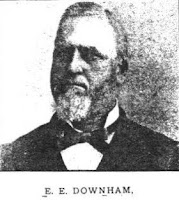

Alexandria was a Virginia town with strong Confederate sympathies that greatly resented Union occupation during the Civil War. That animosity failed to deter a New Jersey lad of 23 who arrived in 1862 to sell whiskey to thirsty troops. Despite this problematic start, he became Alexandria’s mayor and a leading citizen while founding a liquor business that prospered until the advent of Prohibition. His name was Emanuel Ethelbert (he much preferred “E.E.”) Downham, seen here in maturity.

Alexandria was a Virginia town with strong Confederate sympathies that greatly resented Union occupation during the Civil War. That animosity failed to deter a New Jersey lad of 23 who arrived in 1862 to sell whiskey to thirsty troops. Despite this problematic start, he became Alexandria’s mayor and a leading citizen while founding a liquor business that prospered until the advent of Prohibition. His name was Emanuel Ethelbert (he much preferred “E.E.”) Downham, seen here in maturity. Census records indicate that a substantial number of Downhams were in the liquor business and his father likely was among them. Certainly E.E. Downham, born in 1839, was versed in the whiskey trade when he arrived in Alexandria to set up shop amidst Yankee-hating Southern sympathizers.

E.E.’s promise as an “up-and-comer” must have been evident very early. In 1865, despite being a Northerner, he married Sarah Miranda Price, the daughter of a leading Alexandria merchant. The ceremony took place at the mansion of the bride’s father. The couple would be married for 56 years and produce four sons and a daughter.

Downham’s early business locations were on the lower end of Alexandria’s King Street. Whether he truly was a distiller, making whiskey directly from grain on his premises, is open to question. More likely he was a “rectifier,” someone who bought raw whiskey or grain alcohol from others, refined it, mixed it to taste, added color and flavor, bottled and labeled it. The resulting liquor was sold at both wholesale and retail. E.E. and his early partner, Henry Green, also dealt in beer and wine.

In 1867, in the wake of the Civil War, the Alexandria City Council, seeking to raise additional revenues, put a series of taxes on alcoholic beverages imported into the City from outside the state, thus discriminating in favor of Virginia-made products. When the young upstart Downham refused to pay the tax, the Alexandria City Council sued him and won. He appealed lower court decisions all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. At issue was an early test of the Interstate Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

While the Court refused on a technicality to rule in favor of Downham, it asserted its right to hear the case, disputed by Alexandria, and claimed jurisdiction to overturn local taxes that violated the Commerce Clause. As a result Downham v. Alexandria (1869) became an important legal precedent, frequently cited in cases up to the present day.

In 1874 Downham sought and won election from Alexandria’s Third Ward to the same City Council he had sued seven years earlier. He served there for two terms before seeking office on the Board of Aldermen and was elected there for five two-year terms. Following the sudden death of Alexandria’s mayor by heart attack at Christmas 1887, the Board met to select an interim mayor from among their number. On the sixth ballot, Downham was chosen. He was reelected in his own right in 1890, serving a total of four years, and then permanently retired from public office.

Throughout this period Downham continued his business in downtown Alexandria, beginning at 9 King Street and by 1881 moving to 13 King Street. Shown here is an 1885 ad with the latter address from E.E. Downham & Co. Wholesale Liquor Dealers. Four years later the firm moved to 107 King, It featured a menu of whiskey brands, among them was “Old Mansion.” It used an illustration of Mount Vernon on the label, on back-of-the-bar decanters, and on shot glasses, as shown here front and back.

Throughout this period Downham continued his business in downtown Alexandria, beginning at 9 King Street and by 1881 moving to 13 King Street. Shown here is an 1885 ad with the latter address from E.E. Downham & Co. Wholesale Liquor Dealers. Four years later the firm moved to 107 King, It featured a menu of whiskey brands, among them was “Old Mansion.” It used an illustration of Mount Vernon on the label, on back-of-the-bar decanters, and on shot glasses, as shown here front and back.

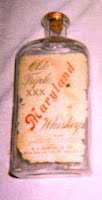

Other Downham brands were “Old Dominion Family Rye,” “Crystal Maize-Straight,” “Old King Corn,” ”“Mountain Corn” and “Old Triple XXX Maryland Whiskey” The flagship brand was “Belle Haven Rye,” with a well-designed label featuring heads of grain.

Shown here is a giveaway corkscrew with the slogan, “Pull for Downham Whiskey,” The instrument also cited prices. The cheapest drink was Old King Corn at $2 a gallon. Mountain Corn was $2.50 and Crystal Maize, $3.50 a gallon. Old Mansion sold for $1 a quart or $11 for a case of 12. Downham promised to pay the freight on any order over $2.50.

Other Downham brands were “Old Dominion Family Rye,” “Crystal Maize-Straight,” “Old King Corn,” ”“Mountain Corn” and “Old Triple XXX Maryland Whiskey” The flagship brand was “Belle Haven Rye,” with a well-designed label featuring heads of grain.

Shown here is a giveaway corkscrew with the slogan, “Pull for Downham Whiskey,” The instrument also cited prices. The cheapest drink was Old King Corn at $2 a gallon. Mountain Corn was $2.50 and Crystal Maize, $3.50 a gallon. Old Mansion sold for $1 a quart or $11 for a case of 12. Downham promised to pay the freight on any order over $2.50. The whiskey business proved lucrative and Downham moved his family into a home at 411 Washington Street, the city’s most fashionable. It was a double house and he appears to have owned both sides. His residence, shown here, is the one with the white door.

With time, E.E. Downham brought sons Robert and Henry into the business as he progressively became involved in other activities. In 1899, for example, he was active in a scheme to honor George Washington in Alexandria with a giant equestrian statue. The project required raising money around the entire United States. Citizens elsewhere apparently were not convinced of its need and the statue was never built.

By 1915 E.E. Downham’s principal occupation was president of the German Co-Operative Building Association, a building and loan organization at 615 King Street.

The whiskey business proved lucrative and Downham moved his family into a home at 411 Washington Street, the city’s most fashionable. It was a double house and he appears to have owned both sides. His residence, shown here, is the one with the white door.

With time, E.E. Downham brought sons Robert and Henry into the business as he progressively became involved in other activities. In 1899, for example, he was active in a scheme to honor George Washington in Alexandria with a giant equestrian statue. The project required raising money around the entire United States. Citizens elsewhere apparently were not convinced of its need and the statue was never built.

By 1915 E.E. Downham’s principal occupation was president of the German Co-Operative Building Association, a building and loan organization at 615 King Street. In 1917, despite his German connections, he was chosen as one of three Alexandrians serving on the local draft board for World War I. Meanwhile, with E.E.’s financial backing, son Robert bought the Lee-Fendall mansion, the birthplace of Confederate General Lee which still stands as a major Alexandria tourist attraction. The sons by now were responsible for the daily operations of the liquor business. By 1915 they had moved the company to 1229 King Street.

In 1920 National Prohibition closed down E.E. Downham & Co. forever. Downham himself died a year later at his Washington Street home, age 82. His obituary in the Alexandria newspaper stated that his “long life of usefulness entitled him to the esteem and affection” of all Alexandria citizens.