The four brothers were the sons of Simon and Sophia Steinhardt. The parents were born in Austria and, if census data is accurate, moved to Germany where Lewis and Morris were born. Sometime between 1853 and 1857 the family emigrated to the United States, settling in Manhattan. All their other six children would be born in New York.

Simon seems to have forged a business career in his adopted country. The 1870 census found him, Sophia and all eight children living on 16th Street between First Avenue and Avenue A. Simon gave his occupation as cigar merchant. By the time the next census was taken, things had changed significantly. Lewis and Morris were no longer in the home but not recorded in other census data. The rest of the family was still together, but Simon, 59, and the two remaining sons, Henry, 22, and David, 18, all listed their occupation as “liquor dealer.”

And well they might have. 1880 marked the year that Steinhardt Bros. & Company first showed up in New York Business directories. Their initial location was 456-458

Greenwich Street. Lewis, the eldest Steinhardt appears to have been the top manager there. Another location opened that same year and was listed at 192 Division Street.

Greenwich Street. Lewis, the eldest Steinhardt appears to have been the top manager there. Another location opened that same year and was listed at 192 Division Street. There followed a proliferation of stores. In 1885, a Steinhardt location was listed for 313-315 Bowery. David Steinhardt was recorded as manager there. In 1890 stores were at 87-93 Hudson, that Morris apparently was running, and at 2259 Second Avenue, the Harlem Branch. A 1991 Steinhardt calendar cited the Bowery and Second addresses adding 299-301 Patchen Av., corner of Chauncy Street, in Brooklyn. In a 1902, a business directory shows the Steinhardts at 2207 Third Avenue and 134-138 Mott Street. A 1903 directory lists an outlet at 29 Ninth Street. With four brothers and apparently for a time their father, the Steinhardts could run multiple liquor stores. Henry, for example, is listed as having a shop at 143 Broome.

The Steinhardts were not distillers. They collected whiskey from a variety of sources, “rectified” (mixed), probably at their Mott St. facility. Now considered part of Chinatown, Mott in the early 1900s was a hotbed of new immigrants from Europe. The brothers sold their liquor both nationally and from outlets in New York. For example, Roxbury Rye, one of the Steinhardt’s flagship labels, was a made in Maryland by George Gambrill [See June 2011 post]. Hauled into court by a disgruntled employee, Gambrill made the bizarre claim that he was not in the distilling business since his entire product for five years -- 3,000 barrels of whiskey -- had been consigned to the Steinhardt Brothers and that, in effect, the Steinhardts owned his distillery. The court rejected that defense out of hand. Roxbury Rye deal apparently held, however, and the label was heavily advertised by the Steinhardts.

Other Steinhardt brands were “Littlemore,” “Old Methusalem,” “Hill Side,” “Lafayette Club Old Rye,” ”Old Ballymore,” “Hill Brook,” “The Kintore,” “Emerald Brand,” “Mountain Dew” and

“White Lily Pure Rye.” Like many whiskey dealers of their time the Steinhardts featured lots of giveaways to favor customers. If you stocked their Littlemore “whiskey of merit” in your saloon, their largesse might include colorful lithographed tip trays or a wooden wall clock. For Hill Side Rye, the Steinhardts

“White Lily Pure Rye.” Like many whiskey dealers of their time the Steinhardts featured lots of giveaways to favor customers. If you stocked their Littlemore “whiskey of merit” in your saloon, their largesse might include colorful lithographed tip trays or a wooden wall clock. For Hill Side Rye, the Steinhardts  gifted a reverse glass sign.

gifted a reverse glass sign.

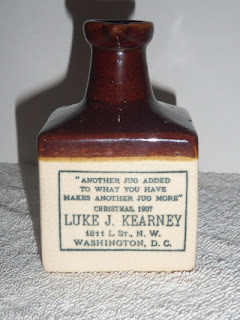

What initially drew my interest to the Steinhardts, however, was not their giveaways but the quality of the ceramic containers in which they packaged their liquor. They had a “fancy for the fancy.” A prime example is the White Lily jug. This container was the product of the Knowles, Taylor and Knowles Pottery of East Liverpool, Ohio. The white semi-china jug is known in three colors -- blue, red and green -- of which the green is the most common. All three have a round yellow monogram in the lower left corner. About the size of the new dollar coin, the mark shows a tiger-like beast

pierced through by a spear on which is written “trade mark.” Below are the initials “S.B. & C.” The Steinhardt brothers featured this whiskey a great deal in their merchandising. In addition to displaying an illustration on their case labels, an artist’s rendering of the KT&K jug also was featured on their annual calendars.

pierced through by a spear on which is written “trade mark.” Below are the initials “S.B. & C.” The Steinhardt brothers featured this whiskey a great deal in their merchandising. In addition to displaying an illustration on their case labels, an artist’s rendering of the KT&K jug also was featured on their annual calendars. But this New York City outfit didn’t stop there. In the early part of the 1900s, it ordered up -- likely from Sherwood Bros. pottery of New Brighton, Pennsylvania -- another series of very fancy whiskey jugs. Among them was one furnished for their Kintore “Scotch.” Its underglaze label features Scottish thistles, a coat of arms topped by a crown that seems vaguely old country, and the Steinhardt name in script.

Not shown here were “twin” ceramic containers. They were matching jugs of which one appeared to contained Irish whiskey and the other Scotch. Neither jug, however, was explicit about its contents. Both Emerald Brand and Mountain Dew are cited on the label as “a blend of whiskey.” The former boasts an “art nouveau” label with shamrocks rampant and a woman playing a harp in a circle at the center, indicating Irish whiskey. The other is similar but its motif is thistles and a wolf-like creature, indicating Scotch. Steinhardt Bros. & Co. New York is identical on both ceramics. Those probably were meant to be placed next to each other on the liquor store shelf and to entice the customers by standing out from spirituous products in glass containers.

Lavish giveaways and fancy jugs could not save Steinhardt Bros. & Co. from the inroads of Prohibition. As state after state went dry, the company’s mail order business suffered repeated blows. By 1915, if New York directories are accurate, the brothers were down to one outlet, at 29 Ninth Street. In 1918 all mentions of the firm disappear. By this time Lewis was 67 years old and Morris 65. Time to retire. It had been a 38 year run of business success in the Big Apple. To paraphrase the song, “New York, New York:” If they could make it there they could make it anywhere.