On a rainy, chilly day in December in the late 1850s, a San Francisco saloonkeeper named Amandus Fenkhausen looked out at the dismal scene on Kearney Street outside his saloon. He called his wife to the front window. The roadway was a rutted, muddy mess and the buildings along it were surrounded by mud and pools of standing water as the rain pelted down. It was a sorry and depressing sight.

Amandus and Wilhemina had come across the Western plains with their first child to California together with other early settlers, among whom were many of their German countrymen. As a recent account put it, the Fenkhausens had embarked on a new life “in the desert of sand dunes that later was to become San Francisco. They had high hopes and strong in their hearts was the love of the fireside.” Recalling how the Christmas was so festively celebrated in their former home in Hamburg, Germany, the couple began reciting the many traditions that surrounded the holiday. Among them were the Christmas tree or as the Germans sing it: “O Tannenbaum”

Spurred to action by these remembrances of childhood, the Fenkhausen set to work. Fetching small branches of fir that had been destined for the fireplace, they fashioned a small Christmas tree and decorated it with ornaments they had brought from the Old Country. They set candles on it and placed the illuminated tree in the show window of their liquor store. As a result Fenkhausen, an immigrant wine and whiskey dealer, and his wife, are accounted as the first to introduce the custom of the Christmas tree to San Francisco. Today hundreds of lighted trees are a local tradition that draw thousands of tourists to the California city each holiday season. The Fenkhausens clearly started something.

But Amadeus must be remembered for more than his Christmas tree. He was among San Francisco's most successful whiskey men, a gent who left behind many colorful reminders of his enterprise. Born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1925, Fenkhausen had married the sweetheart of his youth, Wilhelmina, the daughter of a liquor dealer named Johann Frisch. Bringing along their first child, Caesar, the couple had come to America sometime in the early to mid-1850s, making the arduous overland trip to the West. The 1860 census found the family living in the Second District of San Francisco. The Fenkhausen family now included a daughter, Camina, and a second son, Rudolph. A third son, Walter, later would be born. Amandus gave his occupation to the census taker as “wine merchant.”

Fenkhausen’s saloon apparently was a successful enterprise and about 1861, according to one author, he established a wholesale liquor business at 322 Montgomery Street. With success, by 1865 when his enterprise first showed up in city directories, he had moved to 809 Montgomery, between Jackson and Pacific. He was billing himself as an “Importer and Wholesale Dealer in Wines and Liquors.” He also advertised as the local “depot” for “Star of the Union Stomach Bitters,” sold in an amber bottle with an embossed star. His whiskey bottles showed a bear, as at left.

Within two years he had relocated again to the northwest corner of Sansome & Jackson Streets. He used the occasion for an 1867 ad announcing that he “Respectfully informs his numerous friends that he has removed from No. 609 Montgomery street to the more convenient and larger building.” After remaining at that address for about three years, he took on C. P. Gerichten as a partner in 1869. Subsequently known as Fenkhausen & Gerichten, the firm moved to 221 California Street, doing business at that location until 1874 when the partners sold the business. Before long, however, Amandus was back selling whiskey, his liquor house now located on the northwest corner of Front and Sacramento.

Throughout all these changes of address and ownership, the clear implication is that Fenkhausen was the top dog. Unlike many other whiskey wholesalers, he featured only a small number of liquors in his inventory, many of them whiskeys that he was blending and compounding on his premises and attaching his own labels. Among his brands were A.A.A. Eureka,” Gold Drop XXX,” “Tennessee White Rye” and “Old Pioneer Whiskey.”The latter two were his flagship brands.

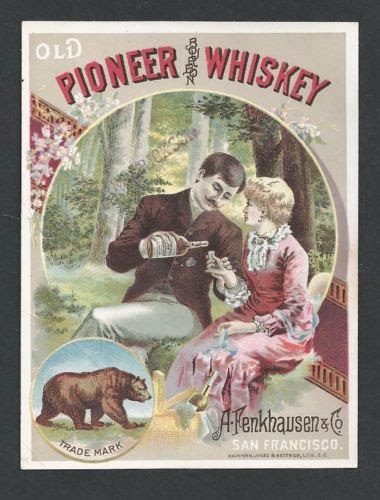

Throughout all these changes of address and ownership, the clear implication is that Fenkhausen was the top dog. Unlike many other whiskey wholesalers, he featured only a small number of liquors in his inventory, many of them whiskeys that he was blending and compounding on his premises and attaching his own labels. Among his brands were A.A.A. Eureka,” Gold Drop XXX,” “Tennessee White Rye” and “Old Pioneer Whiskey.”The latter two were his flagship brands. Fenkhausen advertised both vigorously. One of his ads for Old Pioneer Whiskey sparked some controversy when it appeared on a chromolithographed trade card. Shown here, it depicted a young dandy pouring out a glass of whiskey for an adoring young woman in a wooded scene. It gave the impression that an assignation of some kind might be in the offing. Even in rowdy San Francisco the image to some seemed risqué. Other Fenkhausen trade cards were more discrete, including one of a girl dancing with a shorter boy. (But they do seem a bit close together for the pre-pubescence set.) Note that both cards have the company trademark California grizzly bear.

Fenkhausen advertised both vigorously. One of his ads for Old Pioneer Whiskey sparked some controversy when it appeared on a chromolithographed trade card. Shown here, it depicted a young dandy pouring out a glass of whiskey for an adoring young woman in a wooded scene. It gave the impression that an assignation of some kind might be in the offing. Even in rowdy San Francisco the image to some seemed risqué. Other Fenkhausen trade cards were more discrete, including one of a girl dancing with a shorter boy. (But they do seem a bit close together for the pre-pubescence set.) Note that both cards have the company trademark California grizzly bear.

The company’s Tennessee White Rye Whiskey ads featured a comely young woman dressed in a Spanish shawl and carrying a fan. This image appeared on trade cards and in Fenkhausen’s ads. His pitch for this whiskey was its medicinal value. The ad shown here calls it a tonic “recommended by physicians.” A similar ad from 1886 goes into detail about Tennessee White Rye describing it as: “A pleasant beverage recommended by Physicians as a pure and healthybeverage, free from all injurious substance.” The same ad noted helpfully, however, that the whiskey was for sale in all “first-class” saloons as well as with druggists To make sure those saloon owners would use his liquor, Fenkhausen provided them with mirrored sign that trumpeted the brand.

The company’s Tennessee White Rye Whiskey ads featured a comely young woman dressed in a Spanish shawl and carrying a fan. This image appeared on trade cards and in Fenkhausen’s ads. His pitch for this whiskey was its medicinal value. The ad shown here calls it a tonic “recommended by physicians.” A similar ad from 1886 goes into detail about Tennessee White Rye describing it as: “A pleasant beverage recommended by Physicians as a pure and healthybeverage, free from all injurious substance.” The same ad noted helpfully, however, that the whiskey was for sale in all “first-class” saloons as well as with druggists To make sure those saloon owners would use his liquor, Fenkhausen provided them with mirrored sign that trumpeted the brand.

By 1879, Amadeus had taken on another partner, Herman Braunschweiger, and once again the business name was changed to reflect addition. The change occasioned still another move, this time to 414 Front Street where an 1880 San Francisco business directory found the partners. Son Rudolph Fenkhausen now was working in the firm as a bookkeeper. He resided at home with his parents at 1123 Sutter. Also living with them was Caesar Fenkhausen, listed as a clerk for Abrams & Carroll, a wholesale grocer.

In 1882, Braunschweiger struck out on his own and the business name reverted to A. Fenkhausen & Company. For the next four years Amadeus ran his liquor operation alone, bringing Rudolph into its management. His health declined, however, and in March 1886, Amandus died, age only 62. While his family grieved by his graveside, he was interred in the Laurel Hill Cemetery, shown here. The cemetery was one of San Francisco’s oldest, known for its prestigious burials, including civic and military leaders, inventors, artists, and eleven U.S. senators. And, we can add, at least one notable whiskey man.

Rudolph took over the operation of the A. Fenkhausen & Co., moving the business one last time in 1892 to 705 Front Street. Two years later the company Amadeus had built disappeared from local directories. It was followed in 1895, however, by a new liquor business at 5-7 Drumm named R. Fenkhausen & Co. My supposition is that this establishment was Rudolph striking out on his own. It appears to have been very short-lived.

The end of the Fenkhausen name on liquor establishments in San Francisco, however, cannot erase from local memory that soggy pre-Christmas day when Amadeus and Amanda Fenkhausen put the their hand-fashioned Christmas tree in the window of their saloon to light up the dark night. The Fenkhausens clearly knew how to keep Christmas and spread its joy to others. Wrote one newspaper: “Passersby stopped, stared and gathered to celebrate. The tree brought cheer to all lonely men far from home.”

.jpg-%2Br.jpg)