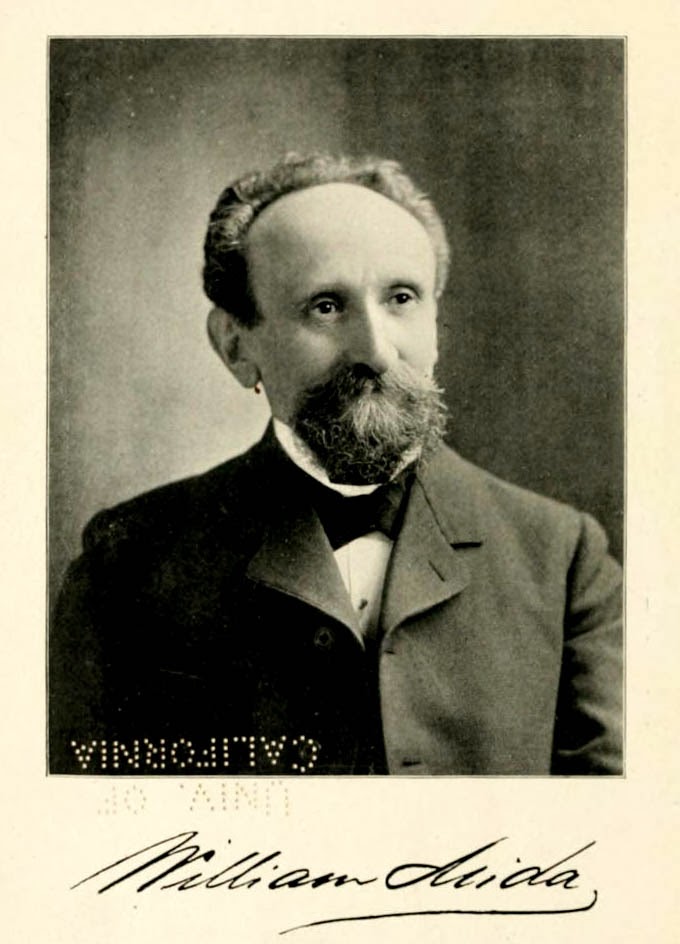

High praise, indeed, but a century later his name has faded into the background even as names like Daniels, Bernheim, Taylor, Weller, and Van Winkle continued to be remembered. Why? Although he also made whiskey, Mida’s reputation rested on his work in liquor laws and trademarks, much of it wiped out by National Prohibition.

Mida was born in Warsaw, then part of Russian-occupied Poland, in July, 1839. He came from a wealthy Jewish family that was able to give him an excellent education. In addition to his schooling in Poland, he also studied the classics, mathematics and literature in Germany and France and spoke five languages, including English. Although there is no indication he had a law degree, his education clearly fit him for the tasks he later would undertake.

While in his early 20s, like many well educated Poles, Mida joined the Rebellion of 1863, a eventually unsuccessful effort by Polish partisans, shown here, to rid themselves of Russian domination. During the fighting he was captured and imprisoned. Eventually pardoned he made his way to Germany where he became revolutionary agent, aiding in smuggling arms from France into Poland. When his clandestine work on behalf of the Polish resistance was discovered, he was forced to escape to England.

In 1867 he came to the United States and after a few months in New York moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he likely found employment in one of the many liquor dealerships run by Jewish immigrants from Europe. It was in Cincinnati that William became a naturalized American citizen and met the woman who would become his wife. She was Lena Cahn. They would have one son, Lee, and be married for almost 40 years.

Mida may have made an initial move to St. Louis. A business directory there for 1872 lists him as a liquor dealer. He did not stay long in Missouri. About 1873 Mida and his family moved to Chicago which would be their permanent home. During his stay in Ohio Mida seemingly had learned the craft of the whiskey rectifier, blending and compound whiskeys to render them smoother and more mellow. His wholesale liquor dealership first shows up in Chicago directories in 1880. He early located his business at 93 Washington Street but soon moved to 46-48 Clark Street and, apparently needing more space, to Dearborn Avenue, shown here, a major Chicago business hub. He featured several proprietary brands including “Relish” and “Mida’s Confidential.”

While this trade apparently was lucrative, Mida’s restless mind saw a grave need in America’s liquor industry and determined to fill it. In 1883 he published “Mida’s Handbook for Wholesale Liquor Dealers.” Its success encouraged him to publish an informational semi-monthly journal devoted to the trade, much of it devoted to state liquor laws. He called it “Mida’s Criterion” and published it for nearly three decades. The success of the magazine prompted Mida to establish a publishing house, called Criterion Press. In quick succession he issued a number of publications.

Perhaps the most famous of them was “Mida’s National Register of Trade-Marks, published in 1893, with a second volume in 1895 and a combined volume in 1898. During that period trademarks were a dicey proposition. A tough 1870 law had been struck down as interference with interstate commerce. Disputes over whiskey brand names were common and judges generally were unwilling to enforce the laws that existed if any home state interests were involved

Into this situation stepped William Mida. He believed that the trademarking of brands was a key to the orderly growth of the whiskey industry and in his register listed the several hundred trademarks that already had been recorded with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Many had also registered them with Mida and his “Trade Mark Bureau.” Most marks were illustrated as barreled designs but he also included registration of advertising items such as labels or pocket mirrors. There

also were several dozen pages of advertising at the end of the book. Ads included full pages for liquor wholesalers like Freiberg & Workum. Those likely helped to defray the cost of a volume that ran to 300 pages and was priced at a hefty (for the times) $10.

also were several dozen pages of advertising at the end of the book. Ads included full pages for liquor wholesalers like Freiberg & Workum. Those likely helped to defray the cost of a volume that ran to 300 pages and was priced at a hefty (for the times) $10.Mida’s work was valuable in letting other whiskey men know what brand names had been registered. The index was by brand name, not company and thus easy to reference. He also was pushing the importance of registration to the liquor trade. Thus when a stronger trademark law was passed in April 1905, it gained general acceptance among distillers and rectifiers. Mida, true to his code, trademarked his Relish Whiskey in 1905 and Mida’s Confidential in 1907.

At the same time he was trying to make sense for the liquor industry of the blizzard of federal and state laws, ever-changing and often reflecting the work of prohibition forces. In “Mida’s Compendium” (1889) and later “Mida’s Compilation of State and Federal Pure Food Laws” (1906), he parsed the laws and tried to answer questions about their application. He often did this in a question and answer format.

One of his responses cleared up a problem I have pondered: “May the name “distilling company” be used on a sign by company not distilling?” Rectifiers often called themselves distillery companies although they used someone else’s whiskey. Yes, they can, Mida declared in his Compendium. When a firm is incorporated and is authorized to conduct business as a distilling company, a firm can made use of its legal application, he explained. But to advertise as a “distiller” would be a violation of Federal law, he cautioned, and the user would be liable to a penalty.

Among the many other publications Mida generated was a compilation of registered canned food brands. Arranged by state and brand names under headings such as the one shown here, it was another exhaustive look at an area of trademarking. This time there were no pictures. Although Mida regularly had railed against the force of Prohibition in the Criterion, in 1913 he launched a periodical explicitly aimed at fighting the

“drys.” He called it “Mida’s Epitome.”

“drys.” He called it “Mida’s Epitome.”That publication proved to be short-lived. In October 1915 William Mida died, age 76. He had been preceded in death by his wife, Lena, in 1909. The work he had begun on trademark and law through Mida’s Trade Mark Bureau was continued unabated by his son, Lee. In 1918 the son published a volume entitled “Trade Mark Protection and Penalties under State Registration Laws.”

Lee Mida and his wife were well known in Chicago sporting circles. Lee won the Chicago City Golf Championship in 1919. His wife (nee Lucia Gueth) became even more recognized. Playing under the name Mrs. Lee Mida she won the 1930 Women’s Western Open, which later was designated by the LPGA as the first women’s major. With her husband’s death the

trade mark business passed to his widow who leased it to others. It survived into the 1950s when charges of ethics violations against its proprietors caused it to close.

trade mark business passed to his widow who leased it to others. It survived into the 1950s when charges of ethics violations against its proprietors caused it to close.Despite William Mida’s effort to thwart Prohibition, it came in 1920. Many of the liquor brands and most of the companies he listed went out of existence. The information his books contained quickly became obsolete. Unfortunately, for all his belief in trademarking, Mida never copyrighted his liquor trademark books. Not even the Library of Congress has a copy. The Filson Museum in Louisville owns one and several are in private hands. Most of his other publications also have long since faded from view. Nevertheless, his legacy for the American liquor trade was a highly significant one. To paraphrase his obituary, during his lifetime William Mida, did, indeed, do much to advance its interests.

Note: An acknowledgment to Howard Currier for his article on the Mida trademark books in the February 2003 issue of Bottles and Extras, the publication of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors. His treatment suggested to me that a closer look at the man, William Mida, would be a good addition to this blog. And it is.

+2%22:1-5:8%22-+c.jpg)