Mollyann avowed that because of the quality of his whiskey, Grandpa Sam while still in his twenties had become a favorite of the last German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, who had declared him “Baron Samuel Von Altschul.”

Mollyann had other amazing details. Shortly after receiving his title, the old lady said, Sam heard that a young woman in Piqua, Ohio, bore a birthmark that heralded the coming of the Jewish Messiah. With that information, he renounced his barony and left Germany for the United States discarding the “Von” along the way. He courted and married the lady with the purported birthmark, and started once again making the Kaiser’s favorite whiskey -- but now in Springfield, Ohio. All this was duly reported to the public.

A fascinating story, but was it true? The historical record suggests something else. Altschul Distilling claimed an origin in 1862, several years before Sam was born. The business was founded by his father, Samuel Altschul Sr., an immigrant from Germany.The date of Sam’’s birth varies by census but records show definitively that by 1881 he was a clerk in his father’s whiskey business. In 1890 Sam married Carolyn (Carrie) Lebolt of Piqua. Where Carrie bore the fabled birthmark on her person has not come to light, nor has the shape or character of the sign. Settling down to the life of a distiller’s wife, Carrie bore Sam four children: Charles, Justine, and fraternal twins Leon and Malcolm.

In the early 1880’s, perhaps upon the retirement or death of his father, Sam took over the Altschul distillery. At that time the business was located at 22 S. Market Street. In 1884 Sam moved to fancier quarters in Kelly’s Arcade, a relatively new Springfield retail center and hotel, shown above on a 1920 postcard. Altschul’s address was 62-64 Kelly’s Arcade for the next 23 years.

Although diminutive in size, Sam proved to be a giant as a marketer for his whiskey. In the late 1800s he began to advertise his liquors extensively in national magazines. His ads stressed: “One profit: From producer direct to consumer.”

Within a fairly short time, Sam had built a thriving mail order business. Altschul assured customers that he would ship his whiskey by express free of charge everywhere in the United States except the Far West.

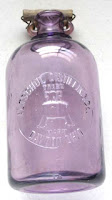

With success and the desire to be closer to his customer base, Sam moved his sales offices in 1908 to Dayton while maintaining his distilling operations in Springfield. As a result Altschul’s artifacts may have either or both cities named on them. As shown here, the distillery packaged its goods in both stenciled ceramic jugs and glass containers embossed with the name of the firm.

Within a fairly short time, Sam had built a thriving mail order business. Altschul assured customers that he would ship his whiskey by express free of charge everywhere in the United States except the Far West.

With success and the desire to be closer to his customer base, Sam moved his sales offices in 1908 to Dayton while maintaining his distilling operations in Springfield. As a result Altschul’s artifacts may have either or both cities named on them. As shown here, the distillery packaged its goods in both stenciled ceramic jugs and glass containers embossed with the name of the firm.  Sam featured more than a dozen brands, including: Altschul’s Bouquet Old Rye, Altschul’s Private Brand, Harvest Home Rye, Jolly Tar Rye, National Club Bourbon, Old Anchor Gin, Old Judge White Wheat, Old Private Stock Blue Ribbon X X X X, Silver Edge Rye, Springfield White Wheat, Staghead Rye, Sweet Home Rye, Sweet Clover Whiskey, Altschul’s White Corn and Teutonia Doppel Kummel. His flagship label was Old School Rye. He styled this whiskey “pure and potent.” He packaged his whiskeys in both ceramic and glass.

Sam featured more than a dozen brands, including: Altschul’s Bouquet Old Rye, Altschul’s Private Brand, Harvest Home Rye, Jolly Tar Rye, National Club Bourbon, Old Anchor Gin, Old Judge White Wheat, Old Private Stock Blue Ribbon X X X X, Silver Edge Rye, Springfield White Wheat, Staghead Rye, Sweet Home Rye, Sweet Clover Whiskey, Altschul’s White Corn and Teutonia Doppel Kummel. His flagship label was Old School Rye. He styled this whiskey “pure and potent.” He packaged his whiskeys in both ceramic and glass.

Sam loved to give away shot glasses. Several variations of Altschul shots exist for Old School Rye. They were designed by the most famous etcher of spirits glasses in America, George Troug. Troug’s sketchbook, shown here, contained a drawing for Old School Rye. Lagonda Club featured its own distinctive etched glass.

Sam loved to give away shot glasses. Several variations of Altschul shots exist for Old School Rye. They were designed by the most famous etcher of spirits glasses in America, George Troug. Troug’s sketchbook, shown here, contained a drawing for Old School Rye. Lagonda Club featured its own distinctive etched glass. About 1910, Altschul moved his operation from Kelly’s Arcade to 9 W. Main Street in Springfield. Son Malcolm joined him in the company. Unlike other Ohio whiskey outfits that went out of business when the state voted dry in 1916, Sam was able to operate until 1919, probably on the basis of his mail order trade to states that still permitted alcohol.

When National Prohibition arrived, Sam shut the door on Altschul Distilling Company and went into the real estate and insurance business.

He and Carrie were recognized as notable citizens of Springfield. He helped found a local newspaper; she was a leader of the Red Cross. According to census records, the couple resided in Springfield until at least 1930. Sam lived until 1939, dying in St. Petersburg, Florida. His body was brought back to Springfield and is interred there in Ferncliff Cemetery.

What about the story Altschul’s granddaughter told? My research indicates that German barons were titled through heredity, not by an action of the Kaiser. Nor can I find anything in the literature about a birthmark that heralds the coming of the Jewish Messiah. Mollyann’s account gives every evidence of being the kind of story a grandfather might tell a gullible youngster. From his genius at merchandising it is clear that Small Sam had a rich imagination. And, we can believe, a taste for tall tales.

No comments:

Post a Comment