Many books on Kentucky whiskey history while extolling the Beams, Bernheims and Browns say nary a word about the Willetts, despite the family having been involved in distilling in the Blue Grass State from the mid-1800s, surviving National Prohibition and functioning even today. Their story is one of a family’s love for the distiller’s craft and a united determination to succeed.

The Early Willetts

One of the first known Willetts in America was Thomas Willett who landed from England at Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1632. The family was Catholic, under heavy pressure from the Church of England founded by King Henry the Eighth. Except for the Maryland Colony, founded by Catholics, the New World welcome was mixed. Like other of their faith the Willetts migrated there, for the next 100 years settling in Prince George’s County, just outside of what would become the District of Columbia.

William Willett Sr. was the first of the Willett family to get into the distilling business after he married his wife Mary in 1738 in Maryland. In Mount Calvert, Maryland, near the Patuxent River, William Senior owned a tavern and began distilling a liquor he called "Maryland Rye Whiskey.” Principally farmers, those Maryland residents eventually found the soil increasingly depleted and many headed west to claim land in Kentucky. Among them was William Willett Jr, who had had learned the distillers trade as a mere boy and eventually was entrusted by his father with the business. He took that knowledge with him when he migrated to Nelson County in 1792, the year Kentucky became a state. The county and its seat, Bardstown, thereafter would be intertwined with the Willett name. Because of the many Catholics and religious orders that settled in and around the town, it became known as “The Little Vatican.”

The Formative Willetts

John David Willett, William’s son, born in Bardstown in 1841, having learned the distilling trade from his father, from an early age was heavily involved in whiskey making activities. By this time the Willetts were one of the oldest families in the Kentucky whiskey business and seen as wealthy. John David was one of eight children, five sons and three daughters. He received a good education for the times and alone among his siblings inherited the family distilling properties.

John David Willett, William’s son, born in Bardstown in 1841, having learned the distilling trade from his father, from an early age was heavily involved in whiskey making activities. By this time the Willetts were one of the oldest families in the Kentucky whiskey business and seen as wealthy. John David was one of eight children, five sons and three daughters. He received a good education for the times and alone among his siblings inherited the family distilling properties.

Meanwhile John David had caught the eye of Mary Alice Moore, the daughter of Charles A. and Catherine (Kate) Ann Moore. Like the Willetts, the Moores were among the Catholic families who had left Maryland for the greener pastures of Kentucky. The two, of a similar age, likely knew each other from childhood. They married about 1874, both 24 years old. Over the next 14 years Mary Alice Moore Willett, shown above, would bear seven children, under pioneer circumstances. All of them lived to maturity, several to advanced ages.

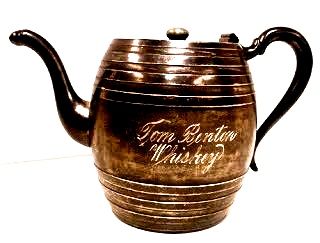

In the late 1860s John David formed a new distilling company in Bardstown with his wife’s brother, Thomas S. Moore, and third partner from Louisville. He became the master distiller for the Louisville based plant, known as Moore, Willett & Frenke. John Davd also is reputed to have owned a second distillery Little is known about this facility, other than its location at Morton’s Spring just south of Bardstown. Under later ownership that distillery is reported to have had a capacity of mashing 250 bushels per day and warehousing 7,500 barrels.

In 1876, Willett, said to be in failing health and eyesight, and sold his interest in the company to Moore and Ben Mattingly who had married one of his daughters. The resulting company became the Mattingly Moore Distillery. Their flagship brand was “Belle of Nelson,” named for John David Willett's winning racehorse. [See post of September 3, 2017.]

Willett unexpectedly lived for another 38 years after this transaction. During that period he reputedly was the master distiller at four other Kentucky distilleries. He died in 1914. According to his death certificate the cause was a heart attack. Following a funeral Mass thronged with family members and friends, John David was buried in Bardstown’s St.Joseph Cemetery, Section A, Row 27, Grave 15, the marker shown below. He would be joined 17 years later by his widow, Mary Alice.

Aloysius Lambert Willett, who went by “Lambert,” was born in September 1883 in Bardstown, the fifth in the line of John David and Mary Alice’s children and the second son. Like other Willetts before him Lambert had his initiation into the wonders of distilling as an adolescent. At age 15 Lambert went to work for the distillery his father had founded as an apprentice, now owned by Mattingly and Moore. He then moved to Louisville to work for the Max Selliger & Co. Distillery for the next 20 years, eventually becoming a one-third owner and superintendent of the plant. [See my post on Selliger, May 18, 2017.]

Aloysius Lambert Willett, who went by “Lambert,” was born in September 1883 in Bardstown, the fifth in the line of John David and Mary Alice’s children and the second son. Like other Willetts before him Lambert had his initiation into the wonders of distilling as an adolescent. At age 15 Lambert went to work for the distillery his father had founded as an apprentice, now owned by Mattingly and Moore. He then moved to Louisville to work for the Max Selliger & Co. Distillery for the next 20 years, eventually becoming a one-third owner and superintendent of the plant. [See my post on Selliger, May 18, 2017.]

In April 1908, Lambert married Mary Catherine Thompson in Bardstown. Over the next 25 years they would have seven children, six sons and one daughter. Lambert’s eldest boy, known as Thomson Willett, at a very early age was introduced into distilling at the Selliger facility. Like other whiskey producers the coming of National Prohibition caused the Louisville plant to be “idled” for the following years. Returning to Bardstown bought land near and began working as a farmer.

After Repeal of Prohibition, his sons demonstrated an interest in restoring the Willett name as a force in Kentucky whiskey-making. Lambert offered the farm as the site and helped finance the construction of a new distillery. They named it the Willett Distilling Company. Once the facility was up and running, Lambert became involved in the family enterprise full-time. He remained actively interested in distilling for much of the rest of his 87 years, dying in 1970. He lies buried in St. Joseph Cemetery, not far from his parents and other members of the Willett clan.

Aloysius L. Thompson Willett, known as “Thompson” all his life, was born Bardstown in 1909, the first child of Lambert and Mary Catherine. Three years after the repeal of Prohibition in 1936, at the age of 27, Thompson, shown here, assisted by brother Johnny “Drum” Willett, spearheaded the construction of a new distillery on their father’s farm. Nine months later the facility, shown in an artist’s rendering below, produced its first 30 barrels of whiskey. Fittingly it was on St. Patrick’s Day when they stored the first barrels for aging in the new warehouse. This liquor is recorded to have been distilled following a recipe developed by Thompson’s grandfather John David Willett.

Aloysius L. Thompson Willett, known as “Thompson” all his life, was born Bardstown in 1909, the first child of Lambert and Mary Catherine. Three years after the repeal of Prohibition in 1936, at the age of 27, Thompson, shown here, assisted by brother Johnny “Drum” Willett, spearheaded the construction of a new distillery on their father’s farm. Nine months later the facility, shown in an artist’s rendering below, produced its first 30 barrels of whiskey. Fittingly it was on St. Patrick’s Day when they stored the first barrels for aging in the new warehouse. This liquor is recorded to have been distilled following a recipe developed by Thompson’s grandfather John David Willett.

The Willett Distillery from the outset appears to have been successful, even though it opened in the depths of the Great Depression. In 1942, Thompson, despite wartime restrictions, issued the distillery flagship brand, “Old Bardstown Bourbon,” a label that later would win a gold medal at a Kentucky bourbon competition. After World War II, two other brothers, Paul and Bill, both of whom had served in the Army Air Force, joined the company, Paul in charge of bottling and Bill in distilling operations.

Meanwhile Thompson, shown here on the day of his wedding, was having a personal life. After an extended bachelorhood, in 1942 at the age of 33 he married Mary Virginia Sheehan, 26. They would have at least three children. The first, a girl, died after her premature birth. The second, James, a son bearing both the Lambert and Thompson names, died at only 26, grieving both father and mother. A second daughter, Harriet, lived to maturity.

From the beginning, Thompson devoted himself wholeheartedly to the success of Willett Distilling, serving as president until 1984 when he was 75. His stature in the distilling community rose steadily and he served for a time as president of the Kentucky Distillers Association. Shown here outside one of his warehouses, Thompson was an active member of the Nelson County Historical Society, where his interests included the history of whiskey-making in Kentucky. Thompson lived to be 92, dying in March 2001. Aftr a funeral Mass he was buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, not far from his ancestral Willetts. Shown below, his gravestone is engraved “Master Distiller, Willett Distillery.

From the beginning, Thompson devoted himself wholeheartedly to the success of Willett Distilling, serving as president until 1984 when he was 75. His stature in the distilling community rose steadily and he served for a time as president of the Kentucky Distillers Association. Shown here outside one of his warehouses, Thompson was an active member of the Nelson County Historical Society, where his interests included the history of whiskey-making in Kentucky. Thompson lived to be 92, dying in March 2001. Aftr a funeral Mass he was buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, not far from his ancestral Willetts. Shown below, his gravestone is engraved “Master Distiller, Willett Distillery.

The Willett Inheritors

Under Thompson’s watchful eye, Willett Distilling continued to make whiskey into the 1970s. During the 1970s energy crisis, the company switched from making whiskey to producing ethanol for gasohol fuel. When energy prices slumped, the strategy failed. The facility was entirely shut down in the early 1980s. Thompson Willett's daughter, Martha, was among those who had worked for the distillery and regretted its demise.

In 1972 Martha married Even (pronounced Evan) G. Kulsveen, a Norwegian immigrant. In 1844, the couple bought the distillery property and renamed the company as the Kentucky Bourbon Distillers (KBG). At first the KBD produced whiskey from barrels that the Willett distillery had produced earlier. Then the Kulsveens increasingly began to purchase its whiskey by the barrel from other distilleries and bottle it under the Willet name, as on the bourbon bottle shown here. They were succeeded by their son, E.A. “Drew” Kulsveen, and his wife Janelle, to be joined by their daughter Britt Kulsveen and her husband Hunter Chavanne. All four today play a role in company operations. Thus, although the names have changed, the Willett blood and heritage is still present after almost 200 years over three centuries in the Kentucky whiskey trade.

In 1972 Martha married Even (pronounced Evan) G. Kulsveen, a Norwegian immigrant. In 1844, the couple bought the distillery property and renamed the company as the Kentucky Bourbon Distillers (KBG). At first the KBD produced whiskey from barrels that the Willett distillery had produced earlier. Then the Kulsveens increasingly began to purchase its whiskey by the barrel from other distilleries and bottle it under the Willet name, as on the bourbon bottle shown here. They were succeeded by their son, E.A. “Drew” Kulsveen, and his wife Janelle, to be joined by their daughter Britt Kulsveen and her husband Hunter Chavanne. All four today play a role in company operations. Thus, although the names have changed, the Willett blood and heritage is still present after almost 200 years over three centuries in the Kentucky whiskey trade.

|

| The Distillery Today |

Notes: This post was assembled from two major sources, the current Willett distillery website, www.kentuckybourbonwhiskey.com, and a post on the www.whiskeyuniv.com site, supplemented by additional information provided through ancestry.com. The combination of these resources made it possible to trace this significant distilling family’s long history and provide photographs.

Shown here is a cartoon of an inebriated gentleman attempting to pour himself a drink and missing the glass, much to the dismay of the bartender. Note the sponsor of this trade card. The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. is scolding the saloon for this unfortunate result because it is not using A&P’s “celebrated teas and coffees.” This is not a prohibitionist message against liquor, but rather a plug for keeping a teapot on the bar.

Shown here is a cartoon of an inebriated gentleman attempting to pour himself a drink and missing the glass, much to the dismay of the bartender. Note the sponsor of this trade card. The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. is scolding the saloon for this unfortunate result because it is not using A&P’s “celebrated teas and coffees.” This is not a prohibitionist message against liquor, but rather a plug for keeping a teapot on the bar.